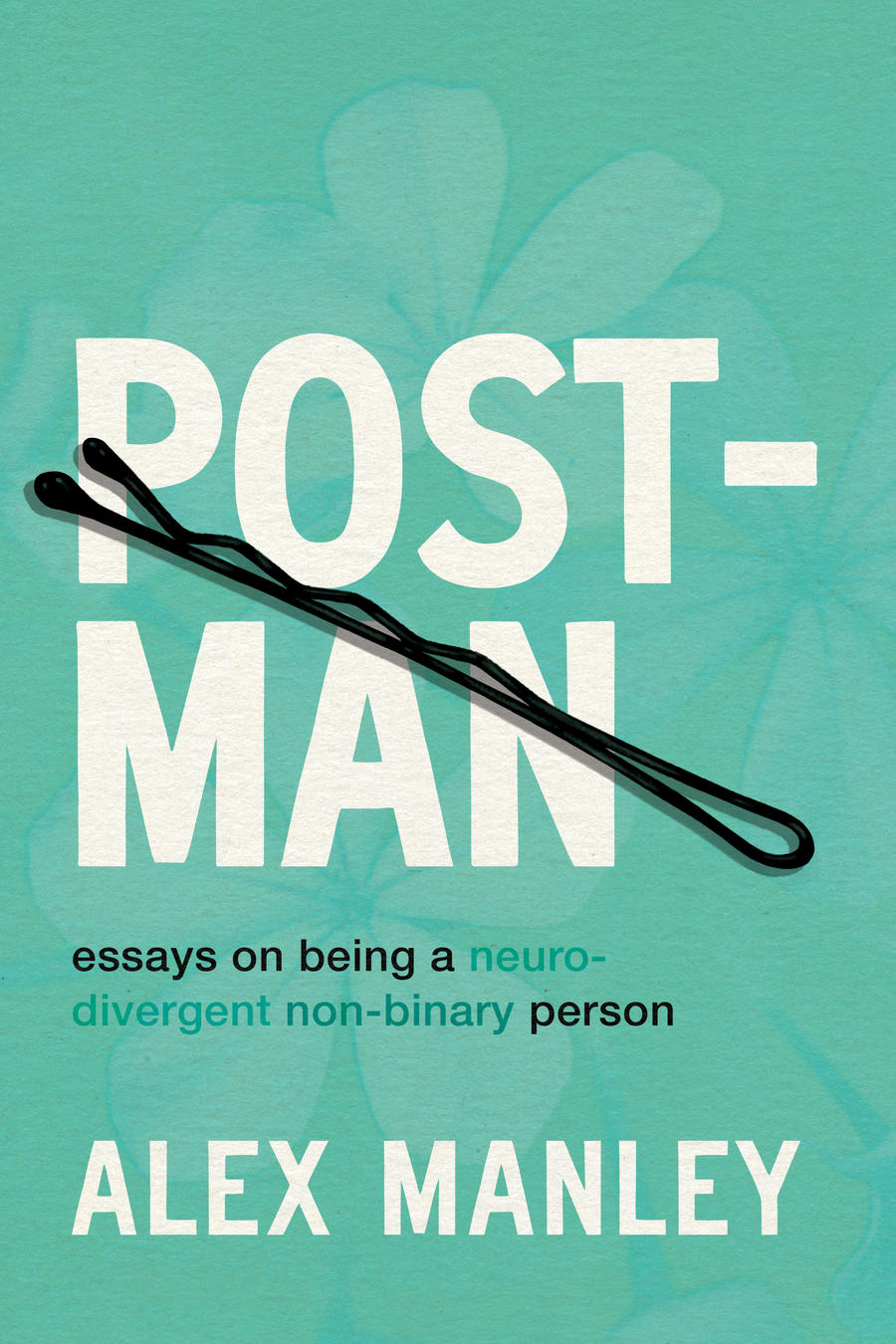

Post-Man

Navigating masculinity can feel impossible. It involves a bewildering set of expectations, from physical prowess and emotional stoicism to communication with other men through a hyper-competitive bro-code. As a neurodivergent, non-binary person, Alex Manley has long felt at odds with the assumptions thrust on them; their new essay collection Post-Man (Arsenal Pulp) reckons with the weight of a world not built for them.

Gender norms are just one facet of the myriad systems shaping our bodies and behaviours. The pithily titled “The Lead Essay” shines a light on these influences—whether socially constructed or literally built into the city—using the dangerous amount of lead lining Montreal’s water pipes to exemplify the enmeshed toxins that surround us. Manley connects lead exposure to its symptoms and siblings, including violent crime, pesticides, paint, car exhaust, and dirty water in First Nations communities—the institutionalized, subtle violence of capitalism that many are all too aware of, yet which remains seemingly impermeable, a fixed reality.

It is a thrilling essay. As Manley teases out the link between toxins in urban areas and cognitive decline, I had the sense that I was unveiling a vast conspiracy, eyes opened to previously obscured connections. Towards the end of the piece, Manley pronounces what could be Post-Man’s thesis: “We are all—St. Louis boy, pregnant mothers, GM workers, all of us—born into a cage, a series of dangers laid out to ensnare us by forces beyond our awareness, understanding, or control.”

Manley is interested in the absurdity of cultural expectations for men, the ways they are forced to contort themselves to fit the cage’s dimensions. “Behind the Masc” examines the paralyzingly rigid masculinity ingrained in hockey culture. For the tough hockey player, even going to museums in their spare time is perceived as a slight on the boys. What Manley calls the “aesthetic beauty” of the sport seems purposefully blunted with this oversized machismo. In “The Content Mines,” Manley describes their perplexing experience as a copy editor at an online men’s magazine in the mid-2010s. The masculinity exported through their clickbait articles, however casually stereotypical—articles about porn actors and poker players—comes off as almost quaint compared to the nihilistic manosphere content of today.

Manley is unafraid to expand upon themes slowly, letting focus wander with trust in the reader’s capacity to follow. Their prose shines most when evincing the profound and often senseless ways social determinants shape our lives. When Manley narrows the focus to their own experiences, the writing can be less effective, with some essays so personal they seem to plead absolution from the reader. The essay “How to Come Out as Non-Binary If You’re AMAB” describes a catalysing factor in their coming out: a distant friend emailing to sever the relationship, claiming their behaviour made several women uncomfortable. Manley is upset to be perceived as a predatory man, and while their honesty is brave, the prose lingers in pain, veering towards inward rumination rather than pulling back to offer a broader cultural critique or analysis. Essays on rattails and jay-walking are engaging but slight, also lacking the breadth found elsewhere.

At other points, this vulnerability is deployed more successfully, as when Manley highlighs the difficulties of maintaining ideals in a material world. At the end of an essay reflecting on the experience of balding as a non-binary person, Manley reveals that after the piece’s initial publication they accepted a company’s hair transplant offer, knowingly conceding to the same beauty standards they had previously questioned. As a student working at a corner store, Manley feels guilty about selling drug paraphernalia, but still treats their customers harshly, wielding their limited authority. A fear of innate complicity seems to haunt Manley’s writing. They ruminate on “the bells that can’t be unrung,” our immutable capacity to corrupt and be corrupted.

Is it futile to yearn for something more, to be purified of the world’s influence? In between the essays, brief second-person proclamations of gender euphoria (and dysphoria) appear in faded ink, as if Manley is whispering to themself. “The gender binary is a net that is thrown over us over and over and over and over and over. A net from which some people wish to disentangle themselves. A net for whose ropes I am seeking out a sword. A knife. Something to cut with.”

Like the residual lead embedded in our muscle tissue, we cannot easily shake off the expectations of gender norms and conceive of a universe beyond the binary. I’m reminded of the scholar and theorist José Esteban Muñoz’s musings on the inherent futurity of queerness: “Queerness is not yet here. Queerness is an ideality. Put another way, we are not yet queer, but we can feel it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality.” While we may appear frozen in this defective present, Manley’s thoughtful, searingly honest book gestures towards that warm horizon with conviction.

Josh Milton-Bell is a British writer and editor based in Toronto.