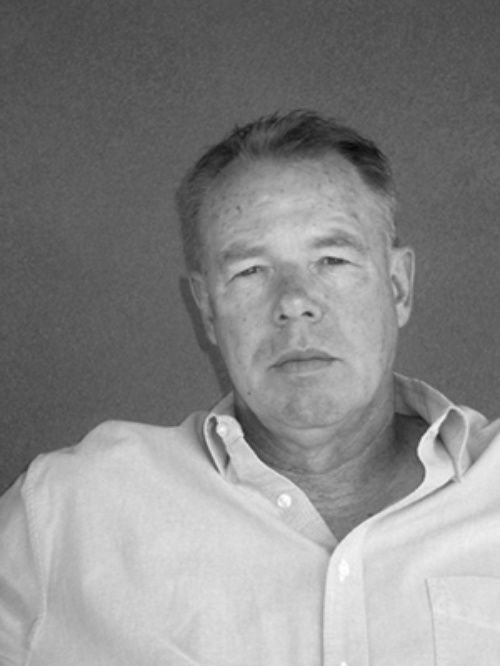

The SLS Interviews: Kevin Canty

The Everything author on Montana, the rhythm of writing and why he still makes mistakes.

Kevin Canty is a kind of alchemist, a writer who can produce intense meaning with few words. He's no minimalist, though. His short stories and novels are rich and dense and play with language in a manner that would have him expelled from whatever building the minimalists gather in. Canty's prose lives in a very real world, a kind of place that is inhabited by sons and fathers and mothers and wives and neighbours, living life, having drinks, suffering consequences to actions they didn't think were important, living in ways that are surprising to them and to us, as readers, because we see ourselves in these fictional lives, we see our own unfolding, the way our lives become something else before we even realize it, and this is really what drives Canty's work.

A professor of writing in the MFA program at the University of Montana, Canty is the author of seven books, most recently Everything, a novel. His stories have appeared in GQ, Glimmer Train, Esquire and the New Yorker, and his essays and articles have appeared in the New York Times, Vogue, Playboy and other publications.

Arjun Basu: The land is so important in your work. There is always landscape in there, in your shortest short stories and in your novels. And not just the grandness of the Montana landscape, or of nature even; the urban environment is present, the lived environment, making it obvious that all of your characters, and your stories, are of a place. How important is the landscape to the story? Is landscape narrative?

Kevin Canty: I guess it's just part of the way I see things, rather than being present at the level of intention or idea. I think I'm kind of an intuitive writer; it's not like I don't have ideas, but the way they make their way into the written work is kind of circuitous and accidental.

But with that disclaimer out of the way, I did notice that these last two books were very much set in Montana and the West. There are a lot of trees and skies and rivers, I think because the people who are drawn to this place are the kind of people who notice these things. I was walking my dog up on the mountainside the other day and I noticed that the shooting stars and glacier lilies are out, which means that it's really spring (even if it is still snowing a little from time to time). I imagine if I lived in Brooklyn I would be noticing shoes or haircuts or eyeglass frames the same way—or maybe the passing seasons in the park.

I think we live in narrative. In some sense it's what we're made out of—these stories we tell ourselves about who we are and what we're like and what's important to us. I think these things are in some genuine sense fictions, which is not to say they're unimportant. In fact, they're vital. Lose that story about yourself, do something that contradicts that story, and you'll find yourself in a very difficult place. So there's this scramble for confirming detail: I am the person who wears these shoes, has this haircut, lives in this place, gives to the homeless shelter or the art museum. Is there something slightly desperate about this?

AB: There's a passage in Everything, where June asks herself: How did it come to this? And this simple line seemed to me the thrust of your fiction. People trying to figure out how they got to where they are, or showing the moments when those little moments occur, unbeknownst to the characters themselves. The insignificant parts of life that accrete and then suddenly become continents. Are you drawn to these moments? Do you see them before anything else?

KC: I'll answer in the words of Emily Dickinson:

Crumbling is not an instant's Act

A fundamental pause

Dilapidation's processes

Are organized Decays.'Tis first a Cobweb on the Soul

A Cuticle of Dust

A Borer in the Axis

An Elemental Rust—Ruin is formal—Devil's work

Consecutive and slow—

Fail in an instant, no man did

Slipping—is Crash's law.

In fact an early title for Where the Money Went was "Slip," which I probably shouldn't say because I'll probably want to use it down the line. I'm really interested in the moment when something that's been working just below the level of consciousness becomes visible, starts to work or to unfold. It's like, you're married, you're married, you're married and then suddenly you're not married anymore and you're like, how the fuck did that happen? And in retrospect there's always an explanation—which is generally just a story, a fiction, maybe a falsification. Again, it's a necessary fiction. Because events themselves have complex beginnings and complex consequences, there aren't any simple stories.

But no, I don't see anything any better than anybody else. Maybe worse. This is probably why I'm a writer, this inability to understand anything in the present moment. I want to go back and try to understand.

AB: You grew up in a musical household. I'm guessing that, given that your brothers are musicians. And I do sense a strong sense of rhythm in your work. Would you describe your work as musical? Did growing up with music influence your work in any way?

KC: I'm a player myself, have been forever. I'm still playing guitar in three bands around town here, having fun and making a racket. Somehow that informs the writing, though I'm not quite sure how. I move my lips when I write, tap my foot when I read aloud. I think there are people who write for the eye and other who write for the ear, and I'm definitely in the ear camp.

Really, though, I suspect this has more to do with getting my start as a poet. When I got to Montana in the early 1970s, Richard Hugo was still this giant presence here, a legendary teacher and a truly great reader. All the energy and excitement were in poetry and I pursued it for a few years despite having no visible talent for it. I still read a lot of poetry and steal what I can. And there's something about the idea that work is incomplete up to the moment that it's read aloud—the way it transforms from an idea into something that you're doing with your body—that I still really love and respond to. But I don't try to write poetry anymore, at least while sober.

AB: Does this sense of music and rhythm inform your own public readings? Poets have a much better time reading, I find, because of that sense of performance. Fiction is a whole other beast and not always satisfactory.

KC: I think it does. This sense of rhythm is a big part of how I work, trying to fit things together in complicated and satisfying way. That's a lot of where the fun is for me. This last novel, for instance, I wrote without quotation marks around the dialogue, just to force myself to get the rhythms right so the sentence would lie naturally on the ear. I intended all along to go back and put them in again but I found, at the end, that I felt like I didn't need them. There's a sense that poets do this, fit the music of the language to the emotion, but fiction writers don't have to—but this seems completely wrong to me. Stories are made out of words as much as houses are made out of bricks; carelessly laid words will make an ugly mess of the whole thing, no matter how brilliantly conceived.

AB: As a teacher, what is the first thing you teach your students? And how much of your writing informs what you teach?

KC: Backwards first: without the writing I'd have nothing to say, nowhere to stand. Every single thing I've ever learned about writing, I've learned from a brilliant writer: Bill Kittredge, Joy Williams, Padgett Powell, Harry Crews, many many more. I keep hearing rumors of a teacher out there somewhere who's not much of a writer but a brilliant teacher of writing, but I don't believe this mythical beast exists. I feel like everything I do in the classroom is grounded in my daily practice of writing. Without that, I would literally not know what I was talking about. This happens a fair amount anyway.

As far as first things, there are a million of them. I don't know if there's a systematic way of teaching writing; there are too many little moving parts to it, too many facets, too many trade secrets and experiential discoveries. I learned writing by practice, making today's mistakes today and tomorrow's mistakes tomorrow. This is the only way I know to develop your craft. You can't just sit around and think about it; you have to sit on your ass in front of a computer (typewriter/legal pad/whatever) and do it. In that sense, fiction writing can't be taught—but it can certainly be coached. I am hugely grateful to my teachers over the years for the time they have saved me and the stupid mistakes they tried to keep me from making. I'm also grateful to the stupid mistakes I kept on making because they finally, painfully, taught me to stop making them. The old mistakes, anyway. I'm still making new ones.

AB: What does a writer get out of a workshop, especially one so concentrated as Summer Literary Seminars? How will you approach the conference?

KC: As Sherlock Holmes put it, everything depends upon the Psychology of the Individual. Different writers come to SLS with different needs and ambitions. My workshop in Montreal last year was wildly mixed; a few people who were pretty close to the start of their careers and others who were really polished and ready to publish, even a few who had started to publish well. What they did have in common was a lot of energy, a lot of excitement, a lot of ideas. They really fed off each other's enthusiasm, generated a lot of sparks. I think everybody went home with a couple of new friends and a satchel full of new ideas about writing. I think that's what a short, intense workshop like SLS can do, give you a bunch of new approaches, new ways of thinking about writing, that you can then take home and try on for yourself and see which ones may fit you.

The writing friendships can be worth their weight in gold, too. It's hard to learn to write and for some of us (myself emphatically included), it can be a long apprenticeship. It's really nice to have somebody to talk to who doesn't think you're crazy for trying. I mean, seriously, even your Mom thinks it's kind of a bad idea. You're not going to call her up and talk about Isaac Babel and semi-colons. It's awfully nice to have a phone number or an email address of somebody who actually cares about this stuff as much as you do.

Arjun Basu is the content director for Spafax, a leading custom content provider and the former editor-in-chief of enRoute, Air Canada's in-flight magazine. He is also the author of a book of short stories, Squishy.

As part of Montreal's Summer Literary Seminars, Kevin Canty, who is conducting fiction workshops throughout SLS, is reading Wednesday, June 22, at 7:30 p.m. at Concordia's DeSeve Hall, with Jon Paul Fiorentino and Katia Grubisic.

Montreal's Summer Literary Seminars take place from June 12 to June 25, 2011. For a schedule of events, or to buy a pass, visit www.sumlitsem.org/montreal/schedule.html

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—The SLS Interviews: Gary Shteyngart

—The SLS Interviews: Adam Levin

—The SLS Interviews: Lynne Tillman

Follow Maisonneuve on Twitter — Like Maisonneuve on Facebook