The Abattoir's Dilemma

Small slaughterhouses are a crucial link in the farm-to-fork chain. But in Ontario, excessive regulation is putting them out of business.

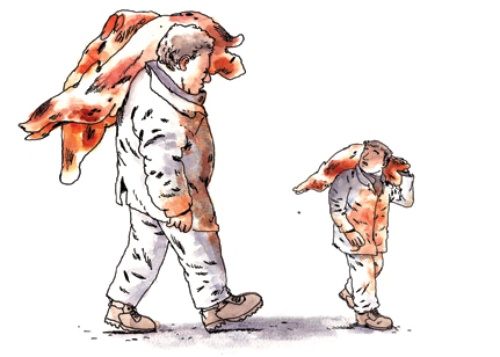

Illustration by Victor Kerlow.

In the killing room at Town & Country Meats, glittering hooks hang from the ceiling. A stainless-steel machine sits idle in the corner—inside, an ominous row of rubber teeth waits for the chance to raze a hog clean. But not one pig has been de-haired here since August 2011, when owner Rob Koldyk decided to stop slaughtering animals. His family had been in the business for generations, but by the summer of 2011, he was financially and emotionally exhausted by the constant renovations required to maintain his operating licence.

“You just can’t survive,” Koldyk says bitterly when I ask him why he closed up shop. For the last two years, he and other abattoir operators have lobbied to change how their facilities are regulated. “I was tired of fighting, tired of getting nowhere, tired of spending money.”

Koldyk’s story is not unusual. In 1998, there were 267 abattoirs in Ontario. By last spring, only 142 were still licenced. In the intervening years, the Food Inspection Branch of the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs—the provincial body that regulates both freestanding meat plants, which process slaughtered carcasses, and abattoirs—ratcheted up enforcement, exacerbating problems that already plagued small operators.

The push for stronger rules stemmed from an incident in 2003, when investigators discovered that Aylmer Meat Packers was processing already-dead animals for human consumption. The grisly revelations resulted in a media frenzy and called Ontario’s meat-inspection system into question.

While every abattoir owner I spoke with said that food safety is crucial, many added that OMAFRA’s new regulations focus more on the perception of safety than on safety itself. Of the abattoirs that are still licenced, it’s hard to determine exactly how many are actually slaughtering. Some owners, like Koldyk, have stopped killing, but are hanging onto their licences in the hope that they’ll be able to sell their businesses. Others have moved from both killing and processing to processing only, because it’s subject to fewer regulations. Since abattoirs, unlike large slaughterhouses, usually serve small communities of nearby farmers, such closures make local meat harder to come by.

Over the course of reporting this story, I called every licenced abattoir in the province. About a dozen were dead lines; of those I reached, I heard the same thing over and over: We’re still in business—for now.

Since 2009, Louis Roesch has been trying to change the way Ontario’s abattoirs are regulated. He and his wife Clara have a hog farm and a freestanding meat plant in Chatham-Kent, both of which depend on abattoirs to function. (The meat products they process come from animals that are slaughtered in abattoirs.) That year, meat plants became subject to OMAFRA rules, and, around the same time, regulations concerning abattoirs also became more strictly enforced, with heightened supervision and inspection by provincial employees. These changes followed the recommendations of Justice Roland J. Haines, who was appointed by the government to evaluate the Ontario meat industry in 2004, in the wake of the Aylmer incident.

Over a fresh pork roast, Roesch explains that he spearheaded an ad hoc committee, called Concerned Abattoir and Stand Alone Meat Operators of Ontario, which is lobbying for changes to three main areas. The committee says that abattoirs are bogged down by OMAFRA’s renovation requirements, which Roesch claims are more cosmetic than substantive. For example, in dry storage areas, owners are required to replace wooden surfaces with stainless steel or plastic, even though these areas never come in contact with meat. Provincial inspectors have also taken issue with display cases in which sealed, ready-to-eat products rest on painted metal surfaces rather than stainless steel, and have quibbled about the type of wall paneling in office spaces. “A lot of the stuff that they’re pushing for is not even about safety,” says Al Babcock of Dresden Meat Packers.

Excessive paperwork is another common complaint. “I used to cut meat all the time,” says Mark Clark, the owner of Highgate Tender Meats. Now he does paperwork for two to three hours each day. He adds that OMAFRA requirements are tailored to large plants with hundreds of employees, rather than mom-and-pop operations where the same few people manage all aspects of the business.

Most frustratingly, abattoir owners say, enforcement of these rules is erratic and varies widely, depending on different inspectors’ opinions. Babcock says that last year, for the first time, an auditor raised concerns about the type of padding on pens and the type of latches on gates. This was one of four different auditors Dresden Meat Packers has had since 2009. “That’s four different people’s outlook of what our business should be,” says Babcock. “You’re working on changing one thing, and then for the next guy it’s not an issue, but something else is.” In addition to these audits, an inspector must always be present when animals are killed, and other activities like processing and retail are subject to weekly check-ins. It’s not unusual for Babcock to see up to three inspectors each week. “It’s burning away your daylight,” he says.

In a 2010 survey of abattoir owners conducted by the committee and distributed by the Ontario Federation of Agriculture, 91 percent of respondents felt that some regulations forced them to invest in cosmetic renovations. Ninety-three percent said they felt overwhelmed by paperwork. And 74 percent said they did not receive enough information to prepare for new or upcoming regulations.

If the committee’s complaints aren’t addressed, Roesch doesn’t think there will be any small abattoirs left in five years. “Some people have these conspiracy theories that OMAFRA is trying to wipe out small businesses,” says Freeman Boyd, Local Food Project Coordinator of Foodlink Grey Bruce, an initiative that supports farmers and promotes local food. “I don’t think that’s the intention, but it will be the effect.”

Industrially processed meat, like anything made in a large factory, is an anonymous product. All meat begins its life on a farm somewhere. But when most livestock is ready to be slaughtered, it’s loaded onto trucks and shipped to market, where it’s auctioned off, often to large food corporations. The animals are then trucked to industrial plants that operate around the clock, processing thousands of carcasses a day. Because these larger plants are federally regulated, their products can be sold inter-provincially and internationally. Meat that originated in Ontario will often end up on a supermarket shelf thousands of miles away.

This is a stark contrast to livestock slaughtered in a small abattoir. An abattoir generally services its surrounding community, and meat killed in small abattoirs has to be sold within the province, meaning that it’s far more likely to be local. Abattoirs typically slaughter animals only one or two days a week, and their flexibility helps them meet the needs of niche markets. Organic, free-range and specialty meats depend on the abattoir system.

“You have to have people on the small end or you just don’t have local food,” says Grant Robertson, who raises organic cattle in Bruce County and sells meat to specialty shops, restaurants and directly to consumers. He’s worried about the future of abattoirs in Ontario too. “We don’t want them subject to a whole red-tape regime that isn’t really about food safety.”

Owners’ concerns about overregulation have been met with “limited receptiveness” at OMAFRA, according to Bob Jantzi, who runs a freestanding meat plant and is part of Roesch’s committee. “OMAFRA sees food safety as a conversation ender,” adds Boyd. The discussion shouldn’t just be about ensuring that food is safe, he says. Provincial regulations should also aim for food that is affordable, nutritious and local.

But OMAFRA Senior Communications Advisor Susan Murray is reluctant to imagine an alternative to the current system. “Food safety has to be the priority,” she says. “We can’t apologize for regulations that increase the safety in the province.”

OMAFRA Food Inspection Director Rena Hubers also defends the regulations, and says that providing support for local and organic food falls under the purview of the ministry’s economic-development division. She suggests that the increase in abattoir closures merely reflects decreased demand for their services. According to Statistics Canada’s numbers, though, total heads of livestock (cattle, hogs and sheep combined) decreased by 12 percent in Ontario between 1998 and 2011. Over the same period, the number of abattoirs decreased by more than triple that rate: 47 percent.

Abattoir operators have some ideas for changing the system. Some regulatory exemptions are already in place for situations in which there is direct contact between the producer and the consumer—at farmers’ markets and butcher’s shops, for instance. This precedent could allow small abattoirs and meat plants to provide the direct, farm-to-fork experience more and more consumers crave. “We need to make sure these businesses are supported,” says Robertson. “They provide some of the safest food in the entire world and they do so right on our doorstep.”