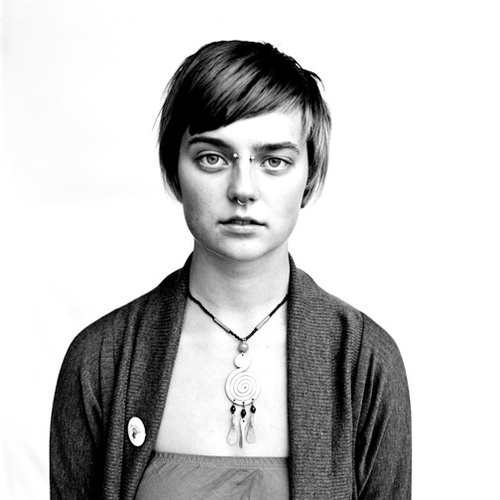

Brett Gundlock’s “Prisoners” project documents people detained during the 2010 G20 summit and collects statements on their experiences.

Photograph by Brett Gundlock.

Brett Gundlock’s “Prisoners” project documents people detained during the 2010 G20 summit and collects statements on their experiences.

Photograph by Brett Gundlock.

Unmasked

Searching for lessons in Toronto's 2010 G20 debacle.

From June 26 to 27, 2010, world leaders from Canada, the US, the European Union, the International Monetary Fund and a host of other nations and organizations met at the Metro Toronto Convention Centre to discuss the global recession, financial regulation and the eurozone crisis. The 2010 G20 summit in Toronto, like its predecessors in cities such as Pittsburgh and London, attracted protests from a broad coalition of social-justice groups. A handful of demonstrators smashed windows and set police cruisers on fire, and more than one thousand people were detained, resulting in widespread accusations of police abuse.

Toronto-based activist Alex Hundert refers to the G20 as a “very real embodiment of contemporary globalized neo-liberal capitalism” and says that he “felt both compelled and responsible to organize against the G20 summit when it came to town.” He writes to me from prison; he was one of seventeen people referred to by the Crown as a member of the “G20 Main Conspiracy Group,” allegedly responsible for encouraging property destruction. Hundert was arrested at gunpoint early on the morning of June 26, before he’d had the chance to protest at all.

Others arrested before the demonstrations began include prominent community organizers like Mandy Hiscocks of Guelph, Leah Henderson of Toronto and Pat Cadorette of Montreal, as well as activists from Kitchener-Waterloo and other cities. Facing conspiracy charges, the group agreed, in November 2011, to a deal in which six people plead guilty to charges of counselling to commit mischief, while the eleven remaining defendants had their charges withdrawn. Their arrests, charges and prosecutions came as the result of an extensive undercover police investigation.

Canada has a long, shady history of police infiltration. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police was originally responsible for security intelligence in Canada, particularly after World War I, when it focused on “labour unrest, anarchism, and the growth of communism,” according to a Library of Parliament article. Many of its surveillance powers were handed over to the Canadian Security Intelligence Service in 1984, when a government commission confirmed that the RCMP had, after the Front de libération du Québec crisis in 1970, “embarked on an extensive campaign of intelligence-gathering, infiltration, harassment and disruption directed at virtually all stripes of nationalist sentiment in Quebec.” The RCMP’s most flagrant breaches of the law included burning down a barn to prevent a nationalist meeting and breaking into the offices of a left-wing news agency in Montreal to steal and destroy files.

But such overreaches are not confined to history, and, by all indications, contemporary Canadian policing seems to follow in the footsteps of the tactics used in the lead-up to the G20. In February 2012, Public Safety Minister Vic Toews released a document called “Building Resilience Against Terrorism: Canada’s Counter-Terrorism Strategy.” It places animal-rights, environmental and anti-capitalist groups alongside white supremacists as domestic terrorist threats, asserting that “continued vigilance is essential since it remains possible that certain groups—or even a lone individual—could choose to adopt a more violent, terrorist strategy to achieve their desired results.” In January 2012, Minister of Natural Resources Joe Oliver wrote an open letter decrying “environmental and other radical groups” that “threaten to hijack our regulatory system to achieve their radical ideological agenda”—groups that, in other words, were using democratic channels to oppose the controversial Northern Gateway Pipeline. A few months later, in June, the Harper government announced the creation of a new counter-terrorism unit in Alberta, citing “a strong economy supported by the province’s natural resources and the need to protect critical infrastructure.” Abby Deshman, director of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association’s Public Safety Program, says that “there’s no increased terrorism threat in Alberta specifically,” and that the CCLA is “worried about investigations into groups without concrete evidence that these groups are going to be violent, or engaged in illegal activity.”

The past year has brought a wave of new developments and revelations regarding Toronto’s G20 debacle. People like Hiscocks and Hundert were finally sentenced to prison terms, and a swath of post-G20 papers, like the May 2012 RCMP and Ontario Provincial Police watchdog reports, were released. As the Harper government and Canada’s police bodies intensify their surveillance of environmental activists, now is the time to root through the wreckage of the G20 policing strategy.

Guelph, Ontario is home to one of the first organic waste processing facilities in North America. In the winter, residents organize to create outdoor ice rinks in the city’s network of small parks. There’s a civic museum, an art gallery, a church modelled after the Notre Dame Cathedral and a vibrant downtown populated by locally owned coffee shops, bookstores, restaurants—even an independent cinema.

Guelph was also home, in the lead-up to the G20 summit, to a branch of one of the largest undercover police operations in Canadian history. The $676 million security bill for the G20 summit and its G8 counterpart—which was held on June 25 and 26 in Huntsville, Ontario—included funding for an eighteen-month-long infiltration of activist communities, from January 2009 through June 2010. The Joint Intelligence Group, a well-staffed network of OPP and RCMP officers based in Barrie, Ontario, carried out this investigation. According to the JIG Operational Plan, the effort included twelve “trained covered investigators,” as well as commanders, managers, and technical and office support. Over the course of those eighteen months, JIG made $8 million worth of capital purchases and had a $297 million operational budget. It set up commander offices, a project room, workstations—and, during the G20 summit itself, an operational “War Room.”

When JIG launched its G20 investigations, a pair of undercover officers named Brenda Carey and Bindo Showan made their first appearances in Guelph. Carey and Showan were two of JIG’s twelve “trained covered investigators.” Every hour they spent on the job was buoyed by the efforts of their handlers, their on-site support team and dozens of office staff and managers, who processed thousands of pages of reports about the comings and goings, the tastes and preferences, the relationships and conflicts of activists under surveillance.

To get to the second floor of the university centre at the University of Guelph, you climb a flight of stairs bordering a multi-level, carpeted seating area. Students read Adorno, or Cosmo; eat quinoa out of mason jars, or stab plastic forks into stir-fried noodles from the cafeteria. Some people nap, using their hoodies and backpacks as pillows. Once you get to the second floor, you can visit the student-union office, say hello to the ever-present gamers or head to the office of the Peak, an alternative magazine that Mandy Hiscocks has been involved with for years. (She recently helped pull together its summer “Dispatches from Ontario Prisons” issue while serving time in the Vanier Centre for Women.)

The university centre is where former Guelph Union of Tenants and Supporters member Josh Gilbert first met Brenda Carey. Gilbert was facilitating a recruitment session for GUTS in April 2009 when Carey—who is 5’3”, petite and had a bleach-blonde pixie cut at the time—arrived. She used the alias “Brenda Dougherty” and described herself as a mature student. “Almost immediately,” Gilbert says, “it came out that she was leaving an abusive relationship in England. She told me that there was money from a settlement that was allowing her to study and be at school.”

Gilbert says he initially thought of her as a keener and a nice, friendly person. Fellow former GUTS member Zach O’Connor describes her manner as gentle. It wasn’t until much later that Gilbert and O’Connor found out that Carey arrived in Guelph in 2009 with a target list of over twenty individuals—activists that she was tasked with befriending and surveilling. “There were thousands of pages of notes, just about every conversation we ever had,” Gilbert says, referring to documentation that came out in court disclosures during preliminary hearings in fall 2011. “Everything I remember—and some things I don’t—were in there.”

After Carey met Gilbert, she joined GUTS. (Full disclosure: when I lived in Guelph, I was a member of GUTS from 2005 to 2008.) GUTS used to drag wagons full of food downtown, to the corner of Wyndham and MacDonnell, setting up outside of the Legal Clinic. Carey, who helped dumpster dive and prepare vegan meals, also pitched in by driving the dinners downtown. “She had this grey Honda,” Gilbert says. “She was really into PETA and animal-rights stuff. She always had stuffed animals in her car.”

Hiscocks and Leah Henderson (who also spent time at Vanier on charges stemming from anti-G20 organizing) both corroborate Gilbert’s description of Carey. In a letter from prison, Hiscocks describes Carey as “very reliable and eager to help—characteristic of infiltrators but also of people who are new.” Over the phone, days after she leaves Vanier, Henderson says she thought of Carey as her “ally” in meeting spaces, “willing to take notes and help out with tasks.”

Guelph was likely chosen for JIG infiltration because of a few arsons that occurred in 2005 and 2006. In 2005, the pro shop of a golf and country club called the Cutten Club was torched; someone also set fire to a Zellers, and lobbed what police described as a Molotov cocktail at the doors of the Church of Our Lady. “ELF”—short for “Earth Liberation Front”—was spray-painted on a walkway at the Cutten Club, and again at the Zellers, this time accompanied by a message: “no more development.” In 2001, the FBI deemed the ELF the “top domestic terror threat” in the US. A 2006 Guelph Mercury article quotes Barbara Campion, a spokesperson for CSIS, who says “it’s a smaller community, so you would never think Guelph would be a hotbed of radical activity.” The article also states that CSIS “partners with local police to investigate eco-terrorism,” though Campion “couldn’t reveal which groups the service is currently looking at.” No one has been charged or implicated in the arsons—Sergeant Douglas Pflug of the Guelph Police Service says the department can’t comment on the investigation, which is “still ongoing,” and my calls to CSIS went unreturned. But environmental activism was one of JIG’s primary concerns.

In 2009, a group of people began meeting to fight the development of the Hanlon Creek Business Park in the south end of Guelph. Calling itself LIMITS—Land Is More Important Than Sprawl—the group identified the business-park site as a provincially significant wetland complex. Matt Soltys says that one of the group’s aims was to reach out to the community and create a broader base of support.

When “Khalid Mohamed,” a man who claimed to be thirty-five (and who appears, in photos published online, to have a soul patch), showed up to a meeting in January 2009, he was one of a handful of people whom organizers didn’t recognize from environmentalist circles in Guelph. Soltys did, however, find some of the newcomer’s behaviour suspicious. For one, Mohamed, who was later identified as Bindo Showan, singled Soltys out as a leader. “I’m always suspicious of people who do that,” says Soltys. “I’d come into a meeting and he’d say something like, ‘The king himself!’ or ‘Our fearless leader, welcome!’ That sets off alarm bells for me.”

Showan often invited LIMITS organizers out for beers after meetings, and Soltys accepted on one occasion, to satisfy his own curiosity. “It was really hard to say no to him,” Soltys says, describing Showan as charismatic. “I didn’t really want to drink a beer, so I think I had a half pint. And then when I finished, he was like, ‘No no no, I insist, c’mon,’ and then when the waitress came he would say, ‘Two more,’ before I could even say anything.” Soltys says he did end up, after a few drinks, “sharing some stuff that was really dumb of me to share.” He shakes his head. “It’s a tactic, to always try to supply a lot of alcohol.” Soltys recalls a LIMITS campout in May 2009, when group members held workshops and stayed overnight at the Hanlon Creek site. “Bindo was there,” Soltys says. “No one else was drinking, but he had one or two two-fours of beer that he brought with him.”

After a few more months of organizing, and with no indication that the city was rethinking its plan, around sixty people, including some LIMITS members and supporters, walked onto the construction site at 6 am on July 27, 2009. Though Showan had attended every LIMITS meeting since January, he wasn’t aware the occupation was going to take place, Soltys says; the group didn’t officially endorse the action, and organizing was done quietly, on payphones and in person, in order to avoid cell phone and online police surveillance. By that point, organizers in Guelph were fairly certain that Showan was a cop. Zach O’Connor says that, from the beginning, Showan was “into shooting his mouth off.” Soltys says that Showan had a habit of talking about burning construction equipment, and that he made people uncomfortable with a constant assertion: “‘We’ll do anything to make sure this business park doesn’t happen.’”

When Showan showed up to the occupation, on the second or third day, Soltys says LIMITS activist Shabina Lafleur-Gangji told him the group needed him to “be an outside guy”—to give people rides in his big white van, which Josh Gilbert says was totally empty of personal effects, except for two Anti-Racist Action pins he’d gotten at an action that Gilbert organized. (Months earlier, Zach O’Connor had helped Showan move into a mostly empty apartment in Guelph. Even after he moved in, O’Connor says, all it really contained was a bed and a fridge.) When Showan returned to the occupation the following day, Soltys says that Lafleur-Gangji told him that the action was peaceful, and that he wasn’t welcome because he’d made people uncomfortable by talking about burning machinery. Though LIMITS activists didn’t confront Showan directly about their suspicions that he was a cop, Soltys says Showan must have known he was exposed after he was asked to leave the occupation a second time. He didn’t show up again.

Brenda Carey flew under the radar that summer. Though Soltys says she never stayed over at the occupation, she was often present. According to Soltys, she even went skinny dipping with a few people in the Speed River. “It was the last day of the occupation, and it felt like a success, because we’d stopped the construction work for now,” he says. “She was the last person to come in and take off her clothes, but she came in.”

Where Showan left off with activists in Guelph, he picked up in nearby Kitchener-Waterloo. Thirty-three-year-old Julian Ichim, who’s been an anti-poverty activist in Kitchener-Waterloo for over a decade, first met Showan in June 2009—before the HCBP occupation—at the Hamilton Anarchist Bookfair; the undercover officer stepped in when Ichim was arguing with younger activists about Che Guevara. Showan told Ichim that he was from Kenya, and they talked about the emergence of neoliberalism in his home country, as well as the Mau Mau uprising. The two struck up a friendship.

When activists from Guelph found out that Showan had popped up again, they tried to tell their counterparts in Kitchener-Waterloo that they thought he was a cop. But some people in Kitchener-Waterloo dismissed these warnings as racist and classist; Showan was in his mid-thirties, a person of colour and worked as a property manager. “When some people in Guelph were like, ‘We don’t like Khalid,’ we were like, ‘Why?’ And they said, ‘He’s older, he talks crazy,’” Ichim says. “Well, a lot of us are getting older, a lot of us talk crazy.”

Showan infiltrated the group Anti-War at Laurier, known by the acronym AW@L. (Several AW@L members ended up being named as part of the G20 Main Conspiracy Group.) According to Ichim and his former partner Kelly Pflug-Back, Showan continued offering to buy everyone beer, though people in Kitchener-Waterloo were more amenable to the idea than the Guelph activists had been. “The OPP must’ve paid for a couple thousand dollars worth of buying us beer and nachos,” activist Dan Kellar says in an April 2012 OpenFile video.

Initially, Pflug-Back says, Showan’s personality put her off. “Bindo would always find excuses to hug me,” she says. “He’d say, ‘Hey gorgeous,’ and then the whole time we were talking he’d be creepily looking at my chest.” Eventually, though, Pflug-Back says Showan won her over—because of the compassion he seemed to show by buying meals for her street-youth friends, and because of the time Showan spent with Ichim while the latter’s mother was dying of cancer. Ichim says that Showan became his friend by participating in political actions (like anti-Olympics demonstrations, one of which landed Showan’s photo in the New York Times), by caring about his health and the health of his friends, and by driving Ichim and his mother to the hospital when she was sick.

In early 2010, activists throughout Southern Ontario—including some of those under police surveillance in Guelph and Kitchener-Waterloo—started preparing for the G20 summit. People like Mandy Hiscocks, Alex Hundert and Leah Henderson—who work on indigenous sovereignty, anti-capitalism and queer rights, among other things—began attending meetings of a coalition called the Toronto Community Mobilization Network. The goal of the TCMN, as stated on its website, was to “come together and share the work that we do every other day of the year” and “transcend the systems that oppress” marginalized groups.

By now, the JIG infiltrators were firmly rooted, and Brenda Carey and Bindo Showan started attending TCMN meetings. Though Showan had been ousted from LIMITS, a year of talking about whether or not he was a cop hadn’t produced anything conclusive, and he was initially welcome at the TCMN. “‘Khalid’ offered to be my right hand,” Henderson says. “He was very actively trying to pursue a relationship with me. We would try to find the best goat curry in the city, and the best jerk barbeque sauce.”

Brenda Carey continued to elude suspicion. A month before the G20 summit, she moved into a punk house in Guelph where Mandy Hiscocks lived with a few other people. Another former tenant, who prefers to remain anonymous, says that the first thing Carey did upon moving in was paint her room hot pink and spray-paint a giant black anarchy symbol over her bed. Other than that, the former tenant says, she was a quiet roommate who brought beer home to share and “mostly just listened to other people talk.”

That summer, Carey helped Alex Hundert create a target list of corporations to protest during the G20 summit, advocating that it be “distributed as widely as possible.” The list was later used as evidence to charge Hundert and others with conspiracy to commit mischief. Carey also wore a wire to a final protest planning meeting on June 25, 2010. Hours later—just after 4:30 am on June 26, before the summit began—police burst into the apartment of Hundert and Henderson, arresting them, as well as Hiscocks, at gunpoint. Ichim was rounded up in front of a Tim Hortons later that day; Pflug-Back says that police yelled at her to stay back as they dragged Ichim into a van, where he says he “got his ass kicked.” Others who ended up bundled under the “G20 Main Conspiracy Group” moniker were also arrested that morning.

At a court appearance that day—just hours after the arrests—Crown attorney Vincent Paris said that the “G20 Main Conspiracy Group” advocated violence and aimed to hit “targets such as City Hall, Metro Hall, Goldman Sachs, the Bay and various consulates.” According to the Toronto Star, Paris said he was “overwhelmed by the volume of evidence collected” on the group.

During the protests, Black Bloc anarchists broke windows at some of the businesses that appeared on the target list Brenda Carey had helped create, including a CIBC at King and Bay. Alex Hundert insists that police didn’t need to infiltrate to figure out that property damage might happen. “All they had to do was read the call-out,” he told the Globe and Mail, referring to a May 2010 Southern Ontario Anarchist Resistance document. “This action will be militant and confrontational,” the call-out reads, “seeking to humiliate the security apparatus and make Toronto’s elites regret letting the dang G20 in here.”

Despite the infiltration and Carey’s role in writing the “target list”—and despite the wire Carey wore to the last planning meeting—police stood by on June 26 as protesters started fires and smashed windows. In a report released in June 2012, retired justice John Morden found that the property destruction didn’t receive police attention because officers were “focused on guarding the security fence around the site of the meeting.”

Though the police did nothing to stop the riots and fires that left parts of Toronto smouldering well into the night, they did repress lawful demonstrators the next day. On June 27, the final day of the summit, police notoriously kettled about three hundred protesters and bystanders at Queen and Spadina. About 1,100 people in total were rounded up at the G20 summit and taken to a temporary holding facility on Eastern Avenue; only forty were ever charged. In contrast, the Office of the Independent Police Review Director investigated 207 complaints against police stemming from the protests; it ordered disciplinary charges in 107 cases, and deemed 96 of those 107 to be “serious.” At least ten lawsuits and human-rights claims have been filed against Toronto police by people who variously allege that they were assaulted by officers, unlawfully arrested, shot with rubber bullets and held naked for hours in jail cells. One lawsuit, filed this summer after the OIPRD found the complaints to be “substantiated,” alleges that a group of women were profiled for having hairy legs. The suit claims that an officer arrested them as they emerged from a restaurant on Yonge Street; the officer allegedly called them “dykes” and told them to shave.

Eventually, Mandy Hiscocks, Alex Hundert, Leah Henderson, Peter Hopperton, Adam Lewis and Erik Lankin agreed to plead guilty to one count of counselling to commit mischief above $5,000; Hundert and Hiscocks also plead guilty to counselling to obstruct police. The other eleven members of the “Conspiracy Group” had their charges dropped, and no one ever ended up pleading guilty to, or being convicted of, conspiracy—which is defined, in Canada, as an agreement between two or more persons to commit a crime at some point in the future, whether or not any further actions are taken toward committing that crime.

In an opinion piece published on Rabble.ca, the defence attorney Peter Rosenthal says that, in his view, “prosecutors would have had real difficulties establishing that the talk at G20 activist meetings attended by undercover officers provided sufficient evidence for a verdict of conspiracy.” But Rosenthal asserts that counselling mischief is as simple as suggesting that someone commit an offence. “If I tell you to smash a Starbucks window,” Rosenthal says to me, “then I’m counselling mischief.” By pleading to the lesser charge of counselling, the activists avoided setting what they viewed as a “dangerous legal precedent”: the equation of political organizing with criminal conspiracy.

In November 2011, tape of the wire that Brenda Carey wore to the last meeting was leaked to the Toronto Star. One of the oft-repeated quotes comes from Monica Peters, who talks about people “blocing up” in order to “go off and do smashy smashy if they want to.” “That smashy smashy quote,” says Leah Henderson, “it’s a quote from The Simpsons. We may think we’re hilarious, but the government takes that kind of thing as having malicious intent.”

There was significant public outcry and a lot of media attention surrounding the burnt-out cop cars; Kelly Pflug-Back, for one, was eventually convicted of seven counts of mischief and one count of wearing a disguise for her role in the property destruction. But the level of vandalism that occurred during the summit is comparable to, for example, that of the 2011 hockey riots in Vancouver. “You really have to question why there was such a massive police response—why there was such a disproportionate police response to what really was property damage,” says Abby Deshman of the CCLA.

Deshman says that one of the CCLA’s main concerns is that overzealous policing will create a chill effect on dissent in Canada. This is an important point for all Canadians to consider, regardless of personal political convictions. Should environmental or anti-poverty groups be infiltrated and kept under surveillance simply because of their beliefs, on the shaky premise that they may encourage property destruction or civil disobedience in the future? Do we know enough about—and do we trust—how our governments and police agencies decide which groups to infiltrate?

Will Potter’s 2011 book Green is the New Red likens the current North American security focus on environmental and animal-rights groups to the anti-communist fear-mongering of the 1950s. Pointing out that environmentalists have not “flown planes into buildings, taken hostages, or sent Anthrax through the mail,” Potter questions why these groups—and not right-wing extremists who have “bombed the Oklahoma City federal building, murdered doctors, and admittedly created weapons of mass destruction”—have been named “the number one domestic terrorist threat” by the FBI. Here in Canada, Vic Toews’ terrorism targets parallel the ideological focus of the FBI. While he zeroes in on anarchists and environmentalists, he neglects to mention, for example, radical anti-abortion activists, who have shot doctors and firebombed clinics.

Many of the activists targeted by JIG have learned to be more cautious. Speaking after her release from prison, Henderson says that she plans to be more strategic about her involvement in activism, given Canada’s current security climate. She vows she’ll “consciously choose the things that put me at risk, and make sure I can stand behind them.” Alex Hundert, for his part, is “going to make some drastic changes on how I organize and who I organize with.”

Who are Brenda Carey and Bindo Showan, really, and why did they decide to participate in such a far-reaching infiltration campaign? I was unable to reach them for comment, and little is known about the pre-infiltration life of either officer. Carey once won a Can-Am silver in a 5-kilometre run; in 2006, her life partner, a fellow OPP officer, died in an on-duty car crash. Showan’s name pops up online even less. “I miss them as my friends,” Henderson says, “but they were never my friends.” Pflug-Back says that she saw Showan in person in Toronto, after it had been revealed that he was an undercover; she calls the experience “surreal.” Henderson saw Showan in court, also after the revelation, and she noticed “his body language, how he held himself, how he dressed was different.”

Josh Gilbert questions the utility of trying to understand their undercover personas at all. “We focus so much on their individual personalities,” he says. “But they’re not even people. Well, I mean, they are. I just don’t know if we’ll learn very much by interrogating the specifics of their identities ... There’s going to be a million undercover cops who replace them.”