Illustration by Dushan Milic.

Illustration by Dushan Milic.

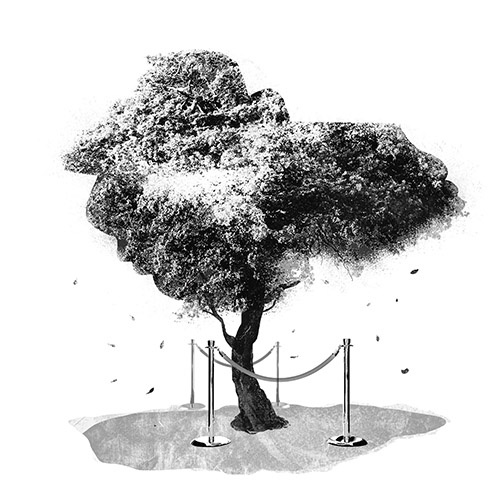

In the Shadow of a Doubt

What was a climate-change denier doing on the board of Canada’s most famous science museum?

From his part-time home in Palm Springs, Jim Silye explains his position on climate change. “Everything has been good, I believe, in green bins, yellow bins, blue bins, black bins, cleaning out the oceans and all that stuff,” says Silye, a retired oil executive and former member of Parliament. But, he says, “don’t use absolute terms to say climate change is man-made.”

For the past eight years—until June 30 of this year—Silye has been on the board of trustees of the Crown corporation that runs three federal science museums in Ottawa. Americans have tried to remove a climate-change denier from their own museum boards, but Canadians have not paid attention to Silye. For him, nonhuman causes—tectonic shifts, balls of fire from the sun, and so forth—could be what’s disturbing the troposphere. “You’re an idiot if you question it, so fine, call me an idiot,” says Silye, seventy-three, “but I’m not just going to shut up and go along with it.”

Silye was one of ten board members at Ingenium, as the museum Crown corporation is now called. Among its properties is the Science and Technology Museum, known for its train exhibit, nausea-inducing Crazy Kitchen and recent $80 million renovation. The other two museums are the Aviation and Space Museum and the Agriculture and Food Museum.

Federal museums’ boards are not supposed to help determine the content of exhibits, and one of their official jobs is to shield staff from political interference. Fellow board members say Silye didn’t influence programming. But when Silye was appointed by Stephen Harper’s government in 2010, the move still brought an extra energy-sector voice to the table in an era when Canada’s traditionally taxpayer-funded museums were welcoming more private money.

Canadian cultural institutions, much like everything else in Canada, pride themselves on a practical, collegial, unglitzy oversight system. There’s “a mix of political colours around the table,” and people “behave like mature grown-ups, not cheerleading squads,” says Victor Rabinovitch, who got to know the system well as CEO of the Canadian Museum of Civilization, as it was then called, from 2000 to 2011. But this collegiality can, in fact, verge into collaboration, Rabinovitch says—it’s just usually seen as a good thing.

Perhaps it’s time to realize how many crucial discussions happen this way in Canada: behind the scenes, politely, with compromises. Perhaps that’s a stumbling block to tackling something as drastic and demanding as environmental collapse.

In 2011, Ingenium launched a project called “Let’s Talk Energy” that included school lesson plans, two travelling photo exhibits and a panel discussion about energy options and “the changing climate.” It showed adaptation to climate change, as well as technologies to mitigate it. Silye says he did not oppose these programs but rather told fellow board members that the programs shouldn’t conclusively state that carbon is the culprit.

“One time, at the end of the agenda, somebody said, ‘Jim, do you really believe this, or are you just being the devil’s advocate?’” Silye recalls. He assured them he was not merely being a controversialist. Working in oil, he saw core samples with volcanic ash from when dinosaurs ruled the earth, which he says shows “that catastrophic climate change occurred 600 million years ago, when man wasn’t even on the earth.” He hasn’t read anything that’s convinced him people are the problem now. Although most scientists agree that climate change is man-made, Silye notes there are still scientists who don’t. And when it came up on the board, his fellow members would tactfully move on to the next topic.

“Everyone would just chuckle and laugh: ‘Uh oh, don’t let Jim get started,’” says Silye.

After a career as a professional football player, then a second one in the oil and gas industry, Silye ran as a candidate for the Reform Party in 1993. He came to know Harper, and the two sat in Parliament for Calgary at the same time. Silye left office in 1997, returned to oil exploration and retired in 2007.

When Harper was prime minister, Silye says, he told one of Harper’s aides that he would be interested in having “something to do,” a way to serve the country. After each federal election, the new government gets to appoint citizens to boards, commissions, agencies and tribunals. Silye says, “I didn’t want to just read books and golf all the time.”

He says he didn’t specifically ask for a museum board position; he privately wished to be appointed to the Competition Bureau. But he was named to Ingenium, sitting with, among others, a chemist from New Brunswick, a retired university dean from Manitoba and a British Columbian woman who has helped fundraise millions of dollars for cancer research and salmon conservation.

Midway through Silye’s time on the board, while living in Arnprior, ON, he published an op-ed titled “Climate change is not a man-made phenomenon” in the Arnprior Chronicle-Guide. “I had a few of my friends just say, ‘Good article, Jim,’” says Silye. “Nobody else wrote a letter to the editor saying, ‘This guy’s out to lunch.’”

Former board members say Silye didn’t dampen museum plans around climate. “The board was in support of the exhibitions for climate change, period,” says one, David James Cohen, a Montreal real-estate investor. Glen Schmidt, a retired oil executive, said board views didn’t matter, anyway. Trustees “might express opinions, but they didn’t have editorial control,” he says.

Ingenium told Maisonneuve that Silye’s influence on its exhibits was nil. The board “is made of a diverse group of individuals with varying opinions,” the organization said.

Past exhibits, though, have not been immune to other forms of outside influence. The Let’s Talk Energy program was sponsored in part by the energy sector, including the Imperial Oil Foundation and the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP). As Maclean’s magazine reported in 2011, this “pervasive influence” shaped the project. One email from the then-president of CAPP, obtained through an access to information request, suggested more attention be paid to oil’s importance to the Canadian economy. The museum’s communications director replied directly, telling the funder he agreed.

While Ingenium’s exhibitions don’t present climate change as a debate, the manager who oversaw the Let’s Talk Energy program doesn’t dismiss Silye’s doubts. “I’m sure there are people who have that opinion,” says Jason Armstrong. “It doesn’t mean that their opinions aren’t valid. I just think that they’re not backed up by scientific consensus, and personally my opinion is that, as a science and technology museum, we look at what the latest science is telling us about any issue we discuss.”

But the museum doesn’t always seem to reflect scientific consensus. The United Nations panel that released last fall’s milestone report—the one that warned we have twelve years to avoid catastrophe—said doing so will take “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society.” Yet just one of eleven permanent exhibits at the museum focuses on climate change, and it doesn’t urge visitors to change their habits.

That’s a happy medium, Armstrong suggests. “We might talk about the impacts of, say, fossil fuels,” says Armstrong, “but we don’t put a message in that, you know, you should therefore give up your car.”

Silye’s position is a reminder that Canada’s museums and galleries are subject to political as well as corporate whims. There have been some glimpses; in 2009, the Harper government shut down a planned national portrait gallery, a pet project of the Chrétien government. Lilly Koltun, who had already been named its director, says construction workers were gutting the site’s wiring and plumbing when “it became quite clear…that it was the end of the road.”

The following year, the director of the Canadian War Museum quit his job after the museum, under political pressure, censored some wording. The spat was over an exhibit that questioned Allied actions in WWII; it said the value of a bombing campaign against Germany was “bitterly contested.” Senators and veterans complained, and the museum revised it to say that the bombing, “an important part of the Allied effort that achieved victory, remains a source of controversy today.”

Board members, in their own way, “are potentially important conduits to the political side of government,” says Rabinovitch. It’s often helpful: they can garner support for big projects, including the rebuilding of the Museum of Science and Technology, which the board chair championed. And there are rare cases where they’re instrumental in developing exhibits, as when the former Museum of Civilization put together the groundbreaking First Peoples Hall with the advice of several Indigenous board members.

On the other hand, there’s also the odd board member who implies his or her political access “could affect the annual appraisal of the CEO,” Rabinovitch says. And in recent years, he says, as Canada has become more politically divided, there’s been a bit more distrust on cultural boards, a few more “extreme views.”

In the United States, museums tend to receive much more private funding—but Americans also seem better at refusing to tolerate troubling influences. In 2015, scientists wrote an open letter to several New York museums, singling out the American Museum of Natural History. They pointed out that billionaire David Koch served on the museum’s board of trustees but had donated $67 million to organizations that oppose climate science. Koch left the board in 2016 after the public outcry. In Canada, one similar effort failed: a 2017 campaign protesting CAPP sponsorship of Canada’s Museum of History, which garnered thousands of signatures but led to no action.

Sometimes it’s almost as if museums forget their own power, suggests Robert Janes, founder of the Coalition of Museums for Climate Justice. “So many museums judge their quality and their importance on how many people come through the door, what kind of restaurant you have, how much junk you sell in your shop,” he says.

But what other institution, he wonders, has the same mix of historical consciousness, creativity and public trust? His coalition calls for museums to urge visitors to reduce their carbon footprints, and he believes the main obstacle in their way is that they don’t want to alienate potential sponsors. “Museums are traditionally just used to sitting on the sidelines, and that attitude has to change,” he says.

Silye himself continues to say he is not a denier but rather a debater. He welcomes rebuttal, he says. If you can “back it up with some facts—believable facts, not debatable facts—then back up your facts, and good luck to you.”