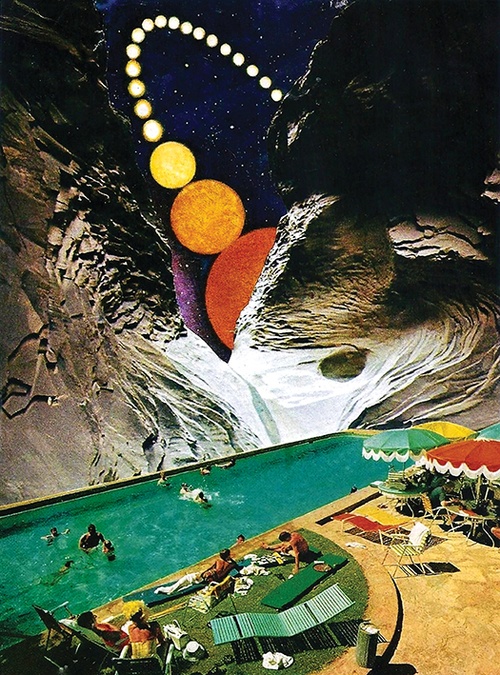

Illustration by Hugo Barros.

Illustration by Hugo Barros.

Agnosis

The first-place story from the 2013 Quebec Writing Competition.

“PLACE, TIME, SELF,” she said. “That’s how it all unravels. We think he recognizes people, the ones he sees every day. I don’t mean to suggest.”

“I was planning on coming on Friday or Saturday.”

“Friday would be better. It won’t make a difference to him. There’s something we need to discuss.”

There was always something to discuss. Care map, treatment plan, family wishes. Meetings that of course my father didn’t attend. He said little now. He had been lucid a year ago when I drove him here. As we got on the expressway he told me to go straight. “We could just keep driving,” he said. He wanted us to cross the bridge, as if he knew. A hundred kilometres farther on was the village where he’d grown up. Where the police had found him that last time.

I took the exit and turned left to the hospital. “We’ll be late for our appointment,” I told him. “It’s just for a check-up.” There were two nurses waiting to admit him. I jangled the car keys and said I’d wait for him outside, and maybe he understood just enough to know how it would play out. The next time I saw him he had lost the thread. He called me Moira, thinking I was his sister.

When I decided to move out I couldn’t tell my father. I told my mother instead. She didn’t ask why. She just started to make plans. Sheets and towels. Curtains. She never questioned my need to cut the cord, to be on my own, or alone; and years later— now—I wonder about that.

Dad announced that all of us would visit the new apartment. He was always looking for an excuse to drive. He liked the sense of freedom. Automobile, he said—have you ever thought what that means? Of course he took the long way, the tortuous way, and I was dreading his reaction when he saw where I had chosen to live. With him you never knew what to expect. But he said it was a good building, well constructed. He had done some of the work. Years ago, when he was a carpenter. You wouldn’t remember, you were very young. He told me he’d help with the move. He said he’d build some shelves for me.

There are movies of my early years, the two of us by the pool in our bathing suits in garish Super-8. He makes a face at the camera, flexing his muscles to show off his swimmer’s body.

He’d been something of an athlete in his youth, and when he left the farm for the city he’d done physical labour. Odd jobs in construction before he found permanent work at the railroad. He inspected the track and could walk for hours, a problem when he began to wander.

Before there were children they would take a walk after dinner, what my mother called their evening constitutional. They would stroll a mile or more to Gouin Boulevard to watch the television sets in the window of the appliance store. When there was a little more money they’d go to the neighbourhood tavern, where there was a black-and-white set just inside the Women and Escorts door. They’d nurse a beer all evening, watching the blurry images on screen: The Big Revue, Focus, Frigidaire Entertains.

What the director wanted to discuss was permission to videotape my father. He handed me a release form to sign. They wanted to ensure that everyone would be legally protected. Just a formality, he said.

“You’ve filmed other people?”

“We hire someone. I think she’s very good. It’s all digital so it’s quite affordable.” The video would be used to train the staff. “Your father gets frustrated, as you can imagine. It’s the illness. I’m sure it’s not who he was. People get like that in the kenotic phase. We need to show our people how to manage difficult patients.”

“Is there a problem at meal time? I remember the fuss he used to make at dinner, all the trouble my mother had cooking his food just right. He has a nervous stomach.”

“You wouldn’t know him now,” he said. “His appetite is fine. I think some of the nurses give him extra desserts as a treat. He seems to like that. Some days are better than others.”

“Is he in pain?”

“He can’t tell us. We give him medications just in case,” he said. “Morphine. Other things to control his anger. It’s all very routine.”

I watched an orderly cutting my father’s hair with large, blunt scissors. “I don’t understand. He seems fine now.”

“He doesn’t like to be touched,” the director said. “Henry’s the only one. Your father won’t let anyone else wash his hair.”

“Would Henry be in the video?”

“We’ll have to see,” he said. “Will you sign the form?”

AS A YOUNG MAN he had left everything behind: home, the pace of days, who he was known to be. He moved to the city, worked hard, married. Over the years the past was replaced by the future in a slow forgetting. When I was born I wasn’t baptized; religion, too, belonged to the past. For him it was another form of the old oppression. Being told who to be, what to think.

THE CAMERA WILL RECORD HIM as his clothing is removed. Skin pale in the video light, knotted ropes of muscle. Perhaps he holds his head because of some unvoiced pain. He may try to cover his nakedness: we clutch at our modesty even after we’ve lost everything else. The most enduring memories are of our humiliations.

There is a voice-over: a monotone of key teaching points as an orderly drizzles water over his head, and soaps his neck and face, and mouths reassuring words, and the patient moans.

IN HIS VILLAGE, the most celebrated event of the summer was a swimming race, perhaps a mile or more across the river and back again. He was too young to enter, but just old enough to want to prove himself. So he hitched a ride to the village, the wool bathing costume itching under his clothes. He took his place on shore with the other swimmers. No one asked his age. The river cold even this late in the summer as he lowered himself into the water. I try to replay how he had described it. The whistle, the pounding rhythm of arms and legs, the glare of water, and the waves breaking over his head.

He first told me about it when I was very young. I had slipped out of bed, the night too hot to sleep, and found him watching TV in the dark. “With the tides, the current was against you both ways,” he said. “When I was half-way across the river, I was so tired I thought I’d fall asleep.”

“I could do it, I could swim it,” I said, even though I hated cold water. “But was it hard?”

“It’s hardest at the beginning,” he said. “It’s hardest at the end.”