Illustration by Josianne Dufour.

Illustration by Josianne Dufour.

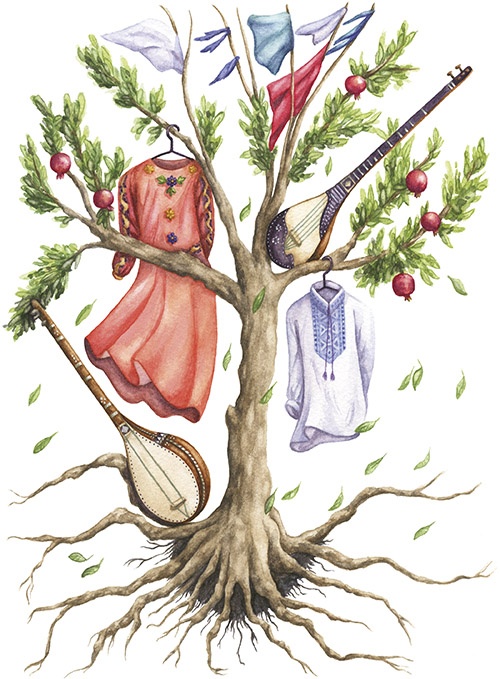

Living Prayers

China is attempting a modern-day genocide, but Uyghurs living in Canada won’t let their culture be erased.

A woman named Ayhan watched about forty children climb onto a stage in a Mississauga community centre one Sunday last summer. She felt nostalgic; she recognized their clothing from her own childhood. The kids wore white kaniway könglek, shirts with colourful embroidery cross-stitched along their necklines, plackets and cuffs, and some had golden-trimmed square caps called doppa.

The children began singing two national anthems: Canada’s and that of the East Turkestan Republic, a former country in central Asia. The land is home to the Uyghur people, who twice succeeded in winning short-lived independence from China in the early twentieth century. Now, with those borders long dissolved, they live in the northwestern Chinese province of Xinjiang. Ayhan is from there, but she can’t go back.

The anthems marked the start of the 2018 graduation ceremony of the Uyghur Canadian Learning Centre. On Sundays, Uyghur children from all over Toronto and its suburbs spend several hours there studying the language, cultural practices and history of the Uyghurs, a largely Muslim, Turkic ethnic group. After the anthems came performances, including a dance by a handful of girls wearing blue dresses patterned with iridescent streaks. They were made of ätläs, a tie-dyed silk that symbolizes Uyghur identity.

Ayhan felt a twinge of regret. She hadn’t enrolled her twelve-year-old son and ten-year-old daughter in the cultural school because they live in the northeastern outskirts of Toronto, while the small mosque that then hosted the school is in Mississauga. It would have been a long drive. But watching a teacher hand out graduation certificates, Ayhan made up her mind. At least I’m not in an internment camp, she thought. I can travel half an hour to bring my children there once a week.

In early 2017, international media began reporting that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was building countless internment camps across Xinjiang as part of its broader campaign to force Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities to abandon their cultures. About 1.5 million members of these groups, most of them Uyghurs, are now in the camps. There are only around twelve million Muslim minorities in Xinjiang, and about eleven million of them are Uyghurs. The CCP is bent on remolding them into its ideal citizens: conformist, patriotic and culturally Han Chinese.

This “conversion,” as the CCP calls it, is all the more traumatic because the party wants these citizens to be secular, while a sense of the sacred permeates Uyghur culture. For centuries, Muslims in the deserts and oases of what would become Xinjiang have created and made pilgrimages to innumerable mazârs—holy sites, mainly shrines and mausoleums—to honour and supplicate the local Islamic saints. These saints were once holy warriors and scholars, kings and poets, mystics, miracle workers. Were you to visit the mazârs, like the photographer Lisa Ross did for the book Living Shrines of Uyghur China, you’d see the desert-weathered but colourful offerings and markers of prayer left by pilgrims: scarves fluttering from wooden poles, goat horns, dolls made of interwoven fabrics that resemble stick figures. You might hear the songs and chants of pilgrims layering over one another. Ross has described the mazârs as places where “spirit vibrated” and “became all-consuming,” and Rian Thum, a renowned historian of Uyghur society, has called them “the landmarks of Uyghur history.”

Islam structures Uyghur life in more quotidian ways, too. Many houses have a mihrab, an ornate, arched niche that points to Mecca, towards which Muslims pray. These houses are often centred around a mosque, the heart of community life. Music is also often steeped in the spiritual, such as the Twelve Muqam, a centuries-old set of songs, poems and dances that draws huge crowds. Parts of it closely resemble the prayers of Sufi mystics.

Now, Uyghurs around the world are fighting to keep this culture alive by passing it down to their kids. Schools like the Uyghur Canadian Learning Centre operate in countries as far-flung as Australia and Norway. In Canada, preserving Uyghur culture is an especially formidable undertaking, since there are only about two thousand Uyghurs scattered across the country. The cultural school was founded in 2016—the year before the camps in Xinjiang came to light—because parents wanted to prevent their kids from being totally assimilated into the mainstream culture of the GTA. But dismay over what is happening in Xinjiang has since caused its enrollment to more than triple from its initial twenty-five students to seventy-eight, as of late 2019. Branches of the school have opened in Montreal, Calgary, Vancouver and London, Ontario. The school has written its own Uyghur-language textbooks and is trying to recruit Uyghur scholars to write more advanced materials.

“We all know that we know how to appreciate things only when we start losing them,” Ayhan told me.

The internment camps in Xinjiang are likened to hospitals in party documents and state-sanctioned media—a comparison that is easier to see if you overlook their barbed-wire fences and guard towers. Inside them, prisoners commonly compared to psychiatric patients must follow a regimen of activities portrayed as purifying—activities that “cleanse hearts” and “wash brains,” in the words of the party. In reality, prisoners are forced to memorize over one thousand Mandarin characters, sing songs praising the CCP, renounce Islam, eat pork in violation of Islamic dietary law, and publicly confess past “crimes,” like studying the Quran.

Punishments for perceived disobedience allegedly include solitary confinement, beatings with electrified batons and even having fingernails torn out. There have been accounts of prisoners being forced to take pills thought to cause cognitive impairment and perhaps infertility. Rape is reportedly widespread. People have died in the camps as well. One Uyghur exile, who became the imam of the small mosque in Mississauga that hosted the cultural school, told me that his mother died in one of them during “questioning.”

This is all happening partly because the CCP views the Islamic cultures of the Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities as breeding grounds for “ideological diseases,” predisposing people to “religious extremism and violent terrorism.” The party is consequently waging what it calls the “People’s War on Terror.” The current government crackdown began in 2014, after some Uyghurs participated in riots and attacks against police and Han Chinese civilians. But these sporadic acts of violence were a predictable consequence of Chinese colonialism.

The CCP crackdown has since become an all-encompassing dragnet. Virtually omniscient mass surveillance—relying in part on artificial intelligence scanning footage from ubiquitous cameras—singles out people whose behaviour supposedly suggests they are “infected” with an “ideological cancer,” as the CCP sees it. Most people are targeted for acts as innocuous as growing a long beard, which has spurred Muslims in Xinjiang to largely refrain from expressing their faith and other aspects of their cultural identity. Police officers, about as omnipresent as the cameras, detain people flagged by the surveillance system and send them, without trial, to one of the internment camps.

As the CCP fills the deserts of Xinjiang with the camps, it demolishes those built structures that imbue the landscapes of Xinjiang with cultural significance for the Uyghurs and other minorities. The government has destroyed over two dozen sacred sites, including an eight-hundred-year-old mosque. Those mazârs that have not been razed are missing the usual offerings and markers of prayer, and the devout don’t dare go on pilgrimages to leave new ones. Media has reported that the CCP is also forcing Uyghurs to deform or fill in the mihrabs in their homes—Radio Free Asia described a video on social media that seemed to show a Uyghur woman smashing a mihrab in her ceiling with a shovel.

Timothy Grose, an American expert on China, says this is all “essentially laying out a new blueprint for life.” Over a million CCP officials have invited themselves into Uyghur homes for prolonged stays to “educate” their “little brothers and sisters” about the ideology of Xi Jinping Thought and monitor them for any hints they are unpatriotic or resentful. Meanwhile, the children of Uyghurs in the camps grow up in state-run orphanages speaking Mandarin and living as Han Chinese children would. The professor James Leibold has also documented how the CCP is incentivizing Han Chinese men to marry Uyghurs to “slowly breed out Uyghurness” and how the party has implemented a plan to lower their birthrate.

The oppression of the Uyghurs therefore matches with chilling exactitude the original conception of genocide, as defined by the Jewish jurist Raphael Lemkin: it is a “coordinated plan” targeting a group that is meant to bring about “the forced disintegration of political and social institutions, of the culture of the people, of their language, their national feelings and their religion” so that “these groups wither and die like plants that have suffered a blight.”

Ayhan told me about her life in Xinjiang as we sat at a table in the locker-lined hallway of a public high school in Brampton. It was March 2019, and Ayhan had become a board member of the Uyghur Canadian Learning Centre, which had by then outgrown the small mosque in Mississauga. She had spent the early afternoon greeting parents and children at the table before they entered a wing of the school where classes were being held. She wore a necklace with a golden pendant on which bas-relief letters of Arabic calligraphy spelled the name of God, Allah.

Ayhan immigrated to Canada nearly fifteen years ago. As a lecturer at a university, she had felt increasingly pressured to speak in Mandarin to her Uyghur students and to encourage them to speak Mandarin in their dormitories, she said. CCP efforts to culturally assimilate the Uyghurs can be traced back to the late 1950s, and at the time that Ayhan was teaching in the early 2000s, Beijing was already ratcheting up restrictions on expressions of Uyghur cultural identity. She felt forced to make a choice: “Either I close my eyes and swallow all the pain, or I have to move.” She couldn’t bring herself to help strip her students of their culture. “When you lose it, it’s just like you’re losing a part of you,” she says. “You will not feel whole again.”

Ayhan now feels like she is missing another essential part of herself, however. When we spoke, it had been months since she’d heard from her family in Xinjiang. This experience is common among Uyghurs in the diaspora. If their friends and family in Xinjiang aren’t already in the camps, communicating with people abroad increases their chances of being sent there, and so they ignore loved ones outside the country. “It feels like a tree that is cut off from the root entirely,” Ayhan says. “My root is cut off completely. What happens if you cut off a root of a tree?”

Ayhan got involved at the school in Mississauga partly for the sake of Uyghur-Canadian kids and their immediate needs. She had noticed that they sometimes felt self-conscious and even ashamed of how they stood out. These feelings are not uncommon among immigrant children, but they can be particularly acute for Uyghur-Canadian kids due to the small size of their community and the difficulty of explaining who the Uyghurs are. Ayhan recalls that her daughter, when in senior kindergarten or grade one, broke down crying the first day back from summer holidays because her teacher had asked students to introduce themselves and say what their background was. She was overwhelmed by the pressure of explaining that her family comes from East Turkestan, better known as the Chinese province of Xinjiang—but that her family is not Chinese. “Teaching at the Uyghur school is to help our children to find out who they truly are,” Ayhan says.

But that wasn’t the only reason. “This beautiful piece of culture, this beautiful piece of civilization, is about to be wiped out,” she says. Teaching is “another way to say ‘no’ to that.”

Ayhan has taught several language classes. She devised learning exercises like giving her students pieces of Lego so that they could create rectilinear versions of the swirling letters of the Arabic alphabet, the script of the Uyghur language. She also helped arrange dance lessons for the boys and threw herself into fundraising to buy Uyghur dance outfits from Kazakhstan. “Step by step, we are becoming better and better,” she says.

Ayhan gave me a tour of the school. In one classroom, girls practiced a dance that required them to hold paper plates—substitutes for the ceramic ones that professional Uyghur dancers use. They made sly, goofy faces at each other. When their instructor made them repeat a sequence of movements, pushing them to be more synchronized, there were even displays of solidarity, sighing and eye-rolling. During a break, they busted out gymnastics poses. In another classroom, the students were more subdued. A middle-aged woman, her grey hijab decorated with a print of white flowers, read in Uyghur to boys wearing black kaniway könglek.

One of the boys studying Uyghur was the nine-year-old son of a man named Varis, who lives just north of Toronto. He says that the school has not only increased his son’s fluency in the language but has changed him in more profound ways. Before, the boy had listened to the English-language music of his public school peers, not liking his father’s Uyghur music. Now he dances to his dad’s songs. He once asked his parents to make him sandwiches to bring to school for lunch so that he could be more like his friends. But he began refusing to eat them, preferring the Uyghur cuisine—meat pie, hand-pulled noodles, dumplings—that his parents wake up an hour early each morning to cook. “When we learn our culture, we feel we are very close to each other,” Varis says. This is true of all cultures, he says, but Uyghurs are especially tight-knit.

“The relationship between neighbours in our culture is valued a lot,” Ayhan told me. A young Uyghur leaving home for university could normally expect dozens of neighbours to bid them farewell, bringing them gifts of dried figs, nuts, pastries and money. “Here, I live in my condo for five years. I don’t even know what’s the name of my neighbours,” she said.

“When you belong to a certain culture, you feel more confident, and when you are more confident, you can flourish,” Varis says. “It’s like a big tree—if it has strong, healthy roots, it can live for longer, right? If not, you will be gone among all the other stuff.”

Some students had become skilled enough dancers to perform at a June 2019 concert called “Endangered Culture,” a fundraiser for displaced Uyghur children in Turkey. The venue was the Noor Cultural Centre, a hub of Islamic community life located in northeastern Toronto. The room serving as the auditorium was packed, mainly with Uyghurs, but also with many Muslims of different ethnicities who had come to support them.

A recently released song entitled “Seghindim Weten” (“I Miss My Homeland”) was playing on repeat, and the sounds of Uyghur instruments mingled with the overlapping conversations of the audience. There was a näy, similar to a flute, plaintively fluttering up and down in pitch. The timbre of what was likely a yayli tämbür, a long-stemmed instrument played with a bow, resembled that of a cello but with a sharper edge, creating a sense of forsakenness. An Uyghur pop star sang: “I look to the birds and wonder what they search for / Perhaps they have flown across the sky of my homeland.”

Once the concert started, six tween girls danced onstage, their green dresses decorated with a yellow and orange pattern shaped like spiky foliage. This motif is known as anar güli, “pomegranate flower.” The school’s dance instructor performed several dances, including one where she spun around so fast that her green skirt billowed upward even as she held plates in her outstretched hands and balanced a stack of bowls on her head. One singer had travelled from London, England, and had only rehearsed for a couple of hours with two men playing the dutar, a two-stringed lute, before they performed Uyghur folk songs, the audience clapping along.

I spoke with the singer, Rahima Mahmut, two months later. She has lived in London for close to twenty years, but that hasn’t stopped her from becoming acquainted with some of the best-known Uyghur intellectuals and cultural elites—who are now in the camps. I was therefore half-expecting her to talk about Uyghur culture from the detached perspective of a highbrow critic. Instead, she invited me into the intimacy of her childhood.

“From the time I was born, I remember, I was woken up by my father’s reading of the Quran,” she told me. She recalled his deep voice rising and falling “in waves,” elongating certain notes, as he sang “Surah Yasin,” which many Muslims consider to be the heart of the Quran. “It’s a very beautiful prayer,” she said. Mahmut grew up in a big house separated from the road by an apple orchard, providing her “very large, religious, musical family” enough privacy to recite the Quran and pray together even as the Cultural Revolution crushed religious life around them. Mahmut’s father used to warn her that if she told people her family prayed, or if she recited the Quran verses she had picked up, he would go to prison. But amidst the trauma of the times, awakening to her father’s recitations filled her with a “very calming, joyful, spiritual feeling.”

Her earliest and fondest memory was of waking up at 4 AM during the winter and accompanying her father on a two-hour donkey-cart ride over secluded country roads to a city. There, he would surreptitiously sell apples in bulk before sunrise to avoid being arrested as a “capitalist-roader.” For the entirety of the trip, in the pre-dawn stillness, her father would recite the Quran.

“For people to live,” food and shelter are not enough, she says. People hunger for another sort of sustenance. “You cannot enjoy life without feeling the satisfaction of your soul.” Some days, she plays recitations of the Quran on YouTube as she goes about her day, finding it “so calming, and so spiritual.” She listens to Uyghur folk songs while doing housework or cooking—the same songs her mother used to sing during her own housework—and “even though my body’s here,” in London, she says, “my mind travels to my childhood.” Earlier in the day, before we spoke, she listened to a folk song about apples ripening. “It takes me back to those apple orchards where I grew up,” she said. “Imagine if, from my childhood, I didn’t have that culture, didn’t have that religion, [and] it was completely taken away from me. I would be a completely different person.”

For Darren Byler, an anthropologist who studies the Uyghurs, “an erasure of a person’s identity, of their personhood as an individual but also as a [member of a] collective,” is the essence of cultural genocide. “Self-determination does not necessarily mean establishing a nation-state,” he said. “It means having control over your story as a people…be[ing] the author of your own story. The Uyghurs are on the brink of not being that anymore.”

Children wearing white kaniway könglek, ätläs dresses, doppa and light-blue collared shirts—the uniform of the Uyghur school in London, Ontario—ran past tables where adults sat chatting around plates of sangza, stacks of tightly coiled, fried noodles. Some of the kids mounted a stage at the back of the large room in the Mississauga community centre where the school was hosting its graduation ceremony in June 2019, a year after the one Ayhan first attended. Kids leapt from the stage onto the floor and ran off.

There was a play based on an ancient folktale in which a boy carrying a toy sword, shield, bow and quiver saved a girl from a witch—a girl wearing a white wig and black garbage bag. A boy recited “Surah Al-Fatihah,” the opening chapter of the Quran, his voice reverberating around the room. Girls danced with paper plates.

Near the end of the ceremony, a group of older boys, including Varis’s and Ayhan’s sons, walked into the middle of the room wearing dark blue robes lined with an elegant golden trim as drums pounded and a sunay, a high-pitched horn, blared. Smiling, they began a classic Uyghur dance based on a set of Sufi rituals: diving forward, swiping an arm down towards their feet. They gathered in a circle and kneeled around one boy who twirled like a whirling Sufi. Like the girls before them, they followed the choreography relatively smoothly, but at times some dancers got out of sync and glanced at their peers before hastily adopting their poses. These cultural dances still seemed a bit foreign to some of the kids, like hand-me-downs that they were still growing into.

Varis watched his son dance from the cheering crowd. “I got goosebumps,” he told me later.

Shortly after the ceremony ended, upbeat Uyghur pop music started playing. Soon the adults and children were gracefully dancing together, twisting their torsos, twirling. Varis held his small daughter in his arms and grinned as he looked at his son, dancing nearby with other boys, still in their blue robes. In the background, a toddler in a pink tutu wobbled across the stage, chased by an older girl. A few kids took turns making noises into a microphone. Ayhan, wearing a doppa embroidered with red flowers, looked on with pride.

She later teared up as she recalled the moment. The dancing illustrates how “this culture, it gives us strength and hope,” she said, her voice strained. “What we are going through is unbearable, but we still dance.”