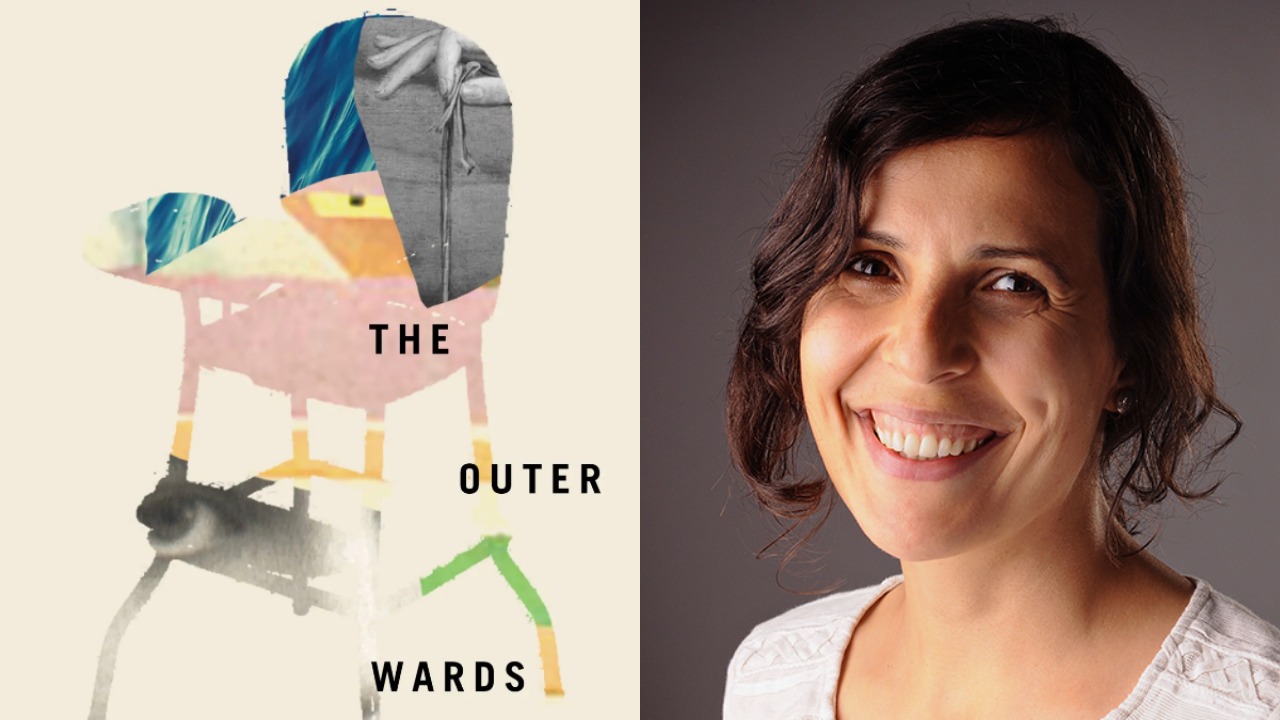

The Outer Wards: An interview with Sadiqa de Meijer

As the world grapples with huge questions all at once—how to tackle racism, whether the pandemic is sending women back out of the workforce—Canadians would do well to read Sadiqa de Meijer’s new collection of poetry.

Based in Ontario, de Meijer has roots in the Netherlands, Kenya, Pakistan and Afghanistan. She sprinkles her writing with Dutch words, working in her “own language,” and she equally refuses to shy away from pat solutions to other dilemmas.

The Outer Wards (Signal Editions/Véhicule Press), her second collection, examines with painful bluntness how a life-altering sickness can disrupt a mother’s obligations. De Meijer recounts the pain of not being able to care for a child. “And my girl wants to nurse / and I’m apologizing senselessly / for everything I ever haven’t done,” she writes in “Women Do This Every Day.”

De Meijier writes in various forms. Her debut book of essays about her mother tongue, alfabet / alphabet—which explores questions of identity, landscape, family and translation—is forthcoming this fall with Palimpsest Press.

Albina Retyunskikh: The first poem in your collection is called “On Origins.” What do you consider to be your origins, and where is home to you?

Sadiqa de Meijer: My origins are mixed, which represents to me a deep and lonely form of good luck. My father's ancestors came from Pakistan and Afghanistan to Kenya, a number of generations before his. One of them married a Maasai woman, so my father is mixed himself, which had its own consequences in his life. My mother is Dutch for as far back as I know. When I was a child, we lived mostly in the Netherlands—my birth country—but also in Kenya, and then we moved to Canada, which added a fourth continent to the picture.

Home is not a place to me, although there are Dutch cities and landscapes that feel as if they exist inside of me wherever I go. But also, when I’m in my workroom, I feel a sense of belonging that has no geographical bounds.

AR: Your poems shift between English and the occasional Dutch word, which you call “your own language” in the book. How does moving between languages, and your relationship to your mother tongue, shape your writing process?

SDM: This is something I've thought about a great deal in the last few years, culminating in the writing of a language memoir; it's called alfabet / alphabet and comes out in September with Palimpsest Press. My first language retains for me a sense of embodied identity and access to early memories that English has not been able to replace, even though I learned it early on and my fluency range is wider in it than in my mother tongue. I suspect that part of me, when writing, is trying to make English lines and phrases speak to my earlier selves; sometimes it’s by favouring Germanically rooted words, or through landscape or location, or through more mysterious processes of reworking the phrases until I can feel them.

AR: At one point in the collection, you refer to motherhood as "the submerged world." Can you tell me more about what you mean?

SDM: I was thinking in part of the experiential shift that the same poem also refers to: "I move differently now, which means I have altered / my temporal experience." The feeling of inhabiting an altered life rhythm that revolves around the needs of a small child or children. And sleep deprivation contributes to that. But the submerging is also into a less visible role; moving from an individual self to that of a generic (and not incidentally: unpaid, often socially unaccommodated—I've rarely seen a lecture or reading with child care!) mother figure.

AR: You’re tackling questions of maternal duty and mothering through sickness. Historically, there seems to have been a lot of silence around this subject, at least in terms of cultural representation. Why do you think that is?

SDM: Yes, you're right, I have found that as well. Part of the reason, I'm sure, is the historical sidelining of the subject of motherhood. Also, the experience of being seriously ill while mothering is overwhelming, especially for single mothers—so the privileges needed to write (lucidity, energy, privacy, time) are often not available. There is a sense, as well—although the mother is not guilty—of owning up to a failure. And then, of course, some of the inspirations for my poems were women who died of their illness. Part of the reason for this book, for me, was that I saw the possibility of reporting from a place where others had been, but had left silently. There are amazing exceptions, though. One book that deeply affected me is Genevieve Castree's A Bubble, which she wrote while terminally ill as comfort and record for her child. Or Sylvia Plath's poem "Nick and the Candlestick," in which I also read this theme in the mother's psychic pain contrasted with her child's unblemished nature.

AR: In “It’s the Inner Harbour neighbourhood, but everyone calls it Skeleton Park,” you write: “I’m Guatemalan, Native, Arabic, whatever, they insist they’ve met / my sister, but I have no sister. And the ones who say, / that’s so interesting, I’m just boring old nothing, are the most / dangerous people, who think they have no history.” In what ways does race influence your work and your life? What do you want these people who think they “have no history” to learn?

SDM: Racism is a big subject for me. As a mixed-race person who has lived almost my entire life in predominantly white countries, I know I unsettle people who use race to secure their own identity and order their world. I witness the arbitrariness, pervasiveness, and painful effects of what race means, both within myself and my community. I also deeply love people who are at higher risk than I am of racist actions. So being involved in anti-racism work, and examining its themes in my writing, are important to me.

My greatest teacher is James Baldwin. I would love his work no matter what the subject, because he writes so achingly well, but his insights on race have shaped my perspective and kept me sane. He is in this part of the poem: the idea that seeing your own white history as given and inevitable, and requiring no truthful examination, is in service to its perpetuation. I wish people who operate that way would understand that, just as there are intergenerational traumas, there are also intergenerational behaviours of oppression. That they are living them, and they see this as safety but really it's a suffocation, and it won't stop until they are willing to understand their ancestors.

AR: What influences and inspirations were you working with while writing these poems?

SDM: What I was consciously working with was a long-standing love for the work of Sylvia Plath and Elizabeth Bishop. I felt that the qualities of their voices were present, and in some tension, inside of me: Plath's raw and sonically driven approach, with its dramatic invocations of the mythical, against Bishop's measured reticence, and her fidelity to the observed details. Of course, the book has other influences as well—nursery rhymes, religious mythology, the works of writers Etty Hillesum and J.A. der Mouw, painter Jack Chambers, to name some.

AR: With the pandemic, so many people are being confronted with the ways in which illness can disrupt parental duty. What lessons or comforts do you hope these poems offer in this time?

SDM: I'm not sure I expected the poems to be of comfort—they were written almost as a witnessing of something painful—but I've been moved to hear from people that they do find solace in them. I believe the line "Tell me of your life without evasions" is an arrow towards an answer. To be seen and known, past our surface constructs of identity, is a longing in us, no matter what our life stage. And when we do make that moment of contact, within a relationship, it is atemporal in nature—meaning that it somehow holds its own within the pain of the losses, which are always losses of time with a person, the nature or the length of time you expected or imagined.