Muammar Gaddafi Died Special

We were used to laughing at him. But there was something pitiable and human in Gaddafi's final, bloody moments.

MUAMMAR GADDAFI died special. He died unlike any other dictator in the history of the world has, so far, in part because a prelude to his execution appeared online, in which unidentified Libyans beat him bloody on some shitty desert street, in the bright sunshine, in front of what became a global audience. In March, a premature obituary indulged the colonel by cataloguing his eccentricities: "We may see another Libya...but there will never be another Muammar Gaddafi." Overlooked so far, during this mass social-media post-mortem, is that Gaddafi had made a promise: he swore that he would fight to the very end. He did that, for the most part, except perhaps during those final hours off-camera, so far undescribed.

On October 20, Libya's rebels found Gaddafi cowering inside a concrete drainpipe under a road in his hometown of Sirte, carrying an obligatory golden pistol. This in the country he had ruled for forty-two years. The mob included kids with cell phones and Kalashnikovs. Had Gaddafi ever stopped to envision the beginning of the end, the reality show we had all been waiting for? NATO forces intervened eight months ago to protect Libyan civilians from Gaddafi, during an uprising from Benghazi against his rule. This city produced a disproportionate number of foreign fighters in Iraq during the American occupation, so when they saw what was happening in Tunisia, the people of Benghazi knew what to do.

The elites of Tripoli now live in fear of imams and teenagers with machine guns. But Gaddafi's death is how the fight for Libya was resolved. For once, the man did not amuse. People get swarmed and beaten every day just like he did, all over the world, even in the West. The individual who was the state comes to know the individualism of the powerless, which is to say, he comes to know loneliness. But the whole narrative of Gaddafi's death is still obscured. This clip, billed as the clearest video so far, sheds some light. Libya's Freedom Group produced it, but even Gawker posted it, too.

On October 22, Human Rights Watch released a video that talks about this brutal scene in Sirte, adding questions like: Who put the bullet in Gaddafi's brain? Where and how? The Western-backed Transitional National Council, which transcended Gaddafi as he went into hiding and has now inherited his state, claims that he died in a shootout, caught in the crossfire. But Human Rights Watch, making the obvious point that Gaddafi was still alive while in captivity, disagrees. "He was not mortally wounded when he was taken away from the place of his capture and left the city of Sirte," said HRW's Emergencies Director Peter Bouckaert, "so something happened after his capture and his arrival in Misrata, dead."

MUAMMAR GADDAFI was sixty-nine years old. He did not die like Saddam Hussein, his contemporary and fellow victim of regime change. In Egypt, Hosni Muburak faces prosecution, but the country is still subject to emergency law. In Damascus, Bashar Assad likewise must contemplate the inevitability of the end. Since Assad was an opthamologist in London and president of the Syrian Computer Society, he is likely, on some level, a rational human being. Exile might look appealing right now. His beautiful wife appeared in a fashion magazine on the eve of a revolution that its editors failed to predict. But just because autocrats quit in Tunisia and Egypt doesn't mean Assad will do the same. To walk away from an inherited presidency means acknowledging not what he stands to gain by leaving, but what he stands to lose by staying.

On October 23, nine-tenths of Tunisia voted in free elections. The winning party will probably have Islamist leanings. Ethnic and religious demography gain new importance when Middle Eastern "socialists"—like Gaddafi and Saddam—leave the scene, replaced by elected officials. Gaddafi once declared himself the leader of the Third World; Libya has oil, and the country bridges Africa and the Middle East. Saddam, meanwhile, aspired to make Iraq the leading Arab nation, perhaps even the "shield of the Arabs" against Iran. But Sunni, Baathist Saddam succumbed to demography, too. He spent his final minutes in a dark, unceremonious ministry room among Shia gangsters. They wore leather jackets and balaclavas, and arranged a noose around his neck on behalf of Iraq's Shia majority. At least one executioner used a cellphone camera.

They killed Saddam on an Islamic holiday, Eid ul-Adha, which many international observers thought was crude; the holiday is typically more popular with Sunni Muslims. One reaction to his demise stands out. An outlet called the Exiled Online, originally founded by Matt Taibbi and Mark Ames in Moscow after the fall of communism, has a writer pseudonymously named Gary Brecher. He wrote about Saddam's death in a column called "Saddam Died Beautiful." Saddam wore a suit and dark overcoat to his execution, like he was attending someone else's funeral. He mocked their imam, Moqtada al-Sadr. In the seconds before the platform dropped, his prayers quickened just a bit, according to the video. His own jails treated others much worse. But Saddam died like a man, in old-school fashion, demonstrating withering contempt and blustering certainty that his country needed him to survive.

Gaddafi, on the other hand, gets bloodier by the second. "Don't shoot! Don't shoot!" he cries. He stumbles around like someone gone suddenly blind. He asks for more time. A man who was untouchable for most of his life appears confused, even pitiable. His eccentric hairstyle remains, rather matted now, as the camera trains on his face: Gaddafi is still in there, somewhere. You can tell. But at some point along the way he died, even before he took a bullet to the brain.

We don't know much about how he was tortured beforehand; he was allegedly, at one point, anally assaulted with a weapon. We probably won't learn all there is to know about the desecration of his corpse. On Monday afternoon, Gaddafi's body could be found on a slab in former onion freezer in a Misrata supermarket, strategically posed to shield certain wounds from view, as putrefaction took its course. Curiosity brought average Libyans to the freezer for Gaddafi's one and only state funeral. More than fifty Gaddafi loyalists, meanwhile, were discovered dead on the lawn of an abandoned hotel during those early days of liberation.

A British Middle East analyst and Libya expert named Alex Warren said this on Twitter: "Gaddafi's death was much like his rule. Deeply eccentric, unpredictable, bloody, captivating, and above all confused." Elsewhere he wrote, about the day Gaddafi died: "The people in charge yesterday were militia fighters with no visible sign of a meaningful command structure and largely free to take matters into their own hands. Decision-making was informal and disorganized—with audible arguments over whether to bring Gadaffi in 'alive or dead' at his moment of capture—and although many Libyans welcomed his death, others were also keen to see him held accountable in the dock."

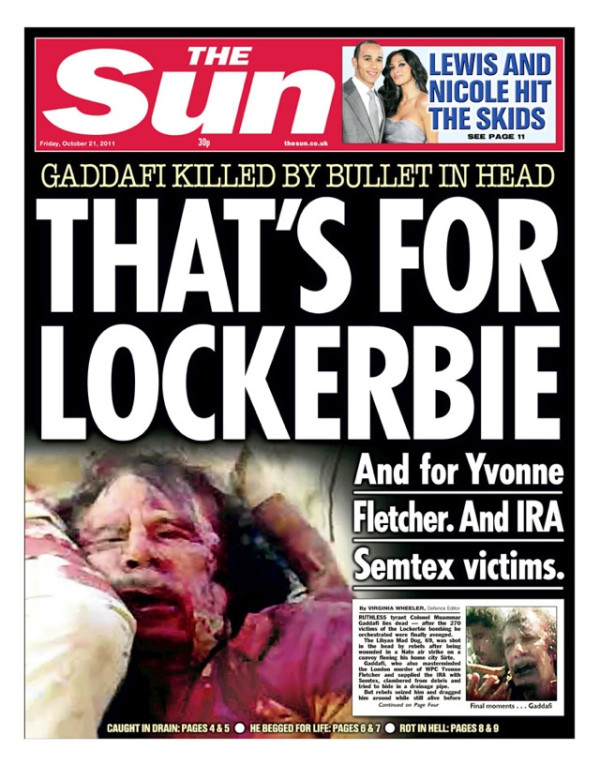

Fragments of Gaddafi's capture are documented. They will live forever. But the future is impossible to predict. A local military commander in the city of Misrata, where fighters took Gaddafi after the initial rendezvous in Sirte, said "over-enthusiastic" fighters seized the moment when Gaddafi was captured. The military commander did not say much, but at least this sounds true: "We wanted to keep him alive, but the young guys, things went out of control," he said. The Sun, a tabloid in the United Kingdom, seemed all right with that result, and said so on the next day's front page. Foreign Policy magazine also showed graphic images. Everyone seems to know that shit was crazy.

The Russian reaction to Gaddafi's death represents a dissenting view. Did NATO forces block Gaddafi's escape route, then set the fighters up to finish things their own way? "Attacking targets on the ground has nothing to do with enforcing a no-fly zone ... especially if they are not attacking anyone but trying to escape," said Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, who wants a UN investigation into Gaddafi's death. Some Russians went beyond condemning the circumstances of Gaddafi's execution. Vladimir Zhirinovsky, an ultranationalist and the leader of the Liberal Democratic Party, compared Gaddafi to the founders of communism and the Italian nation-state on his blog: "He is the wisest of men, an African Karl Marx, a Libyan Garibaldi."

Said Vladimir Putin: "Nearly the entire Gaddafi family was killed. His corpse was shown on all world TV channels. It's impossible to look at it without disgust!" Even Barack Obama told Jay Leno that, sometimes, decorum should prevail. "That's not something that I think we should relish," the president said on the Tonight Show.

Two years ago, Gaddafi arrived in New York City and delivered an epic speech before the United Nations. Along with other world leaders, he sat for a New Yorker portfolio. Photographer Platon recently described the encounter in a piece called, predictably, "The Craziest Guy in the Room": "He was vacant. There was no emotion, there was no spirit. It was void of something. When you come face to face with that it's overwhelming, and that's what I was trying to get in the picture." He also noticed a copy of Gaddafi's speech. "It was written in red crayon, in giant letters, like a six-year-old kid would write it. And it was written on about twenty pieces of tatty paper torn out of a book, in Arabic. It felt like notes of a madman."

IT IS UNCLEAR whether Gaddafi's thesis, the Green Book, will live on forever, like Che posters have. Mao pins are still around, along with the Chairman's Red Book. When I went to Iraq following the American invasion, I got some currency with Saddam on it and gave it all away at Christmas. I also have a copy of Castro's "History Will Absolve Me." But will Gaddafi live on in some kind of posthumous brand? He certainly had the money to turn himself into an icon: the Los Angeles Times reported that he was perhaps the richest man in the world, estimating his fortune at $200 billion.

On October 22, Mustafa Abdel Jalili, leader of the Transitional National Council, officially declared that Libya had been liberated, before saying a few words about the future: "We are an Islamic country...We take the Islamic religion as the core of our new government. The constitution will be based on our Islamic religion." Libya's elections are scheduled for eight months from now. It all has a familiar ring: "Coup ousts King; junta seizes Libya: Socialist State Proclaimed." That was Gaddafi's doing in 1969.

Human Rights Watch is concerned about the circumstances under which Gaddafi died. But the organization says that its concerns go beyond the events of that day. "It's also about armed groups operating with impunity in Libya," said Peter Bouckaert. Summarizes one Gulf newspaper: "Tripoli has become a patchwork of armed fiefdoms, as wannabe power brokers backed by hometown militias battle with each other and with natives of Tripoli for the spoils of war, a slice of the country's wealth and a share of political power."

So it begins. On the afternoon of October 24, an unnamed official with the National Transitional Council quietly announced that a simple burial would take place for Gaddafi somewhere in the desert, and that the "corpse cannot last longer." Gaddafi gets an anonymous grave so that it does not become a shrine. Here he is again in more images, never seen before, many of them taken with his family, or with other North African leaders. They make you wonder what happened to the guy along the way. Indeed, he looked so young once. Did power change him, or was he always this way?

Those who lynched Muammar Gaddafi showed that we are animals. Sometimes the propensity to judge increases with proximity from the act, but I don't intend to cast any moral aspersions here. What would you have done? You would have beaten this man bloody too, no? Whoever put the bullet in Gaddafi's brain can dine out on that story forever. As his city lay in ruins, Gaddafi was writing and making tea, according to one loyalist. Another, his rather humble-looking driver, said when the rebels closed in, Gaddafi didn't know what to do. Unlike Saddam, Gaddafi did not die beautiful. But who really does? Rather, in those last, lonely moments, Gaddafi learned what it means to be afraid, and so maybe he finally learned what it means to be human, too.

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—Being Muammar Gaddafi

—Iraq's Walking Dead

—Should Occupy Wall Street Take Up Arms?