‘Kids don’t care about diseases. They care about sex.’

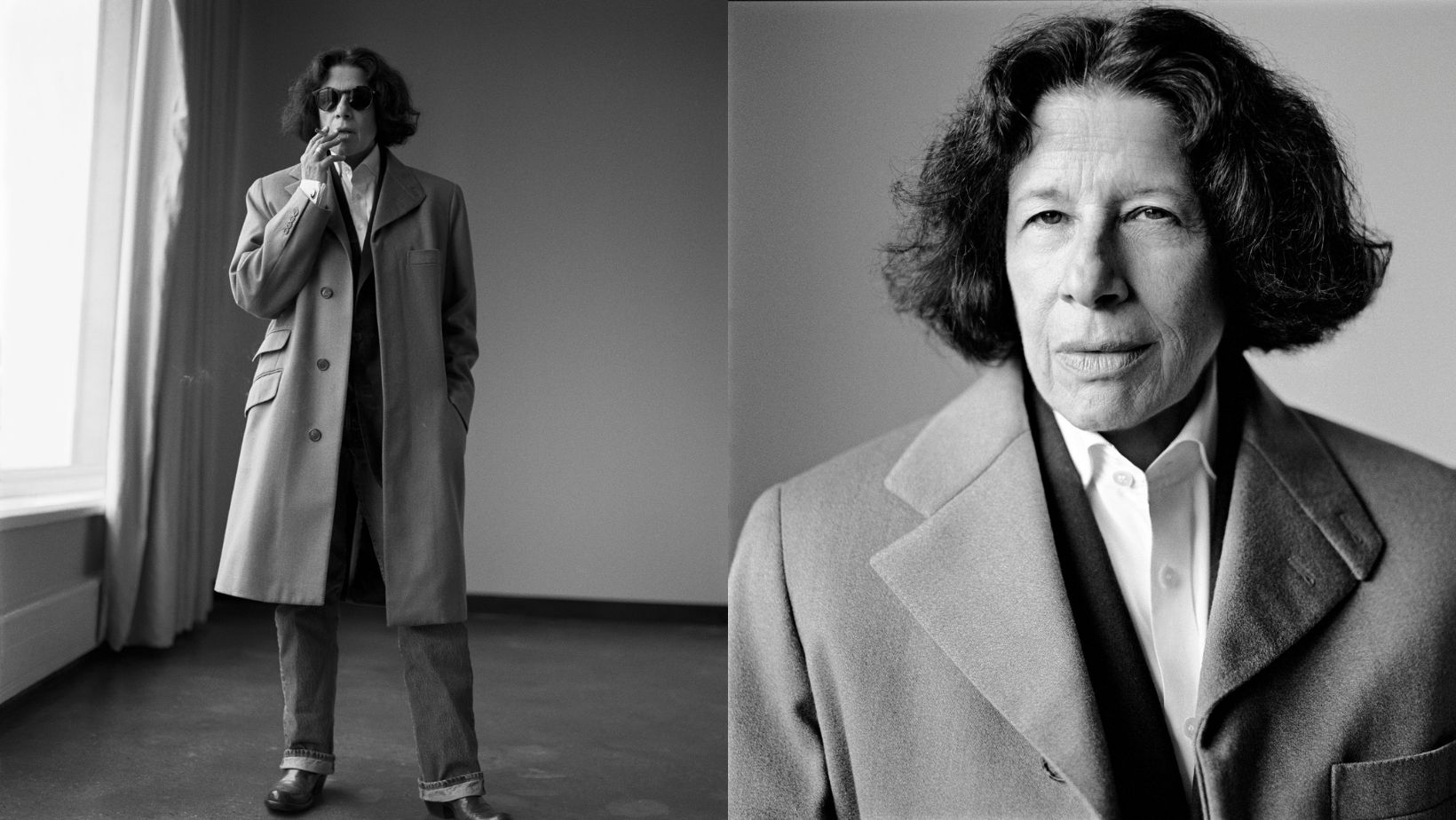

The New Yorker’s New Yorker, the ultimate urbanite, the dashing and very metropolitan Fran Lebowitz is a fast-talking treasure. Her observations on the nature of people, politics and cities are both scathing and funny because they’re so often true.

Born in 1950, Fran Lebowitz arrived in New York City in 1969, where she held a number of jobs including driving a cab and working for Interview magazine alongside Andy Warhol.

Although famous for her writer’s block, Lebowitz is the author of several books including Metropolitan Life (1978), Social Studies (1981), and The Fran Lebowitz Reader (1994). She has worked as an actor for TV and film and has been featured in two documentary projects by her friend Martin Scorsese, most recently the 2021 seven-episode Netflix series Pretend It’s a City, and also the 2010 film Public Speaking.

I called her answering machine, she picked up the phone, and we spoke together in late March.

Melissa Bull: So, New York is opening up again. Is it back to any kind of normal? Are the tourists back? Is anyone wearing masks? What’s life like there these days?

Fran Lebowitz: Well, I’ve only been back about a week; I’ve been on the road for about a hundred years. And it’s also like a thousand below zero here—it’s so cold, I think last night was 12 degrees or something. Many people would not go outside in that weather, and I can’t say that I blame them. There are tourists here, I mean there aren’t anywhere near the number there were before Covid.

MB: So, is that the biggest post-pandemic change?

FL: To me, the most obvious thing is that people didn’t go back to work. And this idea that New York is all about tourists—it just isn’t true. Obviously, when it is truer, it’s also bad. A very significant number of people didn’t go back to their jobs in offices.

MB: It’s weird right? The downtown core of Montreal is similarly empty at the moment.

FL: What’s weird was that I was back in Europe for like ten to twelve days like a week ago. Obviously in general you would say that Copenhagen has nothing in common with New York. But it seemed to me to be the case. And I was in Copenhagen, Paris, Athens, Stockholm, and these places are very different from each other, but it seemed very clear that people had gone back to their jobs. I don’t want to be on record saying this is actually the case because I don’t know for a fact. But here—and when I say here, I don’t just mean New York, because I’ve travelled around the country a lot in the last few months—in this country, people, employers seem to have asked their employees if they would like to come back to work. And funnily enough, people have said no they would not like to come back to work. But in Europe, apparently, employers said everyone’s going back to work, and now everyone’s gone back to work!

So if people do not go to their offices, then this has nothing to do with tourists or no tourists or Broadway shows or restaurants. Those things are not the economic engines of cities, really. New Yorkers don’t really think about what the economic engine to all five boroughs is. It’s not Broadway shows; it’s not restaurants. So, you know, Midtown Manhattan is very clearly underpopulated by office workers. And because they don’t go to the office, then everything around is closed. They don’t go to the drugstore, so the drugstores are closed, and when I say closed, I mean for good.

MB: Same here. Downtown Montreal has a strange, uninhabited vibe, too.

FL: I was in San Fransisco what seemed to be like 8 billion times one month and I stayed in a hotel in what used to be the Financial District which also has big business and a shopping district—it was empty. And everything was closed. I went out of my hotel to buy toothpaste, not a hard-to-find substance, it’s not like I was looking for truffles or something, and I couldn’t find a place to buy toothpaste. And this is in what was a very, very densely occupied place, before. But in the middle of the day in Copenhagen or in Athens, the streets are packed with people. Why? Because they’re going out to lunch from their jobs.

MB: That makes sense.

FL: I understand people don’t want to go back to work. I get that. It’s like asking children if they want to go to school. No! I also believe that the people who are not going back to work are kind of living on the residue of when people did go back to work. Because there is no way that—it’s almost like a car driving 80 miles per hour—you can put the brakes, but it’s not going to stop right away. I think, in the end, more people will have to go back to work. But if they don’t, then, you know what’s going to happen to cities—not just New York.

MB: Yeah, I’m from Montreal, but this post-pandemic Montreal is a city I feel like I don’t always recognize anymore.

FL: What’s bad is that people in power—for instance here, we have a new mayor, who is as I predicted even worse than the last mayor. And he’s very concentrated on these kinds of dopey things. When I say dopey, I mean, you know, restaurants. You know what? I eat in restaurants all the time—I hate to cook, no one loves restaurants more than me. But restaurants are not the main thing. The main thing is offices. I know that sounds horrible, but the thing is kids go to—and when I say kids, I mean people in their twenties—kids don’t care about diseases. They care about sex.

I keep saying to my friends, “Don’t you remember being young? Yeah, of course, they’re out!” At four in the morning, I go across town in a car, and the driver couldn’t get across the street; there were hundreds of kids in the street. And the driver goes, “What’s going on here?” and I said, “There must be a club here.” This is like two blocks from my house. And he goes, “What club?” And I go, “How on Earth would I know? I don’t go to clubs!” But I recognize that if there’s a million kids in the street there’s a club, and they’re going to go whether there’s a contagious virus or not.

This isn’t something the mayor has to concentrate on. This has nothing to do with the mayor. This is just what humans do. And the same thing too of restaurants and things like that. So, I don’t know the future. Obviously, if I knew the future, I wouldn’t buy the wrong lottery ticket every week. I don’t know what’s going to happen, but it’s not anything to do specifically with New York, because I’ve seen it in every city that I’ve been in, and I’ve seen it all over the country. And I’ve seen the opposite in Europe, where the only explanation for this is that they didn’t ask people if they would like to go back to work or not.

MB: Well, Europeans also have better health care than Americans.

FL: Everyone has better health care. We have no health care. We have heath care the same way that we have Cartier. If you want to buy a diamond bracelet and you have the money for it, we have a store for it. So, yes, if you have money, and you want health care, yes, you can buy it. But otherwise, no, we don’t have it.

MB: The other day I decided I was going to try to figure out what the alt-right are really about. I’m from a left-wing arts family; they don’t make any sense to me whatsoever. So, I thought I’m going to try to listen to them and see what they’re thinking, to at least try to understand. So, I went down this terrifying internet rabbit hole, and apart from bashing women and LGBTQI and minorities and heath care and education, it seems like what they’re super into is all meat diets and sending oligarchs to space. Obviously, I’m over-simplifying… What’s your take?

FL: It’s very easy to understand if you just understand that centrally, it’s just racism pure and simple. That is centrally that’s the appeal of Donald Trump. That is what appeals to these people. Basically, that racism and then concurrently also about misogyny.

MB: Of course.

FL: It’s not really complicated. It only seems complicated if you start from the point of view of, you know, like, why would people act this crazily. Because it doesn’t seem crazy to them. You know, that’s the thing you have to understand. They think that they’re right. Because they believe in these things that are not true. It’s as simple as that. In other words, they believe in the superiority of white people. They believe in the right of men to oppress women. They believe immigrants are taking their jobs. They believe that stuff. Basically, this is fear, but it’s really misplaced. Here’s the thing. If you were a poor or lower middle class white person what you could always fall back on was that you were white. So maybe you weren’t making enough money to really live, and maybe your life was in total disarray, on other hand, you were white. So, if it starts to dawn on them that this is maybe not enough, they become terrified. And you know, this thing of immigrants has always been used in this country. Always.

MB: Here too.

FL: This is in Europe, too. This is everywhere. Except basically in New York. You know, I’m sure we have racists in New York and I’m sure we have misogynists in New York, but you know it’s very rare to hear real anti-immigrant things voiced here because it’s so clearly a city of immigrants. To me, it’s like super clear. Until like maybe Donald Trump, it was a thing I never really thought much about and maybe about 15 years ago I was doing a speaking date in Arizona, which is a border state, and the first question I got from the audience was what did I think of immigration, and I was stunned by this question—like what are you talking about? Like—who thinks about this? And it turns out half the country thinks about this. And it turns out that half the country thinks about this in the same stupid way they thought about it a hundred years ago. And they will think about a hundred years from now. This is worse than it used to be because they have less. In other words, these people, these Trump people—and they’re all over the world—have less and less.

MB: Yeah, for sure

FL: Instead of looking into why they have less and less, they just believe they have less and less because obviously some immigrant took away their job. Despite the fact that they might look around and see the factory is gone. The factory is gone, it wasn’t taken by Mexican immigrants who make six dollars an hour. The factory was moved by the rich guy who owns the factory. So, you know, is it surprising? It’s not hard to understand. It’s hard to understand if you’re going to believe their explanations because their explanations are lies.

MB: I just rewatched Martin Scorsese’s Pretend it’s a City and Public Speaking. One of things I particularly love about both projects is how much Martin Scorsese laughs when you’re talking; I can see how delighted he is with you, and it’s a pleasure just to watch him really cracking up. How did you feel about making this latest Netflix series with him?

FL: Well, the thing is there was about ten years between those two projects. So, you’ll notice I look quite a bit younger. Truthfully, I know no one believes this, but when we’re filming, I’m not really paying attention. I mean, it’s pretty much like how I’m talking to Marty. The difference is when I’m talking to Marty, at dinner, or at his house or something, obviously Marty talks half the time—I don’t talk all the time; Marty’s not just asking questions. So, what you don’t see in either of the movie or series is how funny Marty is. So, if you saw us having dinner, you would see me laughing the other half of the time. So those things, those parts of it are really fun, really.

The parts where you see me walking around, those are pretty tedious. Although you may see me walking across the street and it’s two seconds, what you don’t see is the 50 times they made me walk across the street because she didn’t get the shot she wanted. Making these things, the making part is tedious, which of course you don’t see because who wants to see the tedious part? This is true of anything you make. Originally, before we started doing the series, Marty said, “Let’s walk around New York together, and then we’ll be filmed talking while we walk around.” Well, this is much harder to do, first of all, but also because Marty hates being recognized. So, I said, “Marty, this will be fine. Except every two feet, someone’s going to say Marty! Or Mr. Scorsese! And we’re going to get stopped.” So, I actually got him to agree that this was the case.

But then one day he said, “I’m going to come.” We were shooting in SoHo, and within two seconds Marty was hiding in a doorway. You know, first he was talking to me in the street, and two seconds later, there were too many people talking to him, which he really dislikes. I don’t dislike it when people talk to me in the street, but Marty really hates it. So, he was hiding in a doorway—literally pasted against a door—so no one would see him. So that didn’t work out—as I expected that it would not.

MB: I really want to touch on your style, which I’m a big fan of. I love how consistent it’s been all these years. You’re known for your cowboy boots, in particular, but I noticed you were wearing those CSI-type crime slippers when you were in the Queen’s Museum for Pretend It’s a City, and I wondered how you felt about those, because I feel like you must not have felt entirely dignified in those little blue slippers.

FL: First of all, the guy in charge of that exhibit, which is this miniature New York, had never let anyone do that before. Apparently, and luckily, I was not party to this—there were days of negotiations with this guy. So, he was incredibly nervous about letting people go in there with cameras. So, I was there for hours and hours and hours while Marty set up the shot. There’s a balcony that goes around the exhibit where, when the museum is open, people who want to look at that exhibit, they don’t walk onto that [platform], they walk around on a balcony. Marty brought like five cameras in there, and it’s very hard to shoot from a balcony into the middle of a place. So apparently the guy was already having a nervous breakdown just with the crew in there for hours. And then I said I didn’t want to wear those things. So, he said, “You can’t walk in there with your shoes.” I said, “Okay, I understand. Why don’t I just take my shoes off? And I’ll walk in my socks.” “No!” So, I don’t remember if I had those things over my cowboy boots or just over my feet, but I thought the guy was going to have a heart attack in front of me because at a certain point I knocked over the Queensboro Bridge.

MB: Oh no!

FL: Marty always uses a huge number of cameras and lights and stuff. And I don’t pay attention to it; I don’t understand it, it has nothing to do with me. And because this guy was so hysterical, I was so aware of it and then twenty-five people went, “Oh no!” And I looked down and luckily it just knocked over—I didn’t break it. But I looked up and the guy and he looked like I shot him in the heart. And I said, “No I didn’t break it, look it’s fine.” I must say it was pretty nerve-wracking even though I actually went to the World Fair in 1964—and I went twice—I didn’t even know [the museum] was there. And I had never even heard of it— which is really surprising—and then a friend of mine happened to go to the museum and he told me about it. I cannot stress enough how people should go. The only good thing Robert Moses ever did.

MB: So, on a regular day, do you wear your cowboy boots indoors?

FL: Yes, I do, I mean, not in my house. In my house I wear moccasins. But in other people’s houses, or anywhere I go, I wear the cowboy boots. I don’t know about Montreal, but about eight or nine years ago, people in New York started to request that you take off your shoes when you go to someone’s house, which I find so ridiculous. Someone was coming to my apartment once and she said do you want me to take my shoes off? And I said no! I think it’s ridiculous.

MB: I guess it came out of a fear of germs, but now at this point we’re all scared of germs.

FL: No one should take their shoes off to come to my apartment. When I was looking for an apartment, the many times I have been, when I got to this apartment to look at it, the broker she just takes her shoes off. And I said why? And she said because they have a baby. Like a little baby that crawls on the floor. I said, “Really? Maybe I don’t want to take off my shoes because I don’t want to walk on the floor where the baby’s crawling. Did that ever occur to you?”

MB: In the “Library Services” episode of Pretend It’s a City, you say, “The book is the closest thing to a human being. I cannot throw them away.” I love that—I think of books as my friends. But I have a little problem with library fines, so I buy most of mine. What about you? Do you tend to borrow books from the library or are you more of a bookstore person?

FL: Well, when bookstores are open, I go to bookstores. And during the lockdown, when everything was closed, I was reliant on the worst possible combination of things: reviews, which are almost always wrong, recommendations from friends, which are sometimes wrong, and a friend’s Amazon account. So, when I go into a bookstore, I pick up a book and I read a few paragraphs, and I’m pretty good at telling, at this point of my life, I don’t think I’m going to like this or I’m probably going to like this. And I’m pretty much always right. I probably have about 150 books right now that I would have never bought in a bookstore. I look for homes for them, because I don’t want to keep them.

MB: Have you read anything particularly good lately?

FL: I would say that the last book, the most recently published book that I recently liked was Colson Whitehead’s Harlem Shuffle. I liked that a lot. I can’t think of any other recent novel that I like enough to recommend.

Fran Lebowitz will be speaking in Montreal at Église St-Jean-Baptiste May 6, 2022. The event will be hosted by journalist Josh Freed. Tickets are available here.