Next Year in Krakow

Rebuilding Jewish culture in Poland is no easy task after its near-total erasure, and more than anything it takes imagination.

It’s morning in Krakow and I’m standing with several people at the edge of a park. A path cuts through rolling fields, sprawling and lush, edged with trees and wild grass. One in our group is a botanist, and he guides us through clusters of dandelion, chicory and horsetail. As he points to different leaves and flowers, he explains their various therapeutic uses. “I can give some to my Grandma,” one girl enthuses, as we come across a plant that’s apparently good for soothing arthritis. We’ve brought a stack of garbage bags, and each of us carries one, making them increasingly heavy as we fill them with uprooted plants and clumps of dirt.

The park is on the site of a former Nazi concentration camp called Plaszow. I’ve visited former Nazi camps before, including Auschwitz, which my paternal grandparents survived, and which I toured at sixteen with a group of Jewish teenagers. That day, I tried to reconcile the sight of tourist-filled, former gas chambers with the story of my Grandma’s eldest sister choosing to accompany her youngest sister there, after the girl was “selected.” I couldn’t, really. This outing feels discordant too, though in a somewhat different way.

We’re an unlikely group. The botanist drove in at dawn from Warsaw to meet a group of local Scouts, not Jewish, eight- and nine-year-olds with their teenaged leader and various parents in tow. Then there’s a Polish Jewish artist, an American Jewish academic, and me. After the walk, the Scouts will plant the yield in a newly dedicated public garden in the courtyard of a Krakow community centre, in a district once designated by the Nazis as a walled Jewish ghetto. Residents will tend the garden.

The medicinal plant tour is a sort of walking art exhibit, part of a new, weeklong art festival that examines contemporary Polish Jewish life. It was designed as “an experimental work of historical memory,” according to the program. It’s meant to get people—Jewish and non-Jewish Poles—thinking about how the site of horrific genocide is today a recreational space, the domain of exercisers and sunbathers. The American academic in our group, Jason Francisco, teaches at Emory University in Atlanta and has spent a decade visiting Poland to research and photograph Plaszow. More recently, he’s been taking pictures of the medicinal plants that grow here, fascinated by the idea that the physical earth of a place where genocide occurred could produce something curative. The festival brochure says the walk will provide a way to interact with the “forces of healing” Plaszow generates. Afterwards, its organizers hope, at least one group of non-Jewish Polish kids will see Plaszow as more than just a park. Before we started walking, Francisco gave us a rundown of Plaszow’s history. About ten thousand people were murdered in the camp, he told the group; they were shot, since there were no gas chambers.

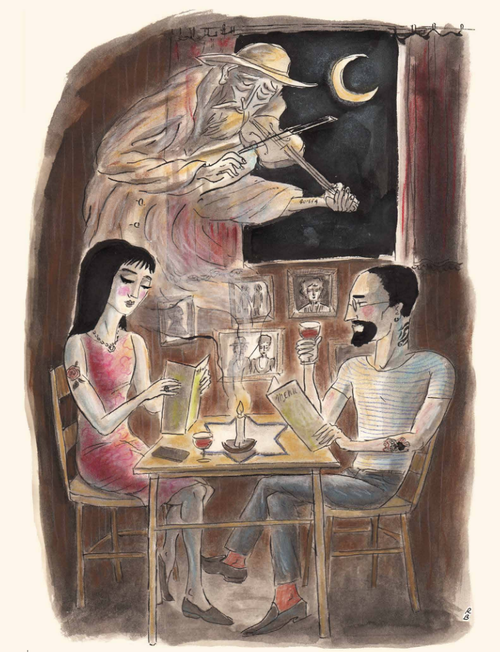

The festival’s organizers found their way here from disparate paths, and literally from around the world. Magda Rubenfeld Koralewska, in her thirties, was born in Krakow. Michael Rubenfeld is a Canadian whose family has Polish Jewish roots. Francisco is American, first meeting Magda at Krakow synagogue services. Now, they gather in the city’s historic Jewish quarter, Kazimierz, a neighbourhood that today is also indisputably the city’s hipster enclave. Its cobbled streets are dotted with vegetarian restaurants, galleries and revived Communist-era “milk bars”—a throwback to the canteen-like establishments that sold cheap meals to workers in the 1960s. Kazimierz also has a number of seemingly traditional restaurants advertising “Jewish,” and occasionally Kosher, food. It’s trendy.

Five years ago, Magda and Michael met in Montreal, at a conference. They talked about Poland; Michael had been planning to travel there to investigate his family’s history, for a play he was writing. They started dating, eventually splitting time between Canada and Poland. “We had to choose a country to base ourselves in,” says Michael. “So we decided to start with Poland.” In 2015, the couple married in a partially renovated synagogue in Kazimierz. It was the first Jewish wedding to take place in that synagogue since 1939.

For the average Jew of Ashkenazi background, Poland looms large in the historic imagination—if not as a direct ancestral birthplace, then as the faraway, practically mythic locale of the old-world Jewish shtetl. These were small market towns that existed before the Holocaust in Central and Eastern Europe, with predominantly Jewish, Yiddish-speaking populations (think Fiddler on the Roof). Unlike places like Germany or France, where Jews tended to be more assimilated into mainstream culture, Jews in Poland and some neighbouring Eastern European countries were generally more traditional, though many were urban-dwelling and secular. From Polish Jewish culture sprang movements like Hasidism, Zionism and Jewish socialism, as well as a lively Yiddish theatre and film scene and all kinds of food associated today with Jews, like bagels and gefilte fish.

Still, among Western Jews, feeling for Poland can hardly be described as warm. While the majority of Polish Jews were murdered by the Nazis, some Poles perpetrated their own pogroms against Jewish Holocaust survivors after World War II. Then came another dark period with the advent of communism, and in 1968, a campaign of state-sponsored anti-semitism drove most of the remaining Jews out of the country. North American Jews tend to see Poland as bleak, a literal and metaphorical graveyard, a place where Jews will never be welcome. When, as a teenager, I told my Polish-born, Holocaust-surviving grandparents about my upcoming trip to Poland, all shot me a version of the same disgusted look. “Why would you go there?” my late Bubbe snorted.

Within Poland, the memory of Jewish culture wasn’t so much bitter as it was buried. Four decades under communist rule erased Jewish history from Poland’s national consciousness. Considering the demographic history, that erasure is striking. In 1939, Jews constituted 10 percent of Poland’s total population, more than three million people. Jews now constitute less than 1 percent of the population; in the last national census, in 2011, fewer than eight thousand people identified themselves as Jewish. On paper, at certain times, it must have almost seemed as if Jews had never existed in Poland.

But since the fall of Communism in 1989, that memory has been slowly returning, as leaders of Polish Jewry and foreign Jewish press have heralded Poland’s “Jewish revival.” In those three decades, a handful of synagogues, two Jewish community centres and several Jewish schools have been established. And the community’s numbers are growing, too; more Poles are identifying as Jewish, and stories of people discovering a parent or grandparent’s concealed Jewishness have become relatively common.

To some extent, Polish society has encouraged this resurgence, founding its own festivals and celebrations of Jewish culture. Many of these events aren’t run by Jews, but by non-Jewish Poles. But the picture isn’t always rosy. A resurgence of white nationalism in recent years, complete with the government walking back some previous apologies and actions of conciliation regarding Polish persecution of Jews during and just after WWII, has raised questions from the international Jewish community about whether contemporary Poland is safe for Jews.

Jews living in Poland face a unique challenge. They must navigate thorny politics and contradictory attitudes towards them, while Jews abroad speculate about their fate. And Polish Jewry is by no means a united group, so its leaders work while battling internal community tensions, each group striving to assert its distinct vision of how best to foster new Jewish life, or pay tribute to the Polish Jewish life that preceded it. Most ambitious of all, they must graft a Jewish culture back onto a place where it was stripped away. Maybe it’s the complexity they face, in fact, that has made a new generation of Polish Jewish leaders deeply creative in their reimagining, and recreation, of Polish Jewish life.

Two years ago, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency ran an article that might, to readers outside Poland, have sounded strange. It described a non-Jewish Polish graffiti artist who had, for years, been scrawling “I miss you, Jew” on sites across Poland with important Jewish history. “I want to reclaim the word ‘Jew,’ snatch it from anti-semites,” he was quoted as having told a Polish newspaper. And last year, the JTA reported that a mock Jewish wedding had been performed in the village of Radzanów, featuring several dozen non-Jewish volunteers. The reenactment was meant to commemorate the hundreds of Jews who, before the Holocaust, made up half the village’s population. This kind of expression of philo-semitism is not uncommon, even in places that seem, on the surface, like they’ve lost any trace of Jewish culture.

Polish society’s ambivalence towards its Jewish citizens is less surprising to those Jews who have always remained there. And, contrary to what many Western Jews understand, there has always been some sort of Jewish community in Poland, however small. Konstanty Gebert is a prominent Polish journalist who writes for the liberal newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza. Born in Warsaw, his father was a top Communist Party official whose family were Polish peasants. On his mother’s side, Gebert is Jewish. His maternal relatives, most of whom were killed in the Warsaw ghetto, were assimilated Jews belonging to the Polish intelligentsia. Gebert has always known he was Jewish, but says he’d considered it an “irrelevant biographical detail” until 1968. That year, the Communist government unleashed a state-organized anti-semitic campaign, which Gebert says “forced me to delve into my heritage.”

Gebert knows—has himself been a part of—the resourcefulness it has taken to sustain even the most meagre Jewish culture in Poland. The Communist regime supported the vision that post-WWII Poland was monoethnic and Christian, he says. Several Jewish cultural institutions, like the Jewish Historical Institute and the Polish State Yiddish Theatre, continued to be active, but they were tightly controlled by the regime, and, Gebert says, were “morally discredited by their enforced, slavish obedience to the party line, including its anti-Zionist aspect.”

In 1968, the government scapegoated Jews, removed them from jobs in public service and pressured them to leave Poland. Many did leave, but Gebert went the opposite direction—he became a vocal supporter, he says, “of Jewish life.” In 1979, he helped found the “Jewish Flying University,” part of the so-called Flying University movement, an underground network of people who got together to study topics forbidden by the Polish communist government, including the Polish Jewish question.

He was one of a number of young Jewish descendants, many from assimilated families, who opposed Communism in the late seventies. These “new Jews,” as some called them at the time, began working to find and restore the remaining traces of Jewish presence in Poland, such as synagogues and cemeteries. Bolstered by some Jewish support from abroad, they opened several schools and summer camps and ran cultural and educational Jewish programs, mainly for a Polish audience. They also launched periodicals, including Gebert, who, in the late 1990s, founded a Polish-language journal called Midrasz that covers Polish, Jewish and Polish-Jewish art, culture and history.

The taboo around Jewishness has lifted gradually through the years in wider Polish society. The Jewish Culture Festival, a ten-day program of workshops, lectures, and concerts, was created in 1988 by non-Jewish Poles to honour Jewish contributions to Polish culture. It became not only a tourist draw but a mainstay of Krakow’s cultural scene; last year, almost 70 percent of attendees were non-Jewish Poles, according to the festival director. About fifty smaller festivals are held each year to celebrate Jewish culture, including in places outside Poland’s large cities that are today staunchly Catholic—there’s been a Jewish festival in Zelów, for example, a town with some seven thousand inhabitants. Before World War II, however, 3,500 Jews also lived there.

One sea change clearly began to emerge from this cultural thawing. When Magda was a child, growing up in a Catholic household in Warsaw, she gravitated to Jewish art and culture, though she wasn’t fully conscious of it then, she says. Her favourite poet—Julian Tuwim, whose poetry she remembers reciting at school events—and favourite jazz musician, Mikolaj Trzaska, were both Jewish, she later discovered. Her grandfather used to play a Klezmer record at Christmas. It had been a gift from a Jewish couple whose lives he, a doctor, had saved after WWII, when they’d been in a car accident. In high school, Magda’s first boyfriend had Jewish roots, and she found that many of her subsequent close friends and boyfriends were also Jewish. She began traveling abroad to learn English and Spanish, and she found herself drawn again and again to Jewish people and culture.

Now thirty-six, Magda is a graphic designer by profession. She has jet-black, partly undershaven hair, and speaks with quiet, razor-sharp lucidity. She’s also one of Poland’s Jewish leaders, after officially converting to Judaism fifteen years ago. She quickly became involved in rebuilding the fragile community, and particularly in developing outlets for those wanting to explore their Jewishness who might not be comfortable with the Orthodox route.

Magda knew a Jewish community had always existed in Poland, but as recently as ten years ago, it was focused on building at the most basic level, like creating synagogues and acquiring Polish-language prayer books. She joined the board of a Reform synagogue in Warsaw and then co-founded her own Reform community, called Beit Krakow, which grew close ties to the local theatre scene. In addition to co-founding FestivALT, the summertime art festival that included the botany walk, Magda also curates an exhibition of nineteenth-century Jewish art and helps organize a music festival that aims to reinvigorate the Jewish music scene in Poland. When I called her in early October, she barely had time to speak, as she was also running for a seat in her district council in Warsaw.

As Jewish history has made its way back to Polish consciousness, thousands of Poles have discovered their own Jewish roots, often during a grandparent’s deathbed confession—somewhere around twenty thousand people, by most estimates. Conversions to Judaism have also been part and parcel of this period, including some by people who, like Magda, converted despite not having Jewish lineage.

Rabbi Michael Schudrich is the chief rabbi of Poland and the leader of Warsaw’s Noz˙yk Synagogue. Originally from New York, Schudrich first travelled to Poland in 1973 on a Jewish youth trip, frequently returning and even attending the second-ever meeting of the Flying Jewish University. He moved to the country permanently in 1990, quickly founding introductory classes on Judaism that have continued ever since. Several hundred Poles have attended them, Schudrich says: Jews whose religion was covert during Communism, Poles with Jewish roots looking to formally convert, and non-Jewish Poles also interested in converting.

In the nineties, Schudrich says, those rebuilding Jewish community consciously tried to avoid reproducing pre-Holocaust Jewish life, or mimicking the conventions of American Jewish life; in practice, this has often translated to abandoning customary social divisions. For example, the leaders of Poland’s Jewish community tend to be in their thirties or forties, a generation younger than the typical leaders of North American Jewry. And while Schudrich’s synagogue is affiliated with Orthodox Judaism, he is reluctant to claim the title of Orthodox rabbi, adamant that in Poland, he is a rabbi “for all Jews.” In the West, by contrast, one’s position on the denominational spectrum, and especially a rabbi’s, carries serious weight. Schudrich says he wants to “empower every Pole discovering Jewish roots to find their way of expressing their yiddishkeit”—an Old World way of saying “Jewishness.”

The enthusiasm of both Jews and non-Jews has been crucial to the cultural groundswell, says Jonathan Ornstein, the executive director of Krakow’s Jewish Community Centre (JCC). Originally from New York, Ornstein moved to Poland about seventeen years ago to be with a non-Jewish Polish woman he’d met on a kibbutz in Israel. The relationship didn’t work out, but Ornstein found work teaching Hebrew in the Jewish Studies department at Krakow’s Jagiellonian University, fell in love with Poland, and stayed. He was amazed, he says, to see the interest in Jewish culture among non-Jewish Polish students, many of who were doing graduate work in Jewish Studies. That has allowed the so-called Jewish revival to occur, and particularly for Poles to discover and publicly pursue their own Jewish heritage. “The two go together,” he says. “If young people were finding out they had Jewish roots but the environment wasn’t welcoming, they wouldn’t do it.”

Then, ten years ago, the JCC opened and he became its director. Ornstein and his colleagues began to reimagine the JCC institution in Poland, and “to be as inventive as we can,” he says. “We had no idea how we wanted it to be.” They decided to make the building’s interior bright and colourful, as welcoming as possible, and spelled out a message of welcome on its exterior—on a fence facing the street, a vinyl sign reads, in English, “Stop by and say hi.” In fact, the centre relies often on non-Jews, including fifty-five non-Jewish volunteers who help with duties like reception or at communal Sabbath dinners. Ornstein met his wife at the JCC—a Polish woman, one of the many Poles who discovered their Jewish roots in adulthood.

The JCC is mainly funded by donations from Jews in North America, plus a small amount from the Polish government. To be sure, Poland’s history and politics still trouble Jews overseas. But when Ornstein travels abroad to solicit funds, he tries to focus on that cheerful message. “We have an opportunity to bring lost Jews back into the family,” he says. “It’s a pretty good situation here… non-Jews working with Jews [to rebuild Jewish life], that’s something the world needs to know about.”

For Magda, the progression from Catholicism to Judaism wasn’t particularly jarring. She hadn’t been a practicing Catholic for years. But also, “Poland is a country where you grow up with a lot of traces of Jewish culture and history, even if you’re not completely aware of them,” she says. “You can almost say that one is not complete without the other.” I ask Magda what it is about Judaism she finds so enticing. “The grey areas,” she says. “The nuance. The contradictory opinions that I think Judaism fosters…this was something I found very natural.” Starting FestivALT was meant to create a platform for this kind of criticism. Its organizers “have very strong ideas about things,” Magda says. “We don’t, I hope, impose those on our audiences… But we don’t leave things as they are, as though they’re normal.”

This June, in Krakow, Magda’s husband, Michael, sported a voluminous beard, his hair a mass of curls. His look was hipster-shtetl mashup: dark trousers, suspenders over a white collared shirt, a cap, sometimes a vest. Pictures of him in this getup appear all over Kazimierz, as it’s the central image on the posters for the festival Magda and Michael run, FestivALT. “I get into the shtetl look here,” he says, sitting down in a Kazimierz café for an interview. But the outfit was also a very specific costume.

Go to any traditional Polish market or souvenir shop, and among the trinkets you’ll find figurines and pictures of a stereotypical-looking Jew in Hasidic get-up, quite literally counting his money. They are called “Lucky Jews” and have been bought by Christian Poles as a sort of good-luck charm, to bring wealth. When he first encountered this, Michael says, “it seemed completely bonkers.” For any Jew, “you understand that a stereotype of a Jew holding a coin is deeply problematic.” Then, two years ago, the idea came to him to transform himself into a real live Lucky Jew. He built a market stall with an opening for him to stick his head (or anyone else playing the Lucky Jew character—several of Michael’s friends have also done it). Michael also prints photographs of himself as the Lucky Jew on mugs, puzzles and magnets and sells them at markets. He sells his own image for luck.

Reactions among Poles have been varied. When he does the act in a market mostly attended by Polish people who recognize the Lucky Jew concept, some “think it’s hilarious,” Michael says. “And having people think it’s funny is great. It means they get it.” Then there are those who don’t seem to get the joke but still buy his iteration of lucky Jew trinkets. “You could say that it’s better they’re putting a real Jew on their wall,” Michael said. “Or you could say, if someone puts an image of me like this on their wall, at a certain point someone will ask what it is. They’ll have to be in conversation about it.”

Born in Winnipeg and raised there and in Toronto, Michael went to Hebrew school, where he says he “was taught to love Israel, was taught only about Israel.” And, of course, the Holocaust. “It’s almost like contemporary Jewish history starts with the Holocaust,” he says. “But that’s not true.” Now thirty-nine, Michael first visited Poland in 2013, with his mother, as he began to work on a play about family history and intergenerational trauma. For the next few years, he returned to Poland a number of times, primarily to visit Magda, but also to further develop the play. He called it We Keep Coming Back and premiered it in Krakow at the 2016 Jewish Culture Festival, later performing it across Poland and Canada.

But the trips to Poland also left him disconcerted, he says; he felt that, throughout his life, he’d been missing a core piece of his identity, one he’d never considered relevant. Poland felt to him like the only place where that identity could be nourished. “There’s this incredible, thrilling world of Jewishness in Poland,” he says. “The version of Judaism that [Ashkenazi Jews] practice, or don’t practice—that came from here.” Though he has maintained his career in the Canadian theatre world—from 2008 to 2016, he was artistic producer of Toronto’s SummerWorks Performance Festival—he began dividing his time between Krakow and Toronto.

Several years ago, Michael and Magda were sitting around the dinner table in their Krakow apartment with Francisco and another friend—Maia Ipp, a Los Angeles writer who Michael had met after a production of his play in Krakow. All had come to the conclusion, Magda says, that Poland’s Jewish community could use an alternative to Krakow’s prominent Jewish Culture Festival, the one founded in 1988. They appreciated the role the festival has played, they agreed, and weren’t seeking to replace it. But they also saw an opening, a need for greater introspection among Polish Jews. “The main festival can’t do this,” Magda says, “because it’s about bringing Jewish culture to the masses, rather than looking inwards. We wanted to look inwards.”

For Michael, part of the problem with the Jewish Culture Festival was that its focus has shifted, over the years, from exploring the contemporary Jewish question to being quite Israel-centric. This year’s theme was Zion. Michael said this immediately complicates things for “anybody Jewish who’s even remotely left-wing… People are coming to engage with questions of Judaism in Poland, and they’re immediately met with a Zionist perspective on Israel.” (Michael himself, for political reasons, won’t currently travel to Israel.)

It also made him uneasy that that focus was picked by non-Jews. “While I think some of the most important work being done on Jewish memory in Poland is happening by non-Jewish people,” he told me, “I feel like this is them thrusting themselves into a most essential political Jewish conversation.” (Robert Gadek, deputy director of the Jewish Culture Festival—he is not Jewish—told me his team’s intention was to recall pre-modern connotations of Zion, “the mythological longing for homeland” rather than contemporary Israeli politics, especially this year, to help mark the hundredth anniversary of Polish independence.)

They would deliberately run the alternative festival, FestivALT, concurrent to the existing one, the friends decided. It would use art, all kinds of art, to explore new ideas, including publicly enacting some of Poland’s ugly or absurd Jewish stereotypes as a way to rejig peoples’ perceptions. But the FestivALT founders didn’t want to shy away from turning criticism inward, not just towards historical persecutions—to look at how things get done in the local Jewish community, and factors that may be thwarting its growth.

Magda and Michael maintain that Jewish communal property in Krakow has been mismanaged by what’s known among local Jews as the “official” Jewish community. They’re referring to their city’s branch of the Union of Jewish Communities in Poland, or, as it’s nicknamed in Polish, “the Gmina.” This world of officialdom constitutes one kind of effort to preserve Jewish life in Poland, but not everyone agrees with how it has gone about it.

The Gmina is an association first formed by Polish Jews in the late 1940s to try to sustain Jewish religious presence after the Holocaust. It operates synagogues and prayer houses across Poland and has about seven hundred members; it’s open to any Polish citizen with at least one Jewish grandparent. In 1997, Polish parliament also gave it authority to reclaim all religious communal property belonging to the Jewish community before World War II. As a result, the Gmina owns nearly every known Jewish cemetery, synagogue, school and hospital, as well as and other Jewish landmarks in Poland, and has the power to redevelop, sell or lease them as it sees fit. In the Krakow wing of the organization, “there are a handful of decision-makers who call all the shots,” Magda says. There have been many mistakes, she says, “in terms of how heritage is being wasted away.” Anna Chipczyńska, an official in Warsaw representing that city’s branch of the Gmina, says the organization’s decisions about various sites are regulated by many general laws and Jewish religious rules.

Some people’s frustrations are bigger. There was an international fundraising drive in the early nineties, when the Gmina was founded, says Rabbi Haim Dov Beliak, a California-based rabbi who has been visiting Poland for years. Jews from all over the world were encouraged to give money to Jewish causes in Poland, with much of it ending up with the Gmina, Beliak says. But Jews abroad also assumed that Poland’s remaining Jews would leave Poland, whether for Israel, North America, England or elsewhere, so they didn’t plan how the money could be used to rebuild Jewish society there. “Normally a community gets money, and the first job is to say, ‘What are the priorities here?’” says Beliak. “‘‘Should we develop a nursery school?’ There was nothing of that kind.”

This summer, I headed into a Kazimierz bar with a group of around twenty-five people, led by Magda. It was another FestivALT event, a combination of protest and exhibit that the organizers dubbed an “artist intervention.” The FestivALT group had chosen to protest in a certain building, a nineteenth-century prayer house and yeshiva designed by a prominent Polish-Jewish architect. In 2012, Beit Krakow, Magda’s progressive Jewish community in Krakow, submitted a proposal to obtain the building and convert it to a centre for Jewish art, creative study and community gathering—they envisioned a theatre, exhibition hall and cafe there. They were denied with little explanation, they say, and the Gmina subsequently leased the building first to a nightclub, then to the current business. The congregation that once prayed here was called Chevra Thilim, meaning “Society of Psalms”—so the bar used that as a namesake, calling itself “Chevre.” In order to create a secondary entrance, the owners of Chevre dismantled the alcove that had once housed the synagogue’s ark, a sacred Jewish item used to hold the Torah.

We gathered at a long table inside the bar, asked by the organizers not to buy anything if we could help it, so as not to support the business. Magda climbed onto a chair so everyone could hear her and outlined the building’s history. On the wall behind her was a peeling fresco, what remains of the synagogue’s original artwork, the faded turquoise and Hebrew script coming off in strips.

Still, maybe the very existence of these internal community tensions is a sign of progress. Magda argues that the existence of FestivALT is testament to the fact Polish Jewry has moved past survival mode. “Being able to do FestivALT is a luxury,” she says, “something we can afford to do because the community is okay.”

Memories of Jewish culture weren’t the only thing suppressed during Communism. Poles were also fed propaganda that their own people “were not responsible” for the war’s atrocities, says Peter Jassem, a native Pole who lives in Toronto and for years chaired a nonprofit meant to pay attribute to the shared heritage of Poles and Jews. Many Poles still believe that any crimes against Jews in their country in World War II were committed either by Nazis or by a fringe element of Polish society, “hence, not worth mentioning.”

This has made the discussion of Poland’s Holocaust history fraught. And these tensions seem to have worsened of late, giving rise to new worries about nationalistic populism and racism.

Many Poles object to any use of the phrase “Polish death camp,” saying its normalization will cause younger generations to believe Poland, not Nazi Germany, was responsible for the Holocaust. In 2012, then-U.S. president Barack Obama was rebuked by Poland’s Foreign Minister for referring to “Polish death camps” in his tribute to a Polish war hero. In 2015, Poland elected the right-wing, populist Law and Justice party. During the campaign, current president Andrzej Duda criticized the then-president for issuing a public apology for a 1941 massacre of Jews by Polish farmers in one village. In 2017, the government downplayed neo-Nazi sentiments expressed during a large white supremacist rally. On November 11 of this year, a nationalist march in Warsaw drew more than 200,000 people, some carrying the banners of far-right parties in Poland and Italy.

Most controversially, in early 2018, the government passed a law that penalizes public assertion of Poland’s complicity in the Holocaust. In the law’s first iteration, references to “Polish death camps” and suggestion of Polish complicity in Nazi crimes would have been punishable by up to three years in prison. The law spurred backlash around the world, and not only among various Jewish communities—the U.S. State Department put out a statement condemning it for undermining free speech. (Many Poles opposed it as well, Jassem says.) Four months later, the Polish parliament caved to pressure and amended the law to make mentioning certain parts of Holocaust history a civil offence rather than a criminal one.

There is certainly some history of Polish solidarity, including a citizens’ group that risked penalty of death to help thousands of Polish Jews. Yad Vasham has recorded 6,532 individual Poles who rescued Jews during the Holocaust—more than in any other country. But to deny all incidences of Polish complicity goes against a swathe of evidence as well. One Polish study found that found two out of three Polish Jews who tried to survive the Holocaust by hiding in the countryside died, often due to Polish participation. Research by the Holocaust Memorial Museum shows that individual Poles often helped Nazis identify and hunt down Jews in hiding, and that many actively plundered Jewish property.

Still, despite the Holocaust-denying legislation, Polish Jewish leaders say they don’t necessarily consider their government anti-semitic. The government may tolerate anti-Semites when it’s convenient, Gebert says, not wanting to alienate this component of its base, but it also vies for good relations with Israel. Still, the law was worrisome enough that after it passed, the Jewish Culture Festival’s organizers weren’t sure if their funding from international Jewish organizations would be affected. Shortly after, a thousand prominent Poles and Israelis signed an appeal sent to Polish politicians. “No law…will change the facts of the past,” it reads. “Do not divide us. Again.” The leaders of the Jewish festival also sent their own letter, and afterwards, they braced for a barrage of public criticism, Gadek told me. It never came. Generally, though “we are trying to avoid politics… as much as possible,” he said.

Krakow’s historic Jewish quarter of Kazimierz feels a bit like a village, at least in late June, during the two concurrent Jewish festivals. Festival-goers frequent a cluster of trendy, Jewish-style cafes— borscht, hummus, bagel-like pastries and hipster vegan fare. Live Klezmer floods the neighbourhood’s bars and public squares. On a busy street near the Vistula River, Magda and Michael’s walkup is full of people, a pivotal venue for their own festival. It’s open and high-ceilinged, lined with Jewish artifacts. The living room is alternately a makeshift gallery displaying photography and a stage where performance art is performed and theatre workshopped.

One evening, the apartment is transformed into the gathering of a mock witches’ coven. The event is titled “Women on Women,” and the program explains that “wherever and whenever women gather together, it arouses suspicion, titillation and trouble. What exactly are those women up to…?” The plan is to “cook, conjure spells and scheme,” and the living room and kitchen areas turn fragrant and smoky, with guests put to work chopping fruit for a “brew,” which in this case resembles a boozy punch. Several performances follow. Witches have always been found in part of Jewish culture, says one of the women performing. She references a quote attributed to a famous Jewish sage, albeit a seemingly paternalistic one: “The more wives, the more witchcraft.”

At the time, Magda was about four months pregnant. On another night, audience members packed into the apartment to workshop a new, autobiographical play Michael is co-writing about being Jewish in today’s Poland. The dialogue keeps circling back to a theme: his reservations about raising a child here, with nationalist politics threatening to stoke not just anti-semitism but also Islamophobia, homophobia and misogyny.

Several months later, I ask him how he’s feeling. It’s complicated, he says. “Polish society is hugely Polish-Catholic, and it mostly consists of a system of values I find extremely narrow,” he writes in an email. “[It’s] becoming narrower because of the influence of the Church, and also the current government is teetering on the edge of totalitarianism.” It makes the idea of raising a child there tough to stomach. “At the same time,” he writes, “there is something very meaningful about having a child in the country my grandparents and great-grandparents were born in.”

I recall an earlier conversation we had, back in Kazimierz. I had asked why he and his co-organizers have chosen art as their medium for scrutinizing Jewish life in Poland. “Art asks people to engage emotionally, as well as intellectually,” he answered. He’s interested in acts of full transformation, he says. Art lets you attain that. In a place where historic memory is so elusive, rebuilding a lost culture will never be simple. But beyond imagining what can never be recovered, this Jewish art imagines what could be; in this way it is, like the plants that grow in a former death camp, very much alive.