Taking the Wheel

Politicians praise climate-conscious teenagers like Rebecca Hamilton. But what she really wants is better public transit.

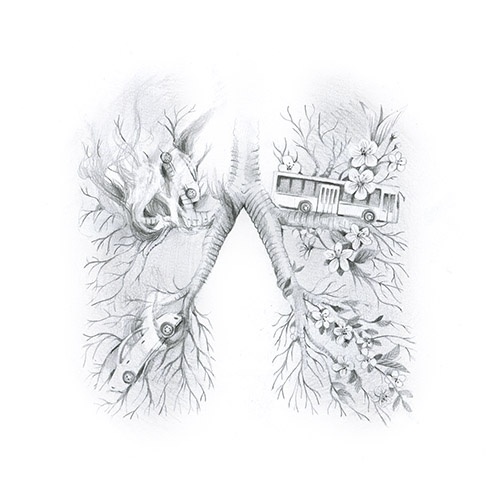

The climate crisis, to me, comes as fire. Growing up in Vancouver, the summers of my childhood meant climbing in the local park and eating sunset picnic dinners at the beach down the road. But I’m now seventeen, and that’s just a memory. Summer is wildfire season, the weeks when venturing outside means the suffocating grip of tree ash in my lungs.

What scares me most about those long days of hazy skies is that feeling of being trapped. When the stars at night and the house down the street are masked by the wall of brown, I feel the same way I do when I think about the future. We have no idea what our world will look like twenty years from now. The horizon of my future is obscured by a haze of uncertainty.

Young people like me have grown up understanding that we are in an emergency, and it’s confusing to see no action that matches that urgency. We are finally done with accepting this disconnect. We are, with a student movement spreading around the globe, striking from school and taking to the streets to show what acting with urgency looks like. I remember the power I felt at my first strike in Vancouver, when dozens of us crowded into the office of our environment minister to ask why his emission reduction targets didn’t align with science.

He appreciated our efforts, he said, before moving on to a disappointing answer: the all-too-common “I agree with you, but...” He said we needed to be realistic.

I am being realistic. And there’s one solution in particular that I want to see: fixing transit. Why this? Because I believe dramatic action will not just prevent future catastrophe but also make life better today, and creating abundant public transit is a shining example of what I mean.

Imagine what we could do with the space previously dedicated to parking lots and six-lane freeways. Imagine if the roar of traffic was replaced by the soft glide of electric buses. Imagine if families struggling to deal with rising living costs no longer had to devote up to 20 percent of their income to their cars, like the average middle-class Canadian household. Imagine, simply, if we spent our commute time having conversations or reading books instead of stuck alone in traffic.

To older generations, this change may seem impossible or even terrifying. As a teenager, I find it exciting. This is why young people have a crucial perspective in society’s necessary transformation: we are still in touch with our imaginations. We understand that the status quo is mutable. We are awash in possibilities.

What if every neighbourhood, town and province across Canada were connected by affordable rail and bus lines? Our country is so proud of having figured out how to extract poison from the tar sands, supposedly the biggest industrial project on earth; we must now pool our collective brilliance to design solutions for the biggest challenge humanity has ever faced.

First, we need all levels of government to invest in getting more buses on the roads. To achieve any public transit goals, more people need to starting using the system. A recent, expansive McGill study found that the best way to do that is to run longer service hours.

Those buses need to be electric, too, because we have a single decade to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions. And we can afford it. According to a 2016 report by Electric Mobility Canada, e-buses’ higher upfront cost is generally offset by their lower maintenance needs and fuel fees. They will become even more economical as the industry is developed. Pilot projects for electric buses are underway in Edmonton, Montreal and Toronto, and more cities should do the same.

We also need more dedicated bike paths and bus lanes. In Birmingham, UK, creating extra bus lanes led to improved service and a 30 percent increase in ridership. We need our cities to reflect scientific reality: the way we allocate space on public roads must demonstrate that CO2 reduction is the priority.

But even that emission reduction is not the real accomplishment. A push for public transit would challenge an all-too-common narrative: that the climate crisis is the fault of our individual actions.

For too long, the story of the breakdown of natural systems has been followed up with one directive: to change our light bulbs and drive less often. This narrative frustrates me, because it makes environmentalism seem like a sacrifice rather than a celebration. I fight for the climate not just because I am too terrified of the alternative, but because I love the beautiful world we are creating.

Instead of us each labouring individually to carve out sustainable lives in an unsustainable system, we can combine our efforts to create a massive collective shift. Instead of desperately swimming against the current, we all need to come together to change the direction of that current.

Public transit would help get us there; it allows us to practice an essential shift in our culture. We need to move from road rage to giving up seats to elders. We need to learn patience and to understand that not everything is within our control. Ultimately, we need to create a world that centres abundant life over exponential GDP.

In the climate strike movement, a key message is that climate policy may be complicated, but the decision to prioritize it is not. With a federal election coming up, pay attention to the transportation platforms of candidates. Do they envision a system that prioritizes humans or metal boxes on wheels?

Politicians like to get caught up in the minutiae of the feasibility of specific schemes. They like to act as though our futures are bargaining chips that can be traded in for short-term approval. We young people know that their interminable negotiations boil down to a single question: will you put out the fire, or watch as the world burns?