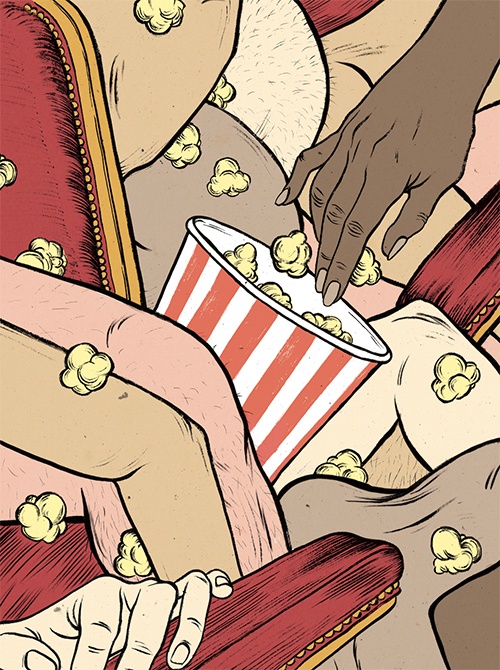

Illustration by Katie So.

Illustration by Katie So.

Coming Attractions

Alan Randolph Jones on Cinéma L’Amour, Canada’s last grand porn theatre.

THE FIRST THING I NOTICED upon entering the cinema was a sense of grandiosity that’s missing from contemporary multiplexes. A balcony hung over the seating, decorated with ornate trim that had remained intact for over a hundred years. The walls were decked in luxurious neo-classical mouldings, transporting audiences back to the glamorous golden age of Hollywood. The second thing I noticed was its state of disrepair. Paint peeled away from the walls, and though the lighting was dim, I could make out layers of accumulated grime in every nook and cranny. Unlike some of Montreal’s other still-standing movie palaces—the Imperial, the Rialto—this theatre had never been restored. Instead, it had accrued a century’s worth of wear and tear. Oh, and cum stains.

I spotted a scrunched-up tissue on the floor—contents unknown—which was soon kicked under a nearby seat. A funny smell hung in the air, which I placed to be semen, sweat and sanitizer. That could have been my imagination. But I definitely didn’t imagine the ghosts-of-ejaculates past covering the walls in the stairwell down to the washroom.

I was standing (not sitting) in Cinéma L’Amour, a notorious house of sin on St. Laurent Boulevard. With the exception of a few small peep show-style screening rooms sprinkled across the country, Cinéma L’Amour is the last grand porn theatre left standing in Canada. It’s also one of the oldest movie theatres in Montreal. Its combination of early modern architecture and late modern sleaze evokes a sense of urban decrepitude, of dive bars, flop-houses and other dirty establishments in what our grandmothers might have called “the wrong part of town.” As these less-savoury businesses were pushed out by high real estate prices and waves of gentrification, Cinéma L’Amour remained, a testament to the city’s smutty past.

DESPITE A LARGE YELLOW SIGN that can be seen from three blocks away, Cinéma L’Amour’s façade isn’t as garish or forthcoming as some of its competitors in the world of adult entertainment. Yes, there are neon lights proclaiming “Adultes XXX,” along with a few small posters promoting the current programming (Don’t Tell My Boyfriend I’m Cheating and So Young So Sexy POV #6). But the enclave, a hangover dating back to the theatre’s more palatable origins, is discreet enough that I’ve seen old ladies shelter themselves there from the rain while they wait for the bus. Even the name itself—L’Amour—sounds classy compared to something like Montreal’s Club Super Sexe strip club (which is itself on the site of an old movie theatre, the Colonial, built in 1912).

Over the past century, many of North America’s grand urban cinemas have been converted into retail storefronts, condos or even, in the case of Detroit’s Michigan Theater, parking lots. In Montreal, the Rialto in Mile End now serves as an event space, while the Corona in Little Burgundy was restored and turned into a music venue after thirty years of closed doors. The regal, 800-seat Imperial, which currently headquarters the Montreal World Film Festival, still serves its original purpose, but only programs films for a couple of weeks each year. Cinéma L’Amour is the only theatre in Montreal that has played films (porno- graphic or not) continuously for over a century.

It was in 1914 that the theatre—then called the Globe—opened, offering English and Yiddish movies as well as vaudeville to the Jewish working class immigrants who once populated the neighbourhoods around St. Laurent. In 1927, it changed its name to the Hollywood and eventually dedicated itself to double bills. After a brief spell as the D’Orsay, the theatre reopened on November 28, 1969, as the Pussycat, with a double bill of Lorna and Motorpsycho—five- and four-year-old sexploitation features from Russ Meyer, the so-called “King of Erotica.”

This move to showcasing sexploitation films was part of a wider trend across North America. In his book Montreal Movie Palaces, former Montreal Gazette film critic Dane Lanken portends that “[n]othing in the TV era saved more theatres than the public appetite for smut.” In the late 1960s and early ’70s in Montreal, the Français became the Eros, the Strand became the Pigalle, and the System became Ciné 539. In total, nine local cinemas began trafficking in material that was too scandalous for Odeon and Famous Players.

Hollywood itself was in crisis as North Americans began moving to the suburbs, where they started staying in and watching television. Theatre admissions in Canada dropped from a peak of 250 million annually in the mid-1950s to less than 90 million a decade later. Lanken, who witnessed the closure of several old movie theatres during these years, writes that, “a certain sparkle left the theatres with the advent of television ... The old palaces, nearly empty most of the time and given over to B-pictures and action dramas, began to look a little shabby.” As many downtown theatres shut their doors, the smaller neighbourhood cinemas that transitioned to sexploitation stayed open on the strength of tits and ass.

While Quebec arguably practiced the most draconian censorship in Canada (famously banning children under sixteen from movie theatres after a fire killed seventy-seven at the Laurier Palace Theatre in 1927), the 1960s marked a period of radical transformation for the province as the Quiet Revolution took hold and the new Liberal government began to secularize public institutions. “Before there were a lot of rules and practices that allowed people to intervene in the film, cut the film and censor it by scissors,” says Pierre Véronneau, a now-retired professor at Concordia University who has written about film censorship in Canada.

In 1967, Quebec’s newly formed Bureau de surveillance introduced age classifications for films to replace the former policy of censorship. While the bureau retained the power to refuse classification for a movie—essentially banning it—it was spearheaded by André Guérin, who Véronneau describes as “a true liberal-minded person, not willing to intervene and cut the films and censor them.” The bureau was remarkably lax compared to the Catholic-influenced censorship board that preceded it, but was still, ostensibly, against full-fledged pornography.

Nevertheless, a wave of sexploitation movies arrived over the next few years that toed the line between entertainment and porn. This relatively new and novel experience was usually tame enough to be sanctioned by local censors and to be advertised in daily newspapers such as le Devoir and the Montreal Gazette.

Quebec filmmakers even got in on the action with their own variation on the genre, called les films de fesses (literal translation: butt lms). Montreal-based Cinépix produced the first of these features, Valérie, which featured former Miss Quebec winner Danielle Ouimet as a woman who frees herself from a convent and travels to Montreal to become a go-go dancer. Valérie was a huge success and became a focal point for questions of national identity in the province’s media. The director, former Radio-Canada documentarian Denis Héroux, told the press that he wanted to “déshabiller la petite québécoise,” or undress the little Quebecker girl, with this film. That phrase (which reads as more sensual in French) stoked the public imagination and gave the film a political edge.

John Dunning, co-founder of Cinépix, wrote in his memoirs that, “Sure, critics could say we were kowtowing to the lowest common denominator of audience taste. But we were intent on succeeding.” More films de fesses followed, including L’initiation and Deux femmes en or, which courted controversies of their own in the French-language media.

Despite the hubbub, yesterday’s sexploitation films would barely be considered pornography today. “This was before you would see a lot of nudity in any kind of a mainstream film,” says Eric Schaefer, a professor from Emerson College who is currently writing a book on the history of the genre. “But that was what drew audiences to sexploitation films—the prospect of seeing these moving naked bodies on screen.” Scenes of topless women engaging in simulated intercourse may have seemed scandalous to some at the time, but viewed today, they’re about as raunchy as an episode of Entourage.

While the public often imagines the attendees of a porn theatre to be made up of old, lonely men, these early movies brought in audiences of curious onlookers and young people looking for a laugh. “During the ’60s, [the audiences] weren’t these kind of seedy, shambling bums,” says Schaefer. “These were pretty middle class and upper-middle class individuals.” After Valérie premiered in 1969, the Quebec tabloid Photo-Vedettes surveyed its audience, which seemed to consist mostly of unabashed young people.

But as the novelty of on-screen sex wore off and studios began incorporating elements from sexploitation into mainstream movies (just think of all the teen sex comedies from the 1980s), these early porn theatres had to change to survive. That meant doubling down on pornographic content and attracting the sort of trench-coat-wearing spectators that one now can’t help but think of when hearing the words “porn theatre.”

IN 1981, Ivan Koltai had a problem: the Pussycat wasn’t playing his movies. Koltai was in the business of distributing hardcore 35mm porn lms, and the owner of the Montreal theatre was playing maybe one in five of his offerings. “We needed [the Pussycat] to play our movies because that was the most pro table theatre,” explains Steve Koltai, Ivan’s son. The solution? Ivan bought the building and waited for the theatre’s lease to lapse. Then he opened Cinéma L’Amour in its place, matching the name of a theatre the family already owned in Hull (now Gatineau), Quebec, which has since closed.

At the time, the porn business was in the middle of a fundamental shift. The appeal of early erotic films had lost its lustre. Sexploitation had transitioned into softcore, which was less ambiguous about its content, offering more sex and less comedy. While hardcore pornography had a brief moment of notoriety in the United States with the blockbuster success of Deep Throat in 1972 (which allegedly grossed $600 million, though that number has been challenged), it would be another decade until theatres could screen similar movies in Canada without risking seizure by the local morality squad or even facing obscenity charges. But by 1982, with “freedom of expression” guaranteed by the newly adopted Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canadian theatre owners were emboldened to push those boundaries. Softcore gave way to hardcore, and the audience niche became even smaller.

Today, Cinéma L’Amour is essentially unchanged from 1982. There’s no other porn theatre in Canada that can boast the same. As with regular theatres, the arrival of home video and internet streaming have not been kind to public porn exhibitors. In Montreal, the Pigalle, the Midi-Minuit, the Eros and the Papineau all closed down. In 2013, both the Fox Cinema in Vancouver and the Metro Theatre in Toronto closed their doors for good, the former becoming a concert venue and the latter a rock climbing gym. That left Cinéma L’Amour as the sole holdout.

The Koltai family owns the Cinéma L’Amour building, meaning they aren’t impacted by the rising cost of rent in Montreal. But they still feel the pinch of a new online porn economy. Like any other movie theatre in the age of Netflix (and PornHub), Cinéma L’Amour is an anachronism, an institution built for a different time with different technological limitations. The business, Steve Koltai says, can no longer sustain itself. “We make money, but we make money based on the fact that we’re not paying rent,” he says. “If I look back ten years, I should have destroyed it and built condos ... I would have been better off.”

The one thing Cinéma L’Amour has going for it, Koltai explains, is its atmosphere. “It’s about social interaction,” he says. “I always compare our theatre to Cheers, the television show, you know, everyone has a friend.” The theatre caters largely to its regulars, mostly made up of older people and couples. “It’s a nice place to come, it’s a tranquil place, but it’s not about the porn,” Koltai says. “We create the ambience for them to get naughty.”

If one Googles “Cinéma L’Amour,” they will inevitably come across a number of stories con rming that people do, indeed, “get naughty.” Compared to the Cheers crowd, though, the ambience might seem a little too friendly to an uninitiated interloper. Most testimonials are written from the point of view of a curious outsider, visiting L’Amour on a lark and finding themselves in bizarre and sometimes frightening situations.

At Montreal culture blog Forget the Box, Jessica Klein documents witnessing a group blowjob session after an older woman and another man invited the theatre’s patrons into a roped-off couples section. “What perplexed us more were the seemingly bona fide lady noises coming from the middle of the circle,” she writes. “I guess we’ll never know whether it was a finger or something else causing her to squeak out sighs of satisfaction.” In the Vice article “I Took My Tinder Date to a Porn Theatre for Valentine’s Day,” Stephen Keefe recounts sitting in that same couple section with his date and being surrounded by lecherous older men who were expecting “a show.” As the men in the theatre began to congregate around them, Keefe writes, “We were the all-you-can-eat buffet for lonely perverts. I didn’t feel unsafe, but I de nitely did not want to get jizzed on by a stranger.”

These curious interlopers are often similar in background and age to the crowds drawn in during sexploitation’s heyday; self-aware, the theatre plays host for a variety of events that seek to capitalize on its notoriety. For a 2009 “40th Anniversary” party (referring to the opening of the Pussycat in 1969), the theatre played Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!, a 1965 Meyer sexploitation lm that transgressed its raunchy roots and became a bona fide cult classic. The theatre has even hosted events for local music festival Pop Montreal, including a live-band karaoke night for the theatre’s 100th anniversary in 2014—which is how I ended up inside Cinéma L’Amour in the first place.

When I ask Koltai if the theatre could find a second life by exploiting its still-magnificent interior and hosting community events, he responds in the negative. Between the long hours it takes to set up, and the costs associated with cleanup and insurance, event hosting is just not profitable—especially without a liquor license. “Unfortunately, we never got one and now [the city] won’t give it to us,” he says. Ideally, Koltai would like someone to invest in the theatre, restoring its interior and transforming it into a multi-purpose event space. Nevertheless, the theatre marches on, straddling the line between public and private and offering a heterotopia of sexual behaviour, one of the last of its kind.

AS FAR AS I COULD TELL, there was nothing sleazy going on at Cinéma L’Amour when I attended the Pop Montreal karaoke night. Instead, there was a live band playing House of Pain’s “Jump Around” while I drunkenly rapped along. An artsy video collage played on the century-old screen above me. I messaged my future girlfriend on Tinder (opening line: “Do you like the show Frasier?”), and apart from the fact that no one wanted to sit down on the possibly sticky seats, the inherent seediness of being inside a run-down porn theatre barely seemed to register once the party started.

Still, I couldn’t help but look up at the opulent horseshoe balcony, the exquisitely detailed mouldings and the sumptuous ornamentation and think to myself, I wonder what it’s like to jerk off in here?