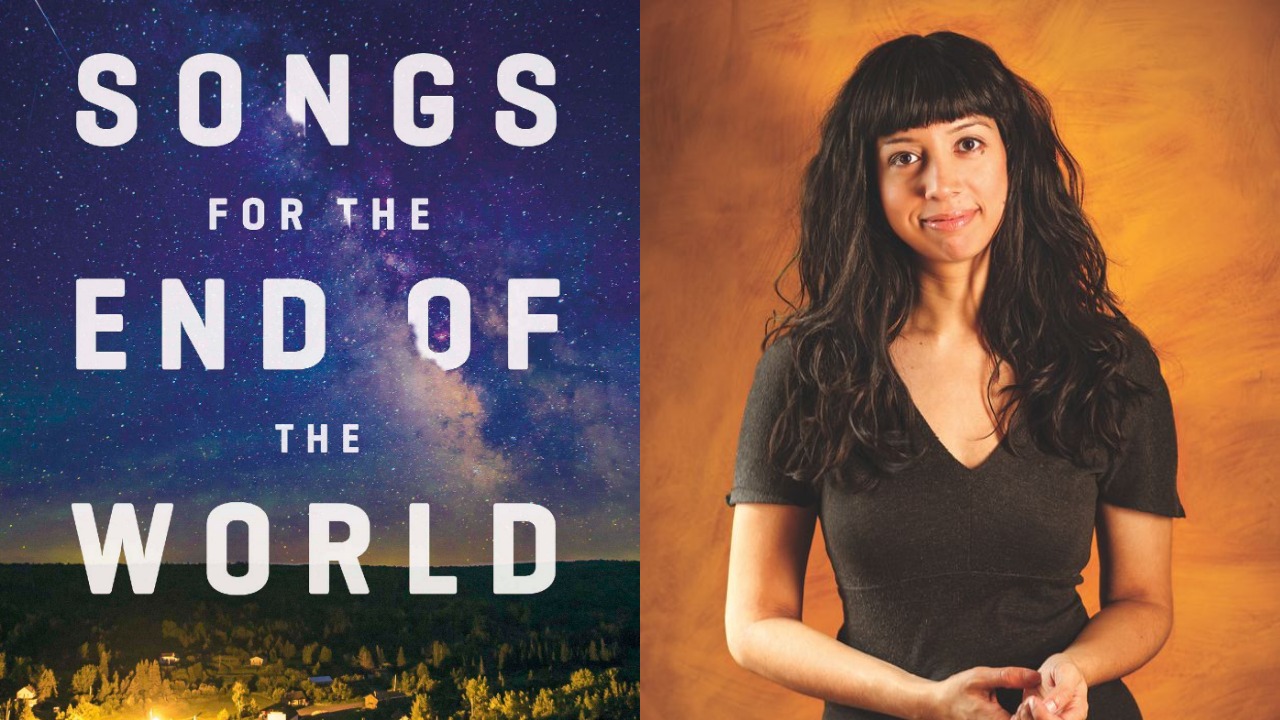

Songs for the End of the World: An interview with Saleema Nawaz

Saleema Nawaz didn’t want to be a prophet. When she began working on a pandemic-themed novel seven years ago, she was looking towards the past. She researched historical global disease outbreaks, including the Spanish Flu, Ebola and MERS-CoV. She dove into epidemiological research, intervention strategies and the ethical and legal considerations of preparing for a pandemic.

Nawaz took what she learned and crafted a work of fiction. And then, just months before her novel was set to be published, she found herself living in a reality that eerily paralleled the plot she had written.

Songs for the End of the World (McClelland & Stewart) spans twenty years, leading up to a pandemic supposedly unfolding in New York City during the summer of 2020. The narrative is filtered through seven diverging perspectives. The characters, most of whom are strangers to one another, are linked by a mysterious girl who is known to have been at the first site of infection.

Nawaz explores the importance of human connection and meditates on how we carry grief in unexpected times. She examines how we are bound to our loved ones and communities, raising questions about the world we are creating through our individual and collective actions.

This is the Montreal-based writer’s third novel. Originally planned for publication in August, an electronic version of the novel was released in April in response to the current crisis.

Lorenza Mezzapelle: Of course, Songs is particularly relevant right now. I don’t want to ask too many pandemic questions and risk sounding redundant. That being said, its release is incredibly timely. How does it feel to watch your book become a reality?

Saleema Nawaz: Well, I’ve sort of been running out of synonyms for the word surreal. It is really, incredibly surreal and it’s hard to believe it’s happening. I think it’s hard to believe it’s happening without having written a book, you know? And having written it, it’s just even more strange to look through.

LM: Despite the plot being centred around a pandemic, Songs explores many themes. Do you think of it as a pandemic story, a story of hope, a story of humanity, or something else entirely?

SN: For me, stories usually begin with the characters. But the idea of a pandemic connecting them all was something that was always right there from the beginning. So, I guess the whole time I’ve been working on it I have been calling it my plague novel, in shorthand. But the themes of hope and human connection, and the relationships between people, were what interested me the most in writing it. A crisis is a good way of testing relationships between characters. So it was an opportunity for showing how crisis not only it affects our day-to-day, but also our relationships with one another. Does the pandemic bring out the worst in people or the best in people? And what do we owe to one another, what is our responsibility to other people?

LM: Songs was originally set to be published later in the summer. After the spread of Covid-19, an electronic version was made available earlier. How did you anticipate it being received, had it been published if Covid weren’t a reality?

SN: I guess I will never know. I honestly am curious about that—I have no idea. It’s one of those things where you hope that your book will be judged on the quality of the writing, not how well it holds a mirror, or a crystal ball, I should say, up to reality. But I’m grateful that it is out and that it can be a part of the conversation now. I was just really really grateful that it could come out early because I had this lonely sense of having written something that, to me, really spoke to what we were going through and showed the kind of hope that we need right now and the kind of need for connection, and community, and cooperation above all, to get through this. At the very beginning, I was just kind of devastated that I was not going to be able to have this out there in the world at the time where I felt like it could make a contribution to people’s lives in any kind of positive way.

LM: The book feels like a symbol of hope and something that people can look to to make sense of the importance of connection. Is this very different from what you initially wanted readers to take away from it? Has your intention changed at all, and what are you hoping they will take away from it given the current crisis?

SN: It was absolutely what I had hoped. I wanted to write a novel about a pandemic that was realistic and which didn’t give in to those sort of sensationalistic tendencies of a post-apocalyptic world where there’s chaos, and society breaks down, and it’s everyone for themselves. My instincts really are that people, on the whole, when there’s a crisis, behave with goodwill and social responsibility. And research backs this up: disaster is a time that can bring out the best in people, and the shared experience of living through a disaster can bring us closer together as a society.

We have inherited all of these ideas from Hollywood and dystopian fiction about how people will behave, and what kind of model does this give us in a real crisis? In some sense, the novel is writing against that tradition, saying: here’s how I imagined it would really be and here are possible ways that we can behave. I hope that readers can connect to the novel, as a story, and to the characters that they meet on the page, and hopefully take away that message of hope.

LM: At one point, you illustrate the life of a family sailing across the globe at the turn of the century. They face isolation, the rapid rate at which technology is developing, and other problems they fear will arise in the year 2000. The two sisters and their mother often mention the loneliness they feel while being on a boat away from home, and away from their family and friends. Was it intentional to have this storyline parallel that of the other characters’ lives, who are experiencing the pandemic unfold in the present-day? Was it a way of exploring the notion of isolation in two separate ways?

SN: Absolutely. I think part of what the novel is exploring is this notion of, in a pandemic situation, you’re afraid of contagion… are other people the problem or are they part of the solution?

LM: The book is quite meta. As the narrative unfolds, Owen, a character who wrote a novel called How to Avoid the Plague, watches as his book becomes a reality. At times, he and other characters feel as though they cannot differentiate the real world from the fictional one. Do you ever find yourself identifying with these characters? Did you shape their experiences and actions based on how you, yourself, thought you might act in the given situation?

SN: I think there’s probably a part of me in all the characters. Certainly, at the beginning of the crisis, I was really identifying with Sarah, a mother who is worried about her son’s safety and the best way to protect him, and her general uncertainty about the best course of action. Owen is extremely paranoid and extremely self-protective. [Because of his extensive research on diseases, Owen takes extreme measures to avoid the outside world, including buying a boat to live in and keep away from the crowds in New York City.] I think I almost, in not wanting to be like him, kind of reacted against it in not going out and super preparing the way that he does.

Overall, I probably identified the most with Emma, a musician who wants to connect to other people through her art and through her writing. Fiction is always this kind of imaginative exercise, right? Like, what would I do in this scenario? Or, what would I do if I were this other kind of person?