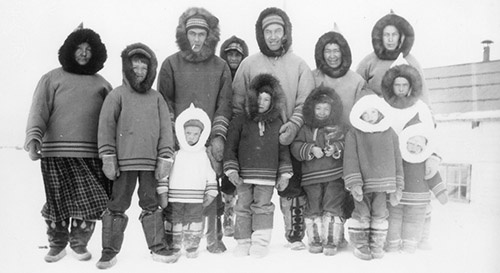

Sheila Watt-Cloutier with her family in Kuujjuaq.

Sheila Watt-Cloutier with her family in Kuujjuaq.

Tamanna Anigutilarmijuq

Canadians are scared of losing the life they know, Inuit leader Sheila Watt-Cloutier writes. Maybe looking north will help.

I remember, as a child, watching my brothers Charlie and Elijah as they got ready for family hunting trips. They first cut damp peat moss from the soil in squares and brought it home, where they checked it for any small stones. My brothers tended to do this the modern way—with their hands—but traditionally hunters would have put chunks of peat moss into their mouths to find and remove the stones.

This was part of preparing the qamutiik, the dogsled. Once the peat moss had been cleaned, they shaped it around the bottom of the sled runners. Then they cautiously dripped small amounts of warm water from their mouths unto the runners once they applied the peat moss. They did all this outside in the freezing cold, the steam rising up in little clouds as they worked. While the water was forming a layer of ice on the moss, my brothers polished it with a small piece of wet caribou fur until everything was frozen hard. They repeated the process until several layers of ice had built up on the runners, sometimes smoothing the ice further with a plane. Once the peat had a thick, hard surface of ice, the runners would glide easily on the ice and snow.

Charlie and Elijah worked with absolute focus and attention. It was almost mesmerizing watching them labour in the same meticulous way that Inuit had worked for generations. I learned from watching my brothers that safety was everything. You had to be extremely careful and precise, both for your own welfare and for that of your family, who relied upon your ability to lead the dog teams out onto what most people would consider a harsh, difficult and rough terrain.

The Arctic may seem cold and dark to those who don’t know it well. But I knew better. As the youngest child of four on our family hunting and ice-fishing trips, I would be snuggled into warm blankets and fur in a box tied safely on top of the qamutiik. I would view the vast expanses of Arctic sky and feel the crunching of the snow and the ice below me as our dogs, led by Charlie and Elijah, carried us safely across the frozen land. I remember just as vividly the Arctic summer scenes that slipped by as I sat in our canoe.

When I was born in 1953, my small family lived in Old Fort Chimo, a tiny community in northern Quebec, in the region that would eventually become known as Nunavik. Fort Chimo was a mispronunciation of saimuuq, which means “handshake.” In Inuktitut, the place had always been—and is now again—called Kuujjuaq, meaning “great river.”

Kuujjuaq sits just below the treeline, and the rolling, hilly terrain is dotted with tamarack and black spruce trees. During the short summer months, cloudberries, blueberries, arctic cranberries and black crowberries grow among the green leaves and tundra. Fluffy white cottongrass and deep-pink fireweed wave in the breeze, and bluebells, green mosses and grey lichens spread out across the land. But the idyllic moments of my childhood seem very far away these days.

The news in southern Canada is now full of images of floods, wildfires, droughts, intense tornadoes and hurricanes. People are losing their homes, losing their livelihoods, all that they have worked for throughout their lifetimes. Many are calling this a “state of emergency.”

I understand this fear of havoc and destruction. For decades now, Inuit have been living in a state of emergency of some kind or another every single day. In a sense, Inuit of my generation have lived in both the ice age and the space age. The modern world arrived slowly in some places in the world, and quickly in others. But in the Arctic, it arrived in a single generation. Tumultuous change, as well as cultural oppression, began to diminish our identity, our sense of self-worth.

We suppressed many traumas from the colonial past, especially the mass killing of our sled dogs by government decree, a sudden loss of an immemorial way of life. Addictions and violence took root, the symptoms of unchecked traumas endured. More than that, we were poisoned from afar by toxins that ended up in our food chain and affected by UV radiation as the ozone layer at the top of the world was depleted. Then came bigger climatic changes. We had thought our ice was as permanent as the rivers and mountains of the south.

In other words, we’ve already been through the sort of precariousness southerners are now dealing with. So let me share some of what I’ve learned.

When I returned to Kuujjuaq as an adult, after years away, I worked in the school system. That made it impossible for me to miss how the wounding of the previous generation was having a dire impact on the next generation. Many children were struggling to attend school because of lack of sleep or nourishment. Some were now witnessing violence in their homes. The teenage light-heartedness that I remembered from my younger years, the sense of optimism, was missing. When a young woman first took her life in Kuujjuaq, it sent shock waves and disbelief through the town. Over time, tragically, suicide became something our communities were experiencing repeatedly.

So much was beginning to be disorienting. The very wind patterns and cloud formations altered, so elders could no longer tell by looking up whether a storm was rolling in. Reports of skin cancer, cataracts and rashes were on the rise. For the first time in our lives, many of us Inuit had to wear sunscreen and sunglasses when outdoors.

Most shockingly, like all my fellow Inuit, I have seen what seemed permanent begin to melt away. In the past, we could glance at ice and accurately gauge its depth and its stability. But now, what looked like solid ice might actually be thin or unstable. For a people who spend much of their life moving across snow and ice, this was profoundly troubling—and dangerous.

All my years growing up in Kuujjuaq, I don’t recall many stories of hunters having accidents with breaking ice. When I moved to Iqaluit, I heard of such accidents almost every day. My neighbour, Simon Nattaq, had fallen through the ice on a hunting trip soon after I moved to Nunavut. He pulled himself out of the water and, in soaking wet clothes, dug himself into a snowdrift for insulation. He spent two days that way before he was found. Both his legs were already frozen, so they had to be amputated. I witnessed his healing from across the street as he slowly but surely learned to get about on his prosthetic legs.

As the years passed, I would see this seasoned hunter getting back on his snowmobile or his four-wheeler, going off to the land and sea to hunt. Simon’s ability to overcome his great challenge and remain a provider for his family was an inspiring example of the strength and resilience of an Inuk hunter.

There’s a common saying among us Inuit: Tamanna Anigutilarmijuq, which means “this too shall pass.” I’ve taken solace in this thought. And in the belief that these moments, when life seems to be breaking down, often signal that we are on the edge of a breakthrough in our lives.

When I give talks around the world, I am never prescriptive as to what can work for others. But Inuit often say, go out on the land. We have found that nature is the natural teacher for life. When one is waiting for the snow to fall, the winds to die, the animals to surface, nature is teaching you patience. Being out on the land not only teaches you about nature, the environment and how the planet is changing, but it also teaches you about yourself—how you can develop perseverance, courage, persistence. How to be bold under pressure, how to be focused, how to become a natural conservationist and, ultimately, how to develop sound judgement and wisdom.

Older generations have carried these skills with them as they navigate our new, precarious, rapidly changing conditions. But I worry, because as we lose ice, we lose the ability to teach our children the wisdom that goes with it. Our youth need these character-building skills more than ever.

We are finding in our own research, for example, that suicide is a very impulsive act. If you have learned that impulsivity on the land puts you and your family at risk—if that ability to be patient has been ingrained in the core of your being—then when stressors come your way, you are less apt to act impulsively and take your life or go down a self-destructive path.

Anyone, anywhere, can go out on the land—and at some point in history, we all did this. But things changed, especially in the south, when urban settings were created. Most people lost that ability to connect to nature, to its food source and to each other. So connection to all these things is an important step. Inuit have maintained that; we still have it; we try very hard to pass it along to our children.

I remember my brothers building snow houses, illuvigait—works of extraordinary ingenuity that showed the impressive engineering skills of our people. Properly made, they can withstand the weight of a polar bear atop them without collapsing and are warm enough to sleep in, or for a mother to birth and nurse her baby. Elijah and Charlie got quite good at carving the blocks of snow and assembling them to make the shelters.

For too long, we have been asking the world to stop bringing harm to our way of life. For too long, the world has responded that it is too expensive to stop bringing harm to our way of life. But one thing I’ve learned—which may equally apply to anyone, Inuit or not—is that putting a human face to all of this is absolutely necessary.

We defend what we love: our land, our ice, our language, our culture, the future for our children. I’ve noticed that as we’ve tried to protect our Inuit hunting culture and its ice, we’ve also, as a natural consequence, been helping to save the planet. We can no longer only see climate change as a question of politics, economics or science. Are you finally listening?

This essay is based partially on excerpts from Sheila Watt-Cloutier’s memoir, The Right To Be Cold, published in 2015 by Penguin Random House.