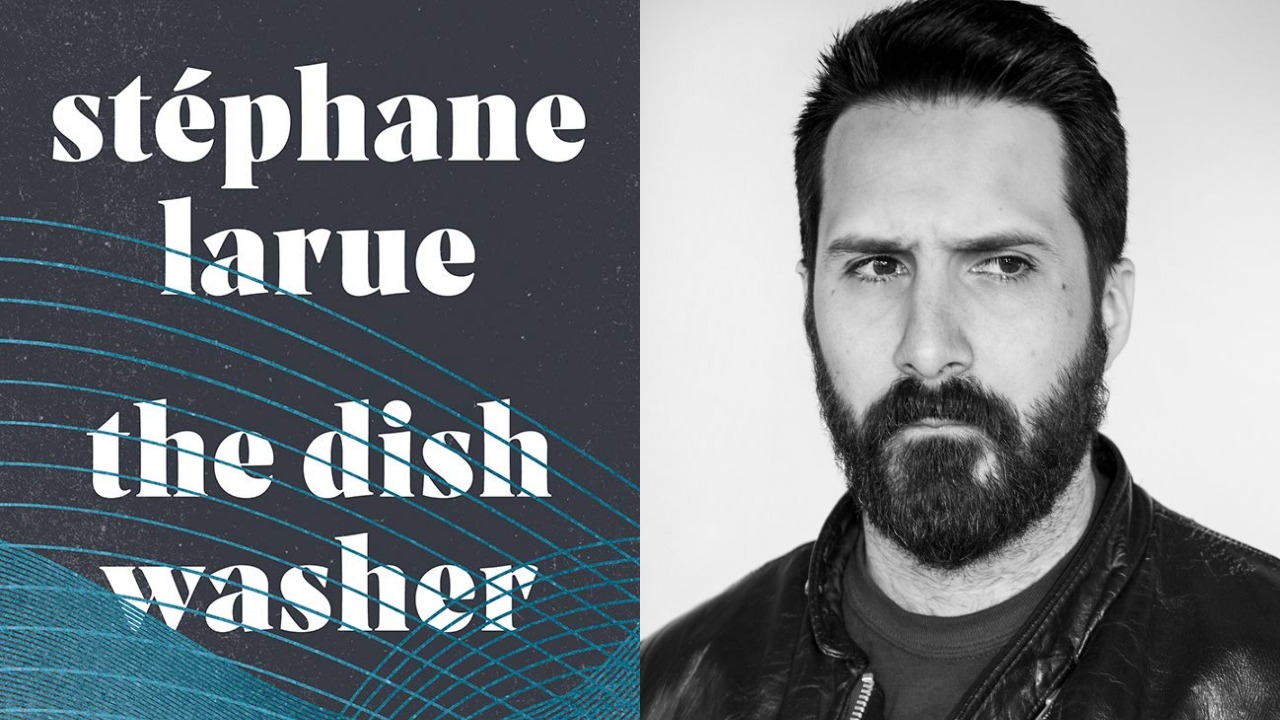

The Dishwasher: An interview with Stéphane Larue

Over the years, Stéphane Larue has held countless jobs inside Montreal’s high-end restaurants: dishwasher, busboy, server, manager. His first book takes readers behind the scenes into the chaos of the kitchen environment. Set in the early 2000s, The Dishwasher follows a young, unnamed narrator navigating the stresses of Montreal’s fine-dining industry while managing a gambling addiction.

Originally published in French in 2016, Le Plongeur became a literary sensation in Quebec, winning the Prix des libraires du Québec and shortlisted for the Governor General's Literary Award for French-language fiction. The English translation, published last year by Biblioasis, has just been nominated for the Amazon Canada First Novel Award.

This interview has been translated from French, and condensed and edited for clarity.

Étienne Lajoie: In your writing, you describe Montreal in great detail. Considering that most readers probably don't know Montreal very well, do you think they’ll be able to appreciate your work?

Stéphane Larue: There’s something that emerges from this very literal, very realistic description of Montreal—not far from the way several writers have worked, like Henry Miller. It conveys a sense of metropolitan-ness, an urbanity that any city-dweller around the world will recognize.

ÉL: This inspiration—you mentioned the level of realism—where did it come from?

SL: The desire to go as far as possible in the realism around Montreal may have arrived somewhere around the second or third version of the manuscript. The more I talked to my publisher, the more he wanted me to go all-out on realism. To put pointers that weren’t just “easter eggs”—Montreal is a living organ with its bars, restaurants, shopping streets and neighbourhoods.

ÉL: There is also a certain texture in the novel, a feeling of being present in the kitchen and in the dish pit. How far did you delve into your own memories during your writing process?

SL: It's a bit funny because by the time I was a dishwasher…I didn’t know this yet, but it would come to serve as material for Le Plongeur. My first jobs are always something that have crystallized in my memory. There are colleagues who read the book when it came out—people I have known for fifteen years—who asked, “were you working or taking notes?” But it just stayed fresh in my memory. I still remember the smell of diving into the dish pit at Misto, where I worked.

ÉL: In a podcast with “Bob the Chef,” your former colleague, you explain how you always wanted to write a novel when you worked with him. Were you putting pressure on yourself at the time? What was your mental state about writing a book?

SL: By the time I met Bob, I was a dishwasher and I was writing stuff—my little life, parallel to the job, of making fanzines, going to reading parties. I was the kid who had writing aspirations but it seemed too big to be achievable. I thought I was a beginner. I still had a lot of craft to learn and books to read to get to the place where a writing project could be publishable, in my opinion.

ÉL: Being a “diver”—plongeur, in French—is a job where you spend a lot of time in your head, since you’re doing repetitive and manual work. Was that fertile ground, when you had aspirations to write a novel, to think of book ideas?

SL: Of course there are peaks where you’re really in the thick of it or you’re just thinking about your job, but there are occasions when you’re in your head. In the room where I worked, it was a little removed from the restaurant, so I was alone with my music and my ideas. I had a little notebook sometimes for writing stuff, but it was no big deal.

This time was an incubator; it’s a job that I appreciated because, in a way, these moments of reflection allowed me to cultivate the ideas that were running through my head.

ÉL: You talked in a few interviews about how the character was inspired by real-life experiences. Why did you wait until the very end to tell the reader that the character is named after you?

SL: Part of that is a purely narrative element. But in life, when we talk to each other, people don’t always use each other’s names. Sometimes you can spend weeks with your best friends without ever saying their names. Obviously, some of the material comes from my life, but there is a pact of solidarity with the people who inspired the book, there are people who gave me permission to describe their lives, which means that it became necessary to name the narrator. It’s like when your exasperated cousin says “Stéphane!” It's like when your parents nag you and call you by name to wake you up. It’s a narrative and authorial choice.

ÉL: The schedule of a kitchen is the opposite of the regular rhythm of life; you go back to work when the rest of the world leaves theirs. How did you write this novel? At what time of the day did you feel most comfortable writing?

SL: Writing Le Plongeur was a physical test. Many of my colleagues are restaurant lifers; I had an intellectual, writing life on the side, but working in a restaurant made it possible to fit that into my week because I was able to compress my shifts into a few days. In the first two weeks, I already had 120 pages. In the wake of the master's thesis that I was writing at the same time, I really got a writing rhythm that was Olympic. Anyone who works at night, with a few exceptions, will tell you that your brain no longer works the same.

ÉL: You’re talking about a physical test—in my head it’s also a bit like the reality of working in restaurants. It never stops. Do you think the book would have been different if you had written it in isolation, away from everything?

SL: Steven Koch, a creative writing teacher, explains that you are always going to have to organize writing in a certain way and it will always colour your writing. I am not a CEGEP professor who has his summers to be able to write. This book, I could not have written it otherwise and it reflects my occupation.

ÉL: I had the impression as I read that there was a certain vulnerability to the narrator. In English they say “bend but don’t break,” but in his case there’s a more lasting bending, a curve. To write that way, did you need to become vulnerable, mentally?

SL: I'm trying to recount my relationship to addiction, so I'm trying to tell it as accurately as possible and including all the fallout. When you have addiction problems, no matter which ones, often you’ll go through it in secret. And what does secrecy imply? It involves lying. And what does lying implicate? Friendships. I was trying to follow the natural thread of what this addiction causes in this narrator. I could have made someone who is obsessed with the pleasure he gets from his addiction: it would have made another complete novel. The kind of character I wanted to make was near me. You see through the novel that it’s really just a good little guy who made a couple of bad choices and who’s a little stuck.

ÉL: What did you learn about yourself while writing?

SL: I learned that I could write a book. It's something where you never know if it's going to happen. I realized that I may have things to say in the end. Literary material is everywhere.

ÉL: Are you wondering about your place in the world of Montreal restaurants? Didn't you think you had the license to write this novel?

SL: I thought to myself “who am I to have the right to speak about this environment,” but then that if you’re able to write, you have the right to speak. At the very beginning of writing, I refused to editorialize, unlike guys like Anthony Bourdain who always put his two cents. This is another kind of writing—it was more of the chronicle. I had refused to vent. There have been a lot of situations surrounding the promotion of the book, and there are a lot of things to which I said no because they wanted to make me into the token guy who is a restaurateur and writer.

ÉL: A book on the restaurant business, too, is not something that has been done in Quebec.

SL: Le Plongeur, yes it’s about the restaurant industry, but it’s also a novel about work, about money, about extremely material realities that everyone knows and shares. This is a topic that we do not often see in Quebec literature. There is nothing more dramatic than arriving at the thirty-first of the month and you don't have the money to pay your rent; it's a tragedy. These are problems that seem to be commonplace, but on the contrary, they are what creates dramatic and realistic tension.

Editor's note: As a pandemic summer begins, people are looking for books and music—while artists and musicians can't go on tour to publicize their new work. For the next week, Maisonneuve will publish daily online reviews of Canadian writing, music, art and cultural trends.