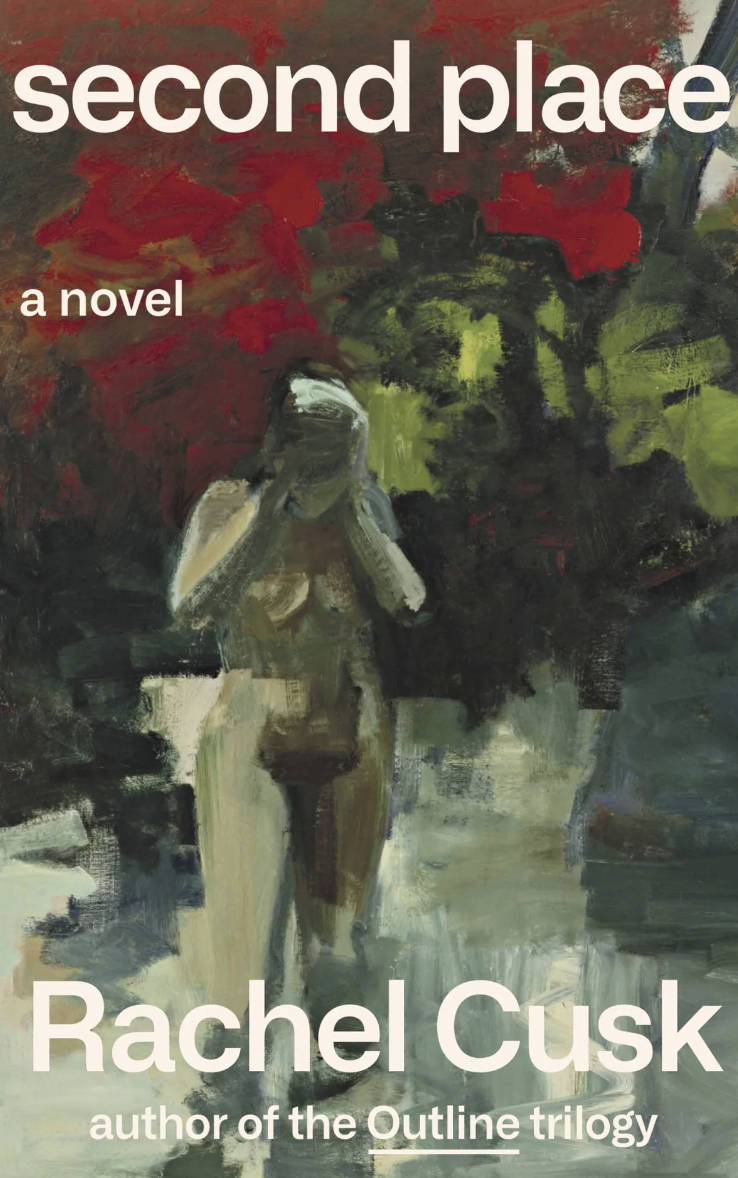

Second Place

In Rachel Cusk’s new novel, six characters are stuck on a misty marshland in some unspecified place. One of them is a painter, and that is why he was invited. Naturally, the gentleness of his artistry does not extend itself to his sense of social etiquette. He’s prone to hide away and work. Whenever he makes an appearance, he remains aloof. This frustrates the woman who invited the painter to the marsh, who feels as though they have some deep connection.

Second Place is about artists, patrons and the shifting balance of power between the two. The postscript tells us the book is a tribute to American patron of the arts’ Mabel Dodge Luhan’s 1932 epistolary memoir Lorenzo in Taos. Luhan’s memoir recounts her time playing patron to DH Lawrence with juicy, albeit disastrous, results. With details shuffled, Second Place progresses similarly. The story is told through the narrator’s letters to her off-stage friend, a poet named Jeffers.

Second Place is Rachel Cusk’s first work of fiction since she completed her Outline trilogy in 2018. The first of the trilogy was a novel marked by an “annihilated perspective,” she told The Guardian. She’d “lost all interest in having a self.” This disinterest stemmed from the backlash to her second memoir, 2012’s Aftermath: On Marriage and Separation. A chronicle of her divorce, many critics found Aftermath revealing to the point of being indecent (or philosophical to the point of abstraction, depending on who you asked). Critical response nearly destroyed Cusk, leaving her unable to write for some years. She returned, determined to write without leaving any trace of herself on the page.

In the Outline series, Cusk introduced readers to Faye, a practically invisible narrator (her name only comes up once in each of the trilogy’s books). Throughout the trilogy, Faye plays listener to a lengthy cast of interlocutors who present themselves to her on planes and boats, or at literary conferences and hair salons, before vanishing. These strangers share a love for the implausibly long monologue beloved by writers; if Faye engages with them, it is often only to question something said.

In Second Place, Cusk leaves behind the circumspect vantage point of Faye. Instead, we meet M, whose naivete sets the story in motion. M is a middle-aged woman living on a marsh, the “vast wooly breast of some god or animal,” as she describes it, with her second husband, Tony. M and Tony have met each other later in life; set in their ways, their marriage is less a tangled union and more a “meeting of two distinctly formed things, a kind of bumping into one another …” M broods, spends her days thinking. Tony is practical, reliable; he has spent much of his life on the property and tends to the land. M is the kite, Tony the string.

On their quiet property lies a small cabin, referred to as “the second place.” The second place has come to function as an artist’s residency, and a sort of pressure relief valve for M’s creative drives. (M is a writer, but we only find out late in the story, as if to say that her roles as wife, mother, woman all come first). For years, M, quite thirstily, has tried to get L to visit the second place. He has rebuffed previous invitations. This aloofness only portends what is to come from him, and it is also that same aloofness, M feels, that makes his work so exhilarating.

L’s portraits are aesthetically liberated, “objective and compassionless”; another way of saying “male down to the last brushstroke.” (Womanhood in Cusk’s work has often been a fight against the foreclosure of possibilities and creative freedom—or the acceptance of it.) Years before, L’s paintings had inspired M to finally leave her first husband. Even in the marshlands, she can still look at his paintings and feel what she first felt. “I saw … that I was alone, and saw the gift and burden of that state, which had never truly been revealed to me before.”

M makes the rookie mistake of conflating the art with the artist. Feeling seen by art doesn’t mean the artist sees you. Just as Faye told one of her writing students in the Outline trilogy’s mid-section: “It was perfectly possible to become the prisoner of the artist’s vision.” Nevertheless, M thinks hosting L in the second place will inspire in her the same critical distance that his work did all those years ago, and allow her to examine life anew. M is frustrated with the mundanity of life; reality, to her, is only interesting insofar as it is portrayed through art. Were L to come and paint the marsh, as she suggests in her invitation, she might see what it looks like through his eyes.

L wants something in return. He hasn’t just come around to finally accepting her invitation because he thinks it could be fun. He needs somewhere to weather the storm, as a global catastrophe has put the world, and the global art market, on hold. Informing M of his unexpected imminent arrival, he writes, “I’ve gone tits up.” He’s lost his house, or perhaps bled other people’s goodwill dry. “All my value wiped off everything like a layer of scum.” He arrives with an unexpected companion in tow—a younger woman named Brett who is carefree in the way only the immensely wealthy seem to be. (Brett arranged for her and L to arrive in a relative’s private plane.)

This probably isn’t the Covid novel readers have been dreading (many good novelists have been lost to the brainworms of the Trump-era; we don’t need to lose any to Covid-19). The time period, like the location, is nebulous. There are few mentions of any modern-day technology that might situate the story in the present; M’s frequent poetic apostrophes and exclamation marks (“Oh, it wasn’t at all how I’d planned it!”) give her reflections the flare of interwar modernism. This may be deliberate: one of the story’s conceits—that it draws inspiration from a 1930s memoir—suggests a desire to remain vague on the matter. Aside from a handful of mentions of a collapsing art market and “global pandemonium,” the world outside of the marsh has little bearing upon the story.

M interprets L’s decision to spring another guest upon them as a tactical choice. Not only does the presence of another guest require them to yield personal boundaries, thereby giving L an edge over them, M also suspects that Brett is there to shield L from her attention. M might be wrong, and L could just be so inconsiderate that it seems strategic. Either position produces tangible discomfort for M, who is quick to treat L as though they have a strong connection. She reads his indifference as strange, when he may just be a stranger whose malevolence only grows.

For all M wants from L, though, she is not completely without. She is a patron in a world where artists are at the patron’s mercy. Cusk doesn’t forget that power dynamics—part of our nomenclature du jour but often flimsily deployed—are, as stated, dynamic, not static; the balance is unstable. M has an expansive property and the means to be generous with it (generosity being “a form of control,” she admits). L, meanwhile, has the artistic gifts—“lamp-like eyes”—and an indifference to the world that she feels is inaccessible to her as a woman.

L and Brett’s arrival coincides with that of Justine, M’s daughter from her previous marriage, and her boyfriend Kurt. Kurt is a preppy who speaks in cultivated vowels, wholly unfit for country life. Kurt first flanks Tony with “childlike attachment” and he starts to glory in the “handiness and practicality” that Tony’s novice chores instill in him. Kurt quickly abandons Tony to bask in the company of L; not long after, he fancies himself a writer, seemingly inspired by L.

Kurt’s decision to take up “matters of a higher order” requires others to commute to town to pick up reams of paper. He dons pens in the pocket of his dandy-ish robe. M observes him “reproaching us all for our triviality and wasted time.” If this sounds like the makings of a high British comedy, wait until Kurt reads his work-in-progress over the fire: “It was set in an alternate world … with dragons and monsters and armies of imaginary creatures interminably fighting one another, and great lists of names like in parts of the Old Testament, and pages of oracular sounding dialogue which Kurt spoke out very slowly and solemnly.”

One wouldn’t be at fault to wonder about Kurt’s high-fantasy epic segueing into something like the book we are reading. Second Place, after all, has an intriguing and uncharacteristically phantasmagoric cold-open (M sees the devil on a train; returning to a decidedly more conventional form of novel-writing than that of the Outline trilogy, it appears someone has told Cusk about foreshadowing). Doubtful. Kurt reads for hours. The fire out, everyone half-asleep, only L, the star by which Kurt chose to navigate his new course, offers any feedback: “Be careful what you ask people to endure,” he says, thereby ending their closeness. He could be speaking to M in that moment, too. Could her life, and the people in it, co-exist among the autonomy she so strongly desires?

Other moments of guests-from-hell comic absurdity appear throughout. Brett gently mocks M’s clothes, M explodes; M all but begs L to paint her after discovering he’s literally done a portrait of everyone else. These lively scenes contrast the claustrophobic philosophizing that dominates M’s letters to Jeffers and Cusk’s output in general. Unexpected as the elevated drama may be, the game of cat-and-mouse between M and L successfully dramatizes Cusk’s foremost concerns of women’s barriers to freedom, the meaning of art, good, evil, etc. The chaos amongst characters (people doing things in a book, who would have thought?) makes for a nice reprieve from the novel’s more cerebral passages.

In the book’s penultimate moment of humiliation, M rushes to the second place after L has finally agreed to paint her. She has put on her old wedding dress—the most close-fitting item she can wear. When she arrives, she finds Brett and L both high out of their minds and painting the walls floor to ceiling. There are “trees with great twisting intestinal roots … flowers fleshy and obscene, with big pink stamens like phalluses.” A Garden of Eden scene, M deduces, and in the centre, there she is, the Eve figure. They give her a big moustache—so everyone knows who is in charge. It is no spoiler to say that in this cloistered comedy of errors, the sadistic male artist winds up losing out. His art endures, though.

In the Eden of M’s marsh, art is the serpent. Soon after her humiliating discovery, M considers the possibility that the entire enterprise of art-making may itself be a serpent, “whispering in our ears, sapping away all our satisfaction and our belief in the things of the world” and mostly, our belief in people. M is unable to access L’s sort of freedom without her life falling apart—bleak, but this is how Cusk thinks. “Being a person has always meant getting blamed for it,” she told the New York Times. Such drama may make life challenging, as it surely has for Cusk. It makes books more exciting, though.