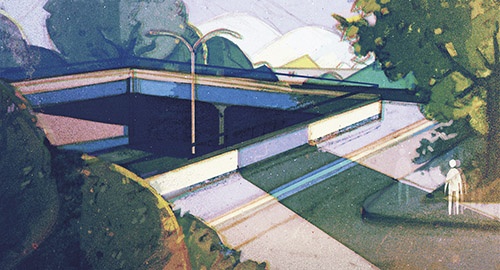

Illustration by Sarah Gonzales.

Illustration by Sarah Gonzales.

Reading the Signs

He said he’d leave if the Parti Québécois’ Charter of Values passed. It was the fall of 2013, and we were sitting in my living room watching the intense political debates happening around then about the charter. Both of us had just entered new, unanticipated life stages. My friend had been diagnosed with cancer. I had a baby rolling around on the rug, pulling the cat’s tail, oblivious to the pundits on TV discussing a law designed to determine who would be allowed to teach her, and the religious symbols those teachers could wear.

He would find it painful to go, he said—to face a diagnosis in some other city. It would be less painful, though, than staying in Montreal, a place he adored even as it became increasingly divided. Illness or no illness, he couldn’t tolerate the spirit of what was happening. As a man of colour who had confronted discrimination. As a man who had lived and worked just about everywhere, but had finally chosen Quebec as his home. Then the cancer went into remission. So did talk of the law.

But before long the cancer spread to his liver. Then, a few years later, clusters of mutated cells metastasized everywhere. Inoperable tumours usurped the strength that his body should have regained after chemo, radiation and finally immunotherapy. God knows what other treatments he refrained from telling us about. To protect friends, or himself, from our fears.

Another election, and more talk of religious symbols. But this time, with my friend’s health suddenly taking another downturn, it was too late for him to think about moving. I rented a new office near his apartment on rue Parthenais, secretly hoping it would give me a legitimate excuse to check in every day. I loved him deeply, platonically, and I would have done anything to help. I carved out elaborate fantasies about prolonging his future: he would get well enough to meet a woman who deserved him. They would have a child of their own. We would all walk together through Parc Lafontaine with our strollers. Go to the wading pool. The bouncy castles in the Old Port. Anywhere at all.

In reality, he was secretive, telling me nothing about his love life or plummeting sperm count. I spied online to glean these details. He volunteered for a group for men with infertility, a side effect of cancer treatment. A hospital newsletter quoted him saying he was terrified of putting a lover through the ups and downs of disease.

By the time the Coalition Avenir Québec introduced the new religious neutrality bill in the spring, I was sure there would have been more obvious signs, portents, augurs to prepare me for my friend’s demise. I invited him to a party; he declined. Treatment that day. I’ll be sleeping like a baby! he emailed. Five days later, he was dead.

I sat in my office until midnight, refreshing the webpage of his online obituary over and over, praying this was all a cruel joke. I stood in my office stairwell, at a window overlooking Parthenais Street where it meets Masson Street, an industrial-looking corner with a trade school and train tracks that seem to lead nowhere. I made myself believe that I saw him, resurrected, shuffling from pain but coming to visit me, crossing where Masson suddenly turns into multiple lanes.

I searched for signs of my friend everywhere in the city. I visited a Shiatsu therapist in a dilapidated building on Pine Avenue. She pressed her hand on my stomach as I sobbed, encouraging me to read Carl Jung and to try talking to the dead. Many nights I lay in bed next to my husband, silently pleading with our friend to answer us. Was he safe on the Other Side? I kept having the same agonizing dream: him standing on my stoop, ringing my doorbell. I couldn’t answer. I was paralyzed.

Two months after the secularism law passed under the new government, there was finally a memorial at a private club. It was near the airport, with bucolic gardens. How fitting that as planes flew overhead, we gathered in a Victorian sitting room, eating canapés, watching a widescreen TV, a photo montage: our friend getting his pilot’s licence, him cycling, him—an ex-Seventh Day Adventist—handsome and wearing a yarmulke, smiling in a synagogue with friends I didn’t know.

Had he converted? asked someone from out of town, surprised.

No. Yes. Maybe. Who knows, I said, as the slideshow rolled on, the airplanes soaring above us, in a city emptied of signs down below.