Bad Habits

The strange confluence of nun pornography and anti-Catholic propaganda.

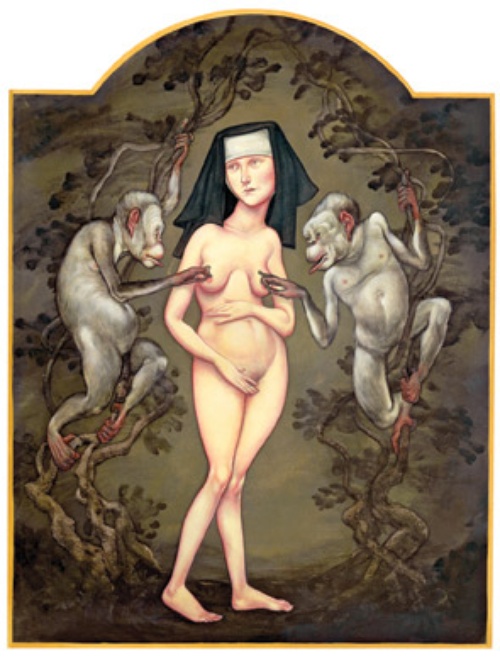

Illustration by Anita Kunz.

In the early 1800s, a young Protestant woman named Maria Monk joined a Catholic convent called the Hôtel Dieu, on Montreal’s St. Paul Street. “I had a high idea of life in a Convent,” she later wrote, “secluded, as I supposed the inmates to be, from the world and all its evil influences, and assured of everlasting happiness in heaven.” But the reality of convent life was quite different. After Monk’s initiation, the Mother Superior told her that “one of my great duties was, to obey the priests in all things; and this I soon learnt, to my utter astonishment and horror, was to live in the practice of criminal intercourse with them.” Like the other “Black nuns” of the Hôtel Dieu, she became a sex slave, forced to satiate the erotic appetites of the priests of a nearby seminary, who entered the convent through a secret tunnel. The infants resulting from this “criminal intercourse” were baptised, strangled and disposed of in a lime pit in the cellar. Monk eventually escaped, preventing the murder of her unborn child.

Or so goes her story, which was published in 1836 as The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk. The problem: it was almost certainly made up, designed to capture the anti-Catholic zeitgeist of nineteenth-century America. Four years earlier, a Protestant charity pupil named Rebecca Reed had run away from an Ursuline nunnery in Massachusetts. Reed’s claims of abuse by the nuns there contributed to a wave of violence against Catholics in Boston, which climaxed when a mob torched the convent. Reed’s runaway bestseller Six Months in a Convent, or, the Narrative of Rebecca Theresa Reed was published to capitalize on the incident.

The success of Reed’s account undoubtedly contributed to the later popularity of Awful Disclosures. But while Reed’s account was relatively plausible, Monk’s was an absurd porno-Gothic fantasy. Monk claimed that she and the other nuns were bound, gagged, kept in tiny cells and forced to whip themselves. She was also made to wear spiked belts and a leather cap that somehow induced pain, which “was hardly put on my head before a violent and indescribable sensation began, like that of a blister, only much more insupportable; and this continued until it was removed.” These physical ordeals were not depicted as self-flagellating expressions of Christian devotion, but as evidence of the sadism of a fundamentally perverse religion: Catholicism.

Monk’s real life was more pathetic than Gothic. According to Monk’s mother, her forehead was punctured by a slate pencil when she was a child, making her prone to fabrication; in fact, she had never even been in the Hôtel Dieu convent. Instead, she had stayed in Montreal’s Catholic Magdalene asylum for the reform of prostitutes. As Nancy Lusignan Schultz writes in her book Veil of Fear, Monk probably concocted this fantastic story to arouse the sympathies—and the passions—of her sex-work clients. Even the anti-Catholic Quarterly Christian Spectator wrote, in 1837, “If the natural history of ‘Gullibility’ is ever written, the imposture of Maria Monk must hold a prominent place in its pages.”

Nonetheless, people believed her. Monk and her guardian, the Reverend William K. Hoyte, arrived in New York in 1835, where her story was transcribed—or, more likely, ghostwritten. By 1860, the book would sell some three hundred thousand copies. Monk herself, called “the frail nun” by James Fenimore Cooper, enjoyed brief celebrity, socializing with Nathaniel Hawthorne and Samuel Morse. But she saw little money from the literary phenomenon that bore her name, and died alone in a New York prison in 1849.

Nothing grabs the public’s attention like a woman in danger, and the story of Maria Monk occupies a murky area where propaganda shades into pornography. Nuns are particularly well-suited for this; they are removed from women’s supposedly natural place in the home and subjected to the unnatural sexual regime of the convent, under the authority of celibate priests instead of fathers and husbands. Nuns have often been depicted as either lesbians or passive sexual playthings, as Frances E. Dolan writes in her 2007 article “Why Are Nuns Funny?” One influential pamphlet from 1622, Thomas Robinson’s The Anatomy of the English Nunnery at Lisbon in Portugall, claimed that the convent’s nuns were helpless to resist clerics: “not one amongst them will (for feare of being disobedient) refuse to come to his bed whensoever he commands them.”

Such tropes aren’t limited to nuns. There’s a long tradition of literature linking the Catholic Church with sexual deviance; Boccaccio’s Decameron, from the mid-fourteenth century, included tales of lecherous clerics and randy nuns. Even in predominantly Catholic countries, clergy were frequently the subject of prurient interest. In eighteenth-century France, the scandalous affair between Jesuit priest Jean-Baptiste Girard and his penitent Mary-Catherine Cadière led to a sensational trial. The court reports employed the sexually charged language of seduction and surrender, with Girard apparently demanding of Cadière, “Will you not yield yourself up to me?” These themes were later used in novels and pamphlets loosely based on the case—some philosophical, some pornographic, some both; characters named after anagrams of “Girard” and “Cadière” appeared in the 1748 novel Thérèse Philosophe, which combined flagellation erotica with materialist philosophy.

Across the English Channel, publishers printed cheap pamphlets documenting the trials of French priests like Girard, slanted to suit English anti-Catholic prejudice. To the post-Reformation English, Catholicism was an exotic and threatening Other, symbolized by ignorant, oppressed nuns. The English used religious and sexual transgression as metaphors for each other, as in Matthew Lewis’ The Monk (1796), which depicts a man seduced by a fellow monk—who turns out to be the devil disguised as a woman. In Ann Radcliffe’s The Italian (1797), the heroine is forced to choose between marriage to an evil man or life as a nun in a cruel Catholic order.

The US, in turn, inherited England’s anti-clerical media through books pirated across the Atlantic. American publishers reflected their own nativist cultural anxieties about new immigrants and their strange customs—especially Catholics. This led to the success of Reed’s and Monk’s convent tales, which combined sex, violence and xenophobia. As Richard Hofstadter writes in his classic essay “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” “Anti-Catholicism has always been the pornography of the Puritan.”

Over the decades, as Catholics integrated into American society, the idea of convents as hotbeds of sex and abuse lost its propagandistic edge. Instead, in the US’s growing domestic erotica industry, nuns came to symbolize clandestine sexual escapism. In the 1870s, catalogues of erotic books published in New York included titles like “SCENES IN A NUNNERY. Very plain words. 25 cents” and “SILAS SHOVEWELL, His Amours with the Nuns, 10 colored plates $2.00.” In a profane parody of religious devotion, the nun in her habit retained an erotic charge long after social anxieties about Catholicism changed, just as the maid, in her black dress and white apron, remained fetishized even after domestic servants were no longer ubiquitous.

Today, Islam is the West’s exotic, threatening Other. The supposedly inferior status of Muslim women is used to indict Islam as tyrannical and sexually perverse, with much emphasis placed on practices like polygamy and veiling. The flipside of this propaganda, of course, is sexual fantasy. A website called Tales of the Veils collects pictures and amateur erotica depicting women in burkas; sometimes, they wear bondage gear under their veils. In one story, a character tells his captive wife, “There are two reasons why one should restrict and control a wife. One is very virtuous and holy indeed.” But the other, non-religious reason is less honourable: “Some men like to see suffering, to force unwilling girls into bondage, to rob them of their dignity and freedoms and turn them into items of bondage, lovetoys as it were. Some men are very sick, sick like that.”