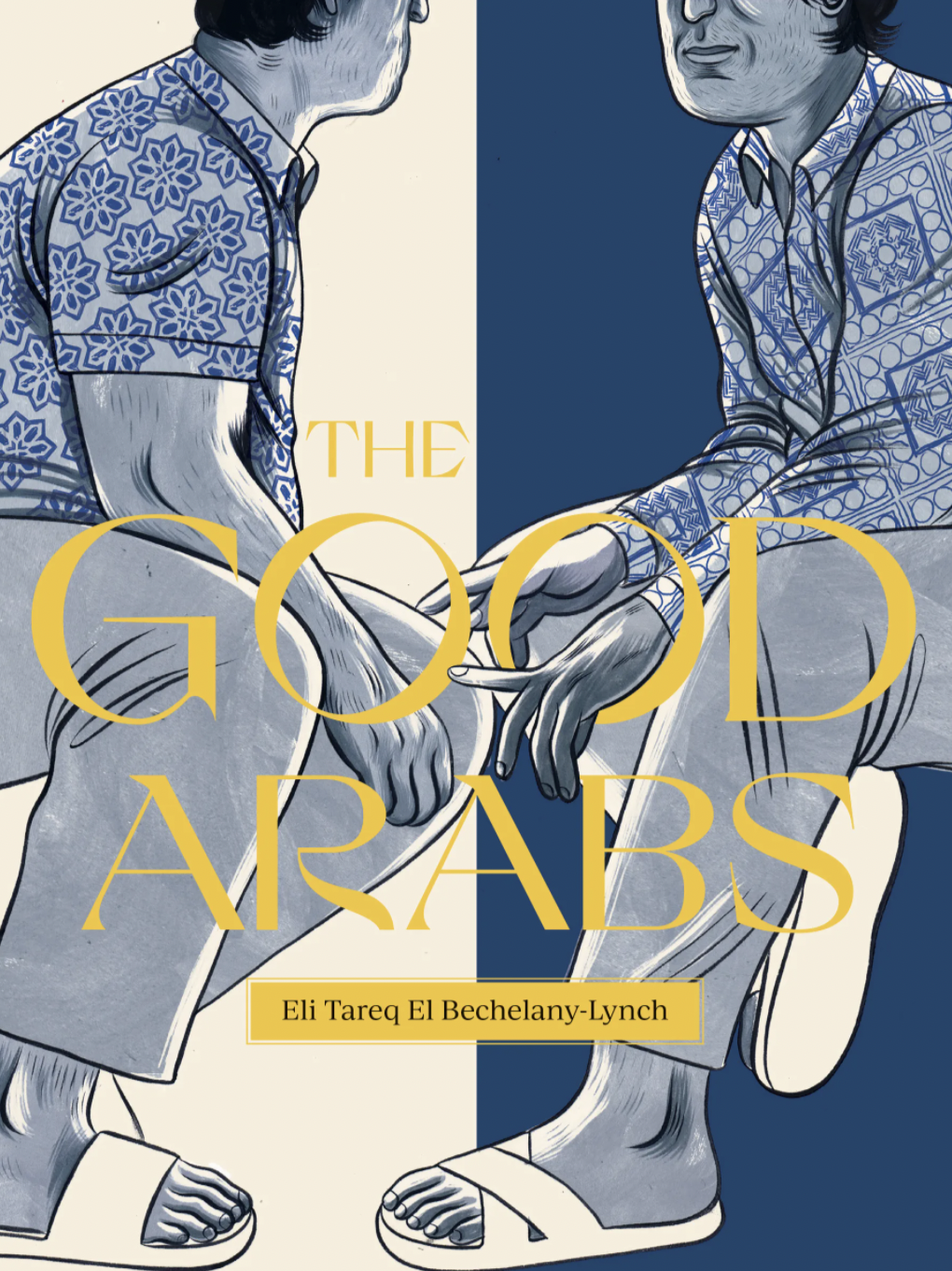

The Good Arabs

In Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch’s new collection, memory reigns supreme. The Montreal-based poet examines and fictionalizes familial memory, weaving in elements of pop culture, politics, religion and mythology.

While their debut collection, knot body (Metatron), addresses chronic illness and disability, the speakers in The Good Arabs (Metonymy) explore gender and racial identity by invoking cultural figures like Nancy Ajram, Cher and Dalida. They recall the back alleys of Parc Extension, Beirut skyscrapers, aunties with their arms linked, cousins dancing, and the joy of queer kinship. “The closing scene is a group of queers bursting into laughter, sides split”, El Bechelany-Lynch writes in their poem “It was.”

We met to chat about craft, gender, language, and the influences central to The Good Arabs.

Angelina Mazza: Who are “The Good Arabs”? What does this title mean to you?

Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch: When I was first thinking of this title, I kept checking with people. I was like, you can tell this is ironic, right? Obviously, I'm not like, “there are certain people who are Good Arabs.” I'm really interested in thinking through goodness and what that looks like, and the ways that people think about good versus bad, or good versus evil, and how it boxes people into certain categories. Especially in thinking [about it] through religion, [where] goodness is based on a set of rules that are created and that often don't even have to do with anything like kindness, or care, or mutual aid, or any of the things that feel really important to me. And thinking through what it means to be a “Good Arab” versus a “Bad Arab,” or a pious, religious, kind Arab versus a terrorist. So, not forgetting the social/political/pop culture idea of Arabs, and trying to push against that as well.

I was struggling with the title for a long time, and when I looked at the titles of the poems I had already written, the titular poem felt so encompassing of what I was trying to write about and the things that I was trying to do. I like that it's ironic, but I also like that it places goodness in association with Arabs.

AM: The Good Arabs explores gender identity and Arab identity. I’m really interested in the connection you establish between gender and language, especially the idea that Arabic has an inherent femininity. The speakers of your poems mention Arabic’s “feminized verbs,” and talk about “releas[ing their] femininity in Arabic,” while “mov[ing] with a body unseen in English.” Can you speak more about that relationship and how it shaped this collection?

ETEB-L: The thing that I was learning while writing the book is that depending on which Arabic dialect you speak, you use pronouns in a different way. In music, you'll sometimes have a man technically singing to a woman, but using what I would consider in Lebanese to be masculine pronouns, meaning that to me, it will sound like a love song between two men. I thought it was really fun to think about people using the language in one way and having other Arabic speakers hear it in a different way. There's this kind of queerness inherent in the fact that different pronouns will be used in different Arabics, and I'm still interested in understanding the history of how that happened––how different areas of the Arab world and different Arabic-speaking countries took the language in as their own and how it has mixed with the Indigenous languages in certain areas.

I lived in Lebanon during my pre-pubescent years, during my time there as "a girl," but also as this kind of non-gendered thing. The period before puberty is when you're allowed to play around more [with gender], especially as a girl. My family really played up femininity, and I think, for me, it was just a fun thing. You would dress up really feminine to go to parties, so I think I saw [gender] playfully in that way. In these poems, I was thinking back through my time there, through memory.

AM: Do you feel like you understand gender differently in Arabic and in English? Has language itself shaped the way that you understand gender?

ETEB-L: I mean, I think it must. One thing is I feel like I have a different personality in whichever language I'm speaking. Because I learned French in the school system, I have more of an “official” kind of language in French, whereas English was always [spoken] more with my friends. Arabic was spoken with my friends but also with my family, so there's a warmth to it. I think that in the ways that gender obviously plays into those things, it’s influenced by whichever language I'm “living in” at the time.

But I think it's harder to talk about because [my understanding of gender] is also influenced by where I was growing up. Back when I was closer with my larger family, there was always this slew of girls and I was put among them. I think that aspect also overlapped with my experience of my gender in Arabic. So, I think it's more experiential than just linguistic.

AM: I was moved by the last couplet of your poem “The Cycle”: “I will not describe to you what violations occur, what a prison looks like, if / only to stop the violence from reoccurring on the page.” I noticed that you allow certain violences to occur elsewhere in the book: the speaker of one poem is misgendered by their boss; people are tear gassed by the police at a protest. As a poet, how do you choose which violences to put on the page, and which ones to withhold?

ETEB-L: That’s definitely a question that I think about a lot as a writer and as a poet, about violence and the everydayness of it, and the deceptiveness––that's not quite the right word–– of not including it. The utopic rewriting of the world if I were not to write violences. I've been in protests where I haven't been teargassed, but where I've almost been teargassed, and I've experienced misgendering. I feel like I know what those violences look like intimately, and it makes it easier for me to write about them in a way that doesn't feel flashy, or that feels kind of there for attention or something.

I think with that poem, in particular, I was thinking about the experiences of people living in Lebanon openly, or at least visibly, as queer and trans people, and my own experiences of being there and visiting, but not living there, because I usually live in Montreal. [As a visitor, I’m] only experiencing a certain kind of violence, but not experiencing the kinds of violence that are both mundane and extreme. Trying to write those violences, I had to choose when to write things and when not to. I’ve never been to prison. I've never experienced that kind of violence from the police, but I've heard about a lot of people experiencing those things. I wanted it to be impactful, but I didn't want it to be…there's a word I'm looking for––

AM: Harmful?

ETEB-L: Well, not exactly harmful, but thinking through who my audience is, and I'm thinking about, for me, a bunch of non-Arabs, and particularly a lot of white people, reading this as like––what do they call it?

AM: Trauma porn?

ETEB-L: Yeah, that's what I was looking for. And I think that line in “The Cycle” was like, it's obviously a heavy subject, but there's also a bit of playfulness in it. I think that felt important to me as well. I don't know if I'm making sense.

AM: Yeah, that makes sense. And when thinking about your audience, there’s the “trauma porn” facet, but maybe there's also the “care” side of things. Would you say that withholding certain violences can be an act of protection or care for your community?

ETEB-L: In some ways, yes. But in other ways…I think that for some people, reading about certain things can be good for them, and not for other people. It's hard to decide the way that people will experience things.

I think I can still be as thoughtful as possible in thinking through how to write things. In my short story, someone gets shot point blank and is on the ground dying, which is obviously a spoiler for that story. That was a choice that felt important to me because you got to know that character. I don't want to paint senseless violence [toward] people without faces. It’s just so particular to what I'm writing about and how I'm writing it, and I think in that moment in “The Cycle,” it felt important to use this poetic veil to both talk about the violence and also kind of poke at the audience.

AM: A recurring element that surprised me is the “Conversations with Arabs” poems, which are fragments of conversations between unnamed characters that are spread out within the collection. They read like theatrical dialogue. I understand these poems as an invocation of community and as an invitation into the conversations that your speakers are having about Arab identity, politics, anti-Blackness, and craft. Can you elaborate on your decision to bring in several voices?

ETEB-L: The “Conversations with Arabs” were kind of the last thing that I wrote. There was something missing in the book, and I was trying to figure out what it was––it was mostly just a feeling. I could tell that there was a grounding and uniting force missing in the work. I was initially inspired by my partner [Helen Chau Bradley] who is also published by Metonymy. In their collection, Personal Attention Roleplay, there’s the story “The Queue” that's just [written in unattributed] dialogue. They were inspired by a Russian novel called “The Queue” and they wrote their own interpretation. That inspired these “Conversations with Arabs” because I was like, Oh, that's actually perfect. What I need is not more poetry; I need dialogue.

I wanted to create poetry out of dialogue and wanted the snappiness and the movement I could create from that. I was thinking about these conversations that commonly happen. Like, there's the “Conversation” around who’s paying the bill––I've seen so many Arab comedians talk about this because it's so common [to fight] over the bill––and I wanted to change it a bit. I wanted to bring a fresh look at these conversations, but I also wanted to get at some real subjects, like discussing anti-Blackness. It felt hard for me to do that in a poem. I think trying to write about those kinds of big subjects in poetry can fall into didacticism very quickly. The “Conversations” gave me a lot of room to address things without also having [to provide] easy answers. I think didactic work tries to find answers and solutions. The “Conversations” were trying to get away from that because there aren't going to be easy answers. To question, at least for me, feels like such a good way to start and to continue to think about things. When we think that we have the answers, we lose some nuance because none of these big topics or questions have simple answers. I also really enjoyed creating these characters. I’m interested in the middle space between poetry and prose and the “Conversations” really felt like a fun way to play with that.

AM: Some of the poems in The Good Arabs are in conversation with the work of Danez Smith, Jericho Brown, and Claudia Rankine. Are there poetic traditions or writers beyond those three poets that have significantly shaped your craft and the writing of this collection?

ETEB-L: I'm really a poet's poet in the sense that I love poetry and I can't write without reading. I wrote this book alongside other books, like Dionne Brand's The Blue Clerk and Kaie Kellough’s Magnetic Equator. I was also reading Trish Salah's Wanting in Arabic. I was reading ghazals by a lot of different Arab and South Asian writers because I got really into ghazals when I first read Trish Salah's work. A friend lent me her book a long time ago, and that was really exciting because I was like, Oh, another mixed-race Lebanese trans poet. I was really stoked that someone like that existed––someone so close to my own identity whose work I really loved. I started writing ghazals after reading her book and it felt like an important part of my research and poetic lineage to work through the ghazal in my book.

Jericho Brown's The Tradition was also really important in writing this book. A lot of Arab writers, but also a lot of Black American and Black Canadian poets have been really influential to me. Anne Boyer’s work was important to my first book, knot body, but I think her poetic voice has been really important in thinking about how I want to write poetry. If I'm in a place where I can't write at all, I pick up a book of poetry and read through some poems that I like, or I search the Internet for new stuff that I haven't read, and it really gets my brain going. There's so much good writing out there, and I want to be in conversation with those people. I owe a lot to other writers.