Should Occupy Wall Street Take Up Arms?

American history is full of revolutionary violence. Will the Occupy movement follow John Brown's example?

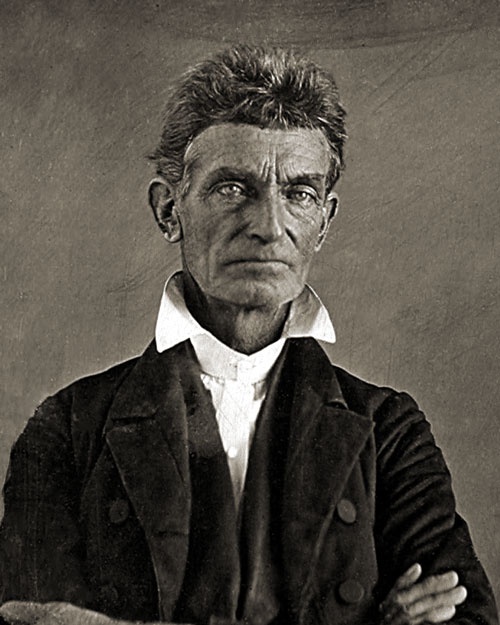

SOME PEOPLE call John Brown the first terrorist in American history. He was a religious fanatic. He attacked homesteaders in Missouri and liberated quite a few slaves in the process, bringing some of them to Canada. He murdered slaveowners in defiance of their right to pursue happiness. He attacked an armoury at Harper's Ferry, Virginia, a crime for which he was hanged following a week-long trial, on October 16, 1859. Fellow white abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison considered Brown a misguided soul and a discredit to the cause. Today, some people call Abraham Lincoln, Brown's contemporary, the most important man in American history; by the logic of American Exceptionalism, Lincoln is also, therefore, the most important man in history, period. While John Brown was gathering arms to start an insurrection, in the hopes of preventing the expansion of slavery into new American territories, the Great Emancipator was gearing up to run for the country's highest office.

As president, Lincoln made some controversial decisions, like suspending habeas corpus. Habeas corpus is complicated to explain, but let's say that, while it does not protect American citizens from unlawful arrest, exactly, it does mean the police must release the citizen if an unlawful arrest has occurred. Habeas corpus does not, however, stop police from arresting people for resisting possibly unlawful arrest. (YouTube and other sources suggest that several hundred unlawful arrests have likely occurred in America in recent weeks.) But Lincoln's main job involved the reconciliation of higher ironies inherent in contradictory, foundational American slogans: all men are created equal, the pursuit of happiness, e pluribus unum or out of many, one. By winning the Civil War and freeing the slaves, Lincoln also helped the northern states take the southern states' labour supply. The Emancipation Proclaimation is what we remember, not that John Brown risked all and won nothing but the right to haunt American history from then on. Moreover, not only did Brown fail to free the slaves himself, but years prior to his tragic campaign he experienced a certain personal loss: "Creditors took all but the essentials on which Brown and his family needed to live."

LAST MONTH, several hundred or thousand New Yorkers gathered in that city's Zuccotti Park. Their objections were myriad and that is the point. "Rome wasn't built in a day. It wasn't destroyed in a day either. Don't define anger at myriad problems as lack of focus," wrote Ryan Hoffman, co-author of the Declaration of the Occupation of New York City, on Twitter. The movement has now inhabited parks and squares across America. It looks like an extension of the Arab Spring. The Arab Spring, in turn, looked somehow like an extension of the Iranian election protests. The Iranian protests were probably not an extension of Operation Iraqi Freedom, however, or the uprisings in Lebanon in 2005 that the Bush Administration claimed to inspire, but there is definitely a pattern here: A man who'd had enough set himself on fire. Protesters overthrew a regime in Tunisia. Demonstrators overthrew a dictatorship in Egypt. Pharaohs have ruled Egypt for thousands of years, and now the country has fifty political parties. Occupy Halifax is a different story, but it's exciting that Occupy Nairobi is possible today.

Revolutions begin when someone says no. Albert Camus defined a rebel in just those terms: A rebel is a man who says no. But the revolution begins for real when those who say no proceed despite second thoughts: Perhaps this will not end well. George Orwell said that every revolutionary proceeds with the secret belief that they're going to fail. "Whatever was true now was true from everlasting to everlasting," he wrote in Nineteen Eighty-Four, and yet some revolutionaries proceed still.

Orwell also wrote that, while he was a colonial policeman in Burma, he was all for Burmese self-determination. Then he described shooting an elephant, although he didn't want to, because he was afraid the Burmese would mock him if he refused. Speaking of violence, Orwell also said of Gandhi that saints should be considered guilty until proven innocent, that vanity on Gandhi's part was worth inquiring about, and that the father of modern India might have made an outstanding lawyer or capitalist. But he concluded that, in the end, what matters is what Ghandi achieved.

John Brown died because he took up arms. Maybe the availability of a book about his last stand at the Occupy Wall Street Library is meant to ward us off from his extreme ways. But not all revolutionary moments are created equal. Today, people in the Middle East have changed their world in ways that must have once seemed unimaginable. The Occupy movement consists, in part, of a generation of North Americans who are going to wind up poorer than their parents. This is a significant disruption in the grand narrative of the West; for us, too, the realm of the unimaginable no longer seems so far away. The question is now: will the Occupy movement go the way of Gandhi or Brown? Should it take up arms, or must violent revolution wait until America finally declines for good, and the movement retreats, occupying the remote feral zones of Detroit?

THE HARVARD PSYCHOLOGIST and Montreal native Stephen Pinker recently published an epic study on the history of violence. Pinker argues that, by 1945 to 1950, not only had ethnic and religious violence fallen into decline, but soon after many other kinds of violence would as well. Societies that prize difference descend from those in which states pioneered the monopoly of force, thereby disrupting cyclical violence between different groups.

"In the 17th and 18th centuries England was swept by hundreds of deadly riots targeting Catholics. One response was a piece of legislation that a magistrate would publicly recite to a mob threatening them with execution if they did not immediately disperse. We remember this crowd-control measure in the expression to read them the Riot Act," he writes in The Better Angels of our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. The title is a quote from the last line of Abraham Lincoln's first inaugural speech.

"It's striking that for all the talk about polarization in the US, the Tea Party Movement and Occupy Wall Street are entirely non-violent. Overseas, no one expected the Arab Spring protests to be as nonviolent as they were," Pinker wrote in an email. The threat of overwhelming reprisal from authorities may have brought some peace to seventeenth- and eighteenth-century England, but Pinker also pointed to research that, today, "nonviolent protest movements achieve their aims far more often than violent ones." Still, the story of violence's decline contains much violence, and America is no exception.

"The United States also has a long history of intercommunal violence. In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries just about every religious group came under assault in deadly riots, including Pilgrims, Puritans, Quakers, Catholics, Mormons, and Jews, together with immigrant communities such as Germans, Poles, Italians, Irish, and Chinese," he writes in his book. "[I]ntercommunal violence against some Native American peoples was so complete that it can be placed in the category of genocide." The sharp decline in violence that Pinker notes, beginning after the Second World War, belongs to a much longer trend: "The decline of deadly rioting is part of a millennia-long movement away from violence of all kinds." He argues that, after World War II, states largely stopped going to war against each other. We are now living in what he calls "the long peace." Ethnic and religious violence had already declined by the war's inception, according to Pinker, and for most, after the Cold War, life improved even more.

And yet some questions remain. Would Americans occupying squares in earnest ever take to violence, as some activists did during the 1960s? How does a cause become a movement? How does a movement become a revolution? How does a revolution avoid becoming merely a hobby gone viral?

A friend in New York described the Occupy Wall Street protests as "the kids downtown." He shared a few thoughts on John Brown via a smartphone reply on Facebook:

"oh yes. oh yes.

what a great point of reference.

i went downtown last weekend. was a bit boring. but at least it's keeping up some momentum and giving the kids something to do... politically neutered as it may be.

john brown though. there's no john brown without two things - bankruptcy and the great awakening. we have plenty of broke-ass bible-readers these days, so it remains apropos.

musing over a john brown occupy wall street could last a few bottles of bourbon easy.

the kids downtown aren't fired up with god, so they'll never have the momentum they need. john brown would much more literally occupy wall street. or congress. might need to specify the moral fulcrum of john brown on wall st. what is its "slavery"? certainly lynching lobbyists and dreaming of a great uprising of the 99% is part and parcel, but where would he derive his conviction in the present scenario and in what murderous direction would that send him?

you could also consider his stages. first he was a jacksonian homesteader, then he was an upstate freedom trail guide, then bloody kansas, then harper's ferry, poetry, eternity. an incredible progression. that kind of context could be interesting.

who would john brown kill?

i guess i imagine him viewing national resources, particularly labor and commodities, as being unlawfully pillaged, laying devastation to god's fat dispossessed children. and completely in some liberation jesus mindset, with no hume, hardin or marx on the mental horizon to sully the purity of his bonfire.

this is fun

but i have to go"

JEFF SHARLET, the American writer, recently published a book called Sweet Heaven When I Die. It mentions a dramatic act of self-immolation in Amherst, Massachussetts in the early 1990s that might remind some, at first glance, of what Mohamed Bouaziz did more recently in Tunisia. In an email exchange, Sharlet called the Amherst Common burning a "political 'baptism.'" But few remember Greg Levey, the man who set himself on fire that day to protest the first Gulf War.

In an email, Sharlet wrote that he does not believe John Brown would feel comfortable down at Liberty Park. "I think the better parallel would be the West Coast general strike of 1934, led by Harry Bridges, among others," Sharlet said. "For Bridges, non-violence wasn't a philosophical position but an absolute necessity, since they were facing actual troops. And even so they were mowed down. Cameras are important, but its easy to overstate that importance. 'The whole world' was watching then, too, and that didn't slow down state violence a bit."

Non-violence became the default setting of left protesters in America nevertheless, Sharlet said, while pointing out that he's ambivalent of the "hegemony of nonviolence." Most remember Martin Luther King's message and his words, but the Civil Rights Movement, Sharlet says, probably wasn't as non-violent as we'd like to think. "But the murder of King probably insured that misperception, even as a season of violence followed."

Regardless: "Political imagination is not served by walling off any possibility," Sharlet wrote. "That's probably the key lesson of the thirties, when violence and non-violence so often walked side by side. Is this like then? Possibly. That's all I think anyone can say now, but that's a lot. A lot. Because I don't know of any other American left protest in my lifetime about which one could even say 'maybe.' Certainly it's that big around the world. The question, I suppose, isn't so much whether this could be as big as the thirties—it is—but whether Americans will join in. Right now, they're moving toward doing so, in small but growing numbers." (Sharlet recently started a website called Occupy Writers, in support of the movement.)

Geoff Smith, an emeritus professor of history at Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario, taught a memorable and popular course called "Conspiracy and Dissent in American History" for several decades. He was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize for a book called To Save a Nation, in which he wrote, in part, about radio propagandists stirring up reactionary mobs during moments of crisis like the Great Depression, which should sound familiar to anyone who's heard of Glenn Beck and the Tea Party. Smith also participated in the countercultural movement as a graduate student at Berkeley in the 1960s.

"I've always considered the right more powerful in America than the left, except for periods of economic crisis, especially the 1930s Depression, when capitalism seemed on trial and other systems seemed plausible to Americans," he wrote in an email. "Now we face a similar period, and the references to the Great Awakening and John Brown seem interesting here. So, too, do references to 1968 and its variety of 'springs,' ranging from Prague, to the New Left and counterculture, to the liberation movements that burgeoned for a while in Latin America." All of which involved some violence. "The protest burgeoning now against corporate America fits well within the John Brown story, save Brown's ability to get his hands on weapons and to become a martyr for a holy cause. Who is holy these days?"

Minorities have long been subject to accusations of conspiratorial un-Americanism, but powerful groups also display traits of fringe movements, Smith explained during his course. "What marks a cult is not its beliefs, but its distance from the surrounding society," said Andrew Brown in the Guardian, noting how the once-marginalized Mormon faith has now gone mainstream via Mitt Romney. America produces presidents like Barack Obama and challengers like Mormon multi-millionaire consultants who, despite different backgrounds that are wildly contrary to presidential profiles in the past, share a cult-like distance from the street. Such is this land of the free.

John Brown, a Calvinist, the Khalid Sheikh Mohammed of the anti-slavery movement, would indeed find Zuccotti Park an awkward environment, as Sharlet observed. Even Occupy Wall Street might fail to reconcile a singularity like Brown. To suggest that Occupy requires a catalytic figure is to diminish its essential blandness, however; it's not the fringe movement that someone on Reddit addressed the other week by suggesting that protesters start wearing khakis and polo shirts so that middle America can identify with the movement. Perhaps the existence of amorphous online organizations like Anonymous, which has helped drive Occupy Wall Street, is the real reason that American revolutionaries need not take up arms. And the occupiers themselves are Anonymous Lite, mass-marketing sincere insistence that the time for rebellion has finally arrived.

Many others have tried to shape Occupy Wall Street for their own ends. The Center for American Progress recently "branded" Occupy Wall Street as "The 99% Movement," with flagrant disregard for Adbuster's initial call to arms. (n+1 editor Charles Petersen has described the Center for American Progress as "Obama's think tank" on Twitter.) Al Gore "endorses" Occupy Wall Street. The Bongo Drum Libel persists. These so-called "anarchists" are the new conservatives, while the suits are the new radicals, wrote David Brooks in the New York Times. Novelist Don DeLillo, with whom David Brooks has nothing in common, said something similar in an essay written during the post-911 moment:

"The protesters in Genoa, Prague, Seattle and other cities want to decelerate the global momentum that seemed to be driving unmindfully toward a landscape of consumer-robots and social instability, with the chance of self-determination probably diminishing for most people in most countries. Whatever acts of violence marked the protests, most of the men and women involved tend to be a moderating influence, trying to slow things down, even things out, hold off the white-hot future."

THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION was surprisingly conservative as far as revolutions go; it worried about the future, too. First, Americans revolted against Britain because they feared that liberty in the colonies might be corrupted by British decadence. Later, the Revolution was meant to preserve the status quo. Colonial Americans sought, in other words, to protect their existing rights as Englishmen, according to Bernard Bailyn, a leading scholar on the ideological origins of the American Revolution. They weren't really trying to change the system at first, but rather stop the more powerful from abusing it. Another American historian, Pauline Maier, wrote that "the colonists sought a past that could not be rewon, indeed if it had ever existed." This is from a book called From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain. Nostalgia for a better past that probably never was sometimes turns reformers into revolutionaries; losing innocence is, among Americans, a perennial concern.

The US Constitution's preamble reads: "We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America."

The author of that preamble, a statesman called Gouverneur Morris, also wrote the following, in a 1774 letter complaining that a British crackdown on colonial discontent might disenfranchise the emerging American aristocracy to which he belonged: "The mob begin to think and to reason. Poor reptiles! it is with them a vernal morning; they are struggling to cast off their winter's slough, they bask in the sunshine, and ere noon they will bite, depend upon it. The gentry begin to fear this."

THIS LEADERLESS OCCUPY MOVEMENT has produced spokespeople. While the Declaration of the Occupation of New York City addresses a variety of concerns, and even includes an asterisk to indicate that its list of grievances is non-inclusive, Ryan Hoffman said the bailouts in particular made him angry. In America, businesses are supposed to fail, because America is competitive. Something's happening because something has changed.

Following Hoffman from his Twitter account to his website reveals that, just as the founding fathers of America were lawyers and planters rather than "fringe" radicals, Hoffman is not a professional activist but rather an actor and writer. Among many other questions asked of Hoffman, during which he said that the Occupy movement has little in common with the Arab Spring because very few Americans have personally experienced the hardship of life in the Middle East, this was the last:

"It's you and a banker. You have proof of fraud. No law. No cameras. Do you punch him in the face?"

In 2001, Delillo made this observation about the terrorists: "We are rich, privileged and strong, but they are willing to die." We know that much was true of John Brown, at least, even if we don't know whom he would kill.

"No Comment," Hoffman wrote back, in what seemed like a winning answer.

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—Why Occupy Wall Street Has Already Succeeded

—Martyrdom and 9/11

—Big Brother Likes This