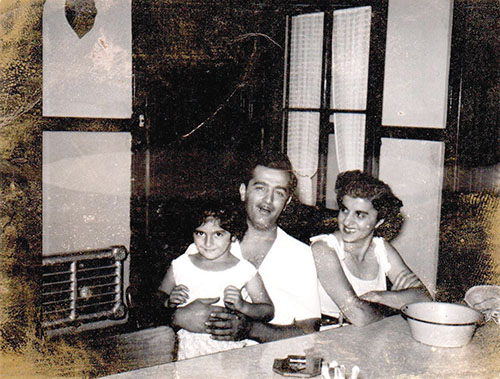

The author’s Sito and Jido, or grandmother and grandfather, when they were engaged in the late 1940s.

Photo courtesy of the author.

The author’s Sito and Jido, or grandmother and grandfather, when they were engaged in the late 1940s.

Photo courtesy of the author.

Living Legacy

As an adult, Montrealer Christine Estima discovered a buried truth about her family—and her city and country.

For most of my life, I didn’t know I was Syrian. It wasn’t a big secret; no one was actively keeping it from me. I just missed all the signs. I was close with my Sito, who was a loud-and-proud Lebanese woman, so it never occurred to me that my Jido—who passed when I was a baby—might be anything other than Lebanese.

The hints consistently went over my head. My mother insisted we call it “Syrian bread” instead of “pita,” because “pita is a Greek word and the bread originated in Syria,” she swore. But being a Montreal kid who mostly learned the Arabic words thrown about the house phonetically, I thought she was saying “cerean” bread—as in, from cereal. The bread was made from cereal? I pondered.

Every Sunday, we went to church at St. Nicholas Antiochian Orthodox Church on the corner of St. Dominique and de Castelnau streets in the Little Italy district of Montreal, but I didn’t know that the church was originally called the Syrian-Greek Orthodox Church of St. Nicholas. This is the church where I was baptized, where my parents married, and where my grandparents married (Sito and Jido mean “grandmother” and “grandfather” in Arabic), but I didn’t clue in that a Syrian church was actually a massive part of my family’s history. When I finally learned in my twenties that my great-grandfather had been born in Damascus, not Beirut, my mother offered a plethora of information that made my head spin.

Of course, when looking at Lebanon and Syria through the long lens of history, there is a great deal of crossover between the two countries. At many times, Syria and Lebanon were under one banner, one nation, one ruler, one empire. Even recent history—Syrian troops occupied Lebanon all the way up until 2005 after the Lebanese civil war—shows that the border and demarcation between these two ethnicities is a bit muddy at best. When my cousin Salwa was born in Montreal in 1922, the birth certificate issued by the city listed her parents as from “Rashaya al-Wadi, Syria,” except that Rashaya al-Wadi has always been in Lebanon. Her godfather is listed on the same document as being from “Lebanon, Syria.” So it’s no wonder that when I called myself Lebanese, no one in my family went out of their way to mention, “Tsk tsk tsk, you’re also Syrian, habibti.”

Nor had I clued in that Syrians were also a big part of Montreal’s history. In many ways, Arab Montrealers can be ethnically invisible: we can “pass” as white to others, but our ethnicity can be a second thought even to us. Sure, I always knew we were Arabs, but we only spoke English and French at home and led a pretty normal Montreal life: smoked meat was a staple, and daily trips to the Jean-Talon Market for cherries and cantaloupe were expected. Turns out my Auntie Edna and Auntie Elsie, two powerhouse women who helped raise me, were actually born with the names Fadwa and Techla; they anglicized them upon their marriages to non-Arab men. My Uncle Edward was actually Uncle Dawood. And Uncle Shaf was actually, wouldn’t you know it, Uncle Shafeek. Doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue.

The author’s Sito, Jido and mother as a young girl pose as a family in August 1954.

The author’s Sito, Jido and mother as a young girl pose as a family in August 1954.

Arabs, like many ethnic minorities in North America,love to shout from the rooftops when a celebrity is part of the fold. Sure, you’ve heard about Salma Hayek, Paula Abdul and Shakira (and if you’re old enough to remember, Danny Thomas), but did you know F. Murray Abraham is one of us? American Pie star Shannon Elizabeth? Vince Vaughn? Look it up.

Closer to home, Montreal’s late-great René Angélil, husband to Céline Dion, was ethnically Syrian and Lebanese, like me. My mother once casually dropped into conversation that I’m related to Canada’s favourite crooner (and fellow Arab), Paul Anka. My aunt Patsy married Paul’s uncle, George Tannis, and I’m sure they did it theirrrrr wayyyyyy. And then there’s the former premier of Prince Edward Island, Joe Ghiz, who is rumoured to be a distant relative (my Sito’s maiden name was Ghiz).

Despite all of that, there’s a persistent myth that only now are Arabs, and specifically Syrians, flocking to Canada en masse due to turmoil in their home states. Amid the Syrian refugee crisis, some have concluded that “Syrian Canadians” are a new phenomenon, with our people having no historical lineage in this country. In 2015, the New York Times reported that Canadians were overwhelmingly supportive of welcoming Syrian refugees mostly because the harrowing image of Aylan Kurdi, a three-year-old boy who drowned while escaping the war with his family, shocked them into action. Media clippings from the time show that Canadians were obsessed with the tens of thousands of Syrians arriving in Canada. At no point in any of these reports was it mentioned that Syrians have been living in Canada for over a century.

It’s a kind of erasure that sees Arabs as foreign or, worse, “exotic.” And it goes back to before the Syrian refugee crisis, and extends beyond Canada’s borders. In 2010, American writer Alia Malek argued in the Nation that the “utterly foreign” depiction of Arabs in the American mosaic was a “skewed version of reality,” that the Arab huddled masses that flocked to America in the late 1800s “are barely reflected in the historical narrative or in the other ways a nation imagines and celebrates itself.” If they are reflected at all, Malek says, it feels like “a safari,” as these Arabs are “treated as objects of curiosity instead of as a part of America’s complexity.” Another writer, Suad Joseph, wrote in 1999 that the conflation of “Arab” with “Muslim” has made “the diversity of Arabs invisible.” Arabs can also be Christian or Jewish, and Muslims need not come from the Middle East. Joseph argued that the conflations erase Arab diversity by serving “the creation of another difference: the difference between the free, white, male American citizen and this constructed Arab.”

We may be proud of them—but how often have you heard my cousin Paul Anka described as an Arab? Or René Angélil? Or Salma Hayek? They do not fit in with this “constructed Arab” category, and therefore, they are simply not seen as one of us. An entire ethnicity erased.

Many years ago, I moved to Toronto, and suddenly trips to old St. Nick’s church, or even to visit the old neighbourhood, were a distant memory. Sure, I went back to Montreal frequently, but as the years wore on, more immediate concerns became the order of the day and listening to the stories and traditions of the family were pushed farther and farther down my to-do list. And if I’m being honest, maybe I wanted a little distance from my roots too. Racism acts upon each racialized person in different ways: in my case, being bullied as a child for my Arab features had an insidious effect. As a young girl, I lived in a neighbourhood and went to a school populated mostly with Québécois faces (beautiful green eyes, freckles and fair skin), so naturally, I was bullied for my dark features, my thick eyebrows and my olive skin. On a school bus, a boy once said to me, “When you were born, God thought your face was your cunt, so he put hair all over it.” As an adult I did everything I could to blend in, plucking my bushy Lebanese eyebrows until they looked like the square root symbol.

But let’s face it: 2020 has been a year of reckoning. As more BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of colour’s) voices are making their way to the front, we as a society are finally coming to terms with the fact that racism has been the foundation of this country.

And sometimes, when I wake up in the morning, I think about all my ancestors whose existence allowed me to have mine. I wonder what would happen were I ever to come face to face with them in some cosmic fashion. I wonder if they would recognize me in them, or if I would recognize them in me. Would they like me? Would they disapprove of me? Equally perplexing, would I even like them? I decided to take a deeper dive into their story. So I returned to Montreal one cold winter’s day.

The author’s mother as a young woman.

The author’s mother as a young woman.

When I was a little girl, my Sito would tell me stories of how she and Jido met and fell in love in the late 1940s. She was sitting with her girlfriends in a booth at the soda jerk that all the Lebanese girls frequented, near the intersection of Bélanger and St. Hubert streets, and in he walked—dapper, handsome and full of bravado. After introductions and pleasantries were exchanged, he pointed right at my Sito and said, “You, I’m going to sleep with.” Sito smacked him right across his smug face.

“What the hell are you doing, you dumb broad! I’m paying you a compliment,” he barked, holding his cheek.

“Those kinds of compliments, I don’t need!” she snorted back.

A year later, they were married. I used to sit at the foot of my Sito’s bed as she would tell stories of her and Jido together, relishing every detail from their tumultuous courtship. One thing that she never forgot to include was how Jido’s entire family was against their union because she came from a different church. “His father was the priest, you know.”

I would nod along, but I never really put two and two together. Jido’s father, my great-grandfather, was a priest, but I didn’t know he was the priest of St. Nicholas Antiochian Orthodox Church—the Very Reverend Economos Michael Zarbatany who was a pivotal early leader of the very first Syrian Orthodox church in Canada.

The first time I walked back through the doors of St. Nicholas after a twenty-five-year absence, I was struck by the familiar scent of incense that lingered, earthy and raw. A memory of fear suddenly snapped back. As a little girl, I used to be haunted by the images of Jesus Christ, his apostles and his assumption, done in the Orthodox style and adorning every wall and stained-glass window—their eyes seemed to follow me. I sat in the back pew during the end of the liturgy; all the sermons were performed in English, though a few hymns and prayers were peppered with Arabic. Then the entire congregation was invited to the basement for coffee and za’atar bread, a kind of flat bread seasoned with Middle Eastern spices and sesame seeds. I vividly remembered this basement, where as a child I did an Easter egg hunt. Staring at the congregation’s faces, I noticed how eerily familiar they seemed, despite being strangers. I could pick out the features of my Sito and Jido adorning the faces of every man, woman and child milling about. Nonetheless, I felt anonymous there.

When I met the priest and told him I was Michael Zarbatany’s great-granddaughter, he introduced me to a woman who he said knew even more about the church than he did: general secretary of the parish council, Carol Maker. As soon as I shook her hand, I knew I had met her before. As a little girl, sitting in a church pew, wearing my Sunday finest, I’d once been introduced to a kindly old fellow named George Maker who bore a strong resemblance to my late Jido, whose photographs adorned every corner of Sito’s house. I asked George Maker if I could call him “Jido Number Two.” From then on, George Maker was my gramps-substitute. I immediately blurted this out to Carol who, as it turned out, was George’s daughter, whom I had also met that day in the pews. She looked me up and down and marvelled, “God in heaven, you look exactly like your great-grandmother.” Carol provided me with a pile of documentation about my great-grandfather’s legacy in Montreal.

It took me hours to pore over and changed everything I thought I knew about my lineage—and about Montreal’s history. Born in Damascus in 1884, Michael moved to Montreal in 1906 and founded the very first Arabic-language newspaper in Canada, called Ash-Shehab (“The Brilliant Star”). He married my great-grandmother, Beirut-born Mary Attabe, when she was only sixteen, a cultural norm at the time that doesn’t land well in today’s climate. They had thirteen children, one of whom was my Jido, Victor.

Michael was ordained in 1917. The church he ended up leading, originally located on Notre-Dame St. in Old Montreal, ultimately moved to its current location one block north of Jean-Talon and east of St. Laurent. That stretch of Jean-Talon, heading east, is considered the main thoroughfare for the Syrian-Lebanese community in Montreal: both of the city’s oldest Syrian Orthodox churches are there, and around the corner on St. Hubert St. was the Syrian Ladies Benevolent Society.

After a few years, my people began to spread through the province. According to the World Lebanese Cultural Union, “in 1910, Syro-Lebanese immigrants were already established all over Quebec, in Mont-Joli, La Pocatière, Saint-Michel-des-Saints, Rouyn, Trois-Rivières and Sherbrooke among other places.” It wouldn’t be long before large communities would pop up in Ottawa, Toronto, Quebec City, Newcastle, Charlottetown, Picton, and many others.

The community in Montreal flourished; by 1921, it had about 1,500 people of Syrian origin. I instantly recognized the names in old papers. Listed on the board of directors of the Syrian Ladies Benevolent Society in 1932 to 1933 was a Mrs. Akaaber Sayfy. Sayfy’s Grocery, which stood across the street from the famous Jean-Talon Market for many years, was founded by her son, Nick Sayfy. As a child, it is where my family took me to shop for baby vegetable marrow, za’atar spices and vine leaves to make kousa (marrow stuffed with stewed meat and rice), za’atar bread, and yaabra (baked vine leaves rolled like cigars and stuffed with tomatoes and rice).

Food has been a cornerstone for the expansion of Arabs from the Jean-Talon area outwards. In 1978, the Cheaib brothers, new arrivals to the area after fleeing the Lebanese civil war two years prior, set up a restaurant around the bend from St. Nick’s, calling it Adonis. It has since expanded to fifteen different locations across Quebec and Ontario. Syrian restaurant Damas, which is internationally recognized as the best in Montreal and the country, opened its first location not in Little Italy but in Mile End in 2010.

On top of the Arab superstars of cinema and music mentioned earlier, other trailblazers emerged, including a myriad of Lebanese-Syrian politicians: Mark Assad for the riding of Papineau in 1970, Pierre J.J. Georges Adelard Gimaïel for Lac-Saint-Jean in 1980, the senator Pierre de Bané. MP Maria Mourani was the first woman of Lebanese origin elected to the Canadian House of Commons in 2006, for the Bloc Québécois.

But for me, learning about Michael Zarbatany was what really struck a chord. My great-grandfather was a journalist—was that why I always wanted to be a scribe that told stories of the little guy? He also became a Justice of the Peace for the District of Montreal in 1920. In an undated interview for The Saint, a now-defunct newsletter once distributed by the church, Michael’s son Anver, my great-uncle, recounted how his father’s character was tested one day when a farmer, driving a truck with no brakes, collided with Michael’s car. “The farmer asked to be given a chance because he was poor and had no insurance. Father told him to go and forget about it,” Anver wrote. “The farmer, however, wanted to show his gratitude. That night when father came back home, mother got the surprise of her life when she saw ten bags of potatoes being unloaded from the car.”

It’s a cute story that may or may not be true, given that church leaders are often deified in urban legends while they’re still living in order to promote attendance. However, a contemporary newspaper report in the Montreal Gazette recounts Michael’s deep loyalty to the community of Montreal and his role as Justice of the Peace—so deep that it put him at odds with his own son. The story goes that the son, my great-uncle Emile, was wanted by police in 1941 for attempted murder, armed robbery and possession of drugs. He was dragged into police headquarters by none other than Michael Zarbatany. Emile was later convicted of these crimes, and for decades in our family, his name was never spoken again. I only learned of his existence less than five years ago.

The legend in our family is that the Zarbatanys were once gun-runners for the Ottoman Empire, and they took their last name from the very gun they once smuggled: the zarbatan. No one really knows why my great-grandfather was so determined to be the opposite of what his family once stood for, but I’ve heard it said that he immigrated to Canada with the idea that he could pursue his own path in life.

When Michael died in 1960, The Word, the official magazine of the Antiochian Archdiocese, reported that “a telegram was received from Queen Elizabeth II through Her representative, Georges Vanier, the Governor General of Canada expressing the sympathies of the Crown in the passing of this beloved clergyman.” The prime minister at the time, Diefenbaker, plus Quebec’s premier and Montreal’s mayor, all sent condolences. It would seem that in Montreal, Michael’s absence left a scar, but sixty years later his life is just a footnote. Just as unless one were to dig, no one would ever know all these accomplishments were those of a Syrian immigrant.

Michael Zarbatany, the author’s great-grandfather and a well-known priest and Justice of the Peace in Montreal, photographed in the last years of his life, in the late 1950s.

Michael Zarbatany, the author’s great-grandfather and a well-known priest and Justice of the Peace in Montreal, photographed in the last years of his life, in the late 1950s.

Despite all they contributed, early Arab immigrants weren’t exactly welcomed with open arms by white Canadians. In August of 1890, the Toronto Daily Mail printed a description of an Arab ship docked in port. Using the term “Mohammedans,” which was de rigeur at the time, they described us as “like monkeys.” “Impassive,” they wrote. “They never laugh.” “They shrink in terror.” “They drink gin and beer like white men.” Then the article flat out calls us “pariahs…Hindus would not mingle with them.”

With such a bestial description of us, it’s easy to see why we would form our own community cathedrals, organizations and societies. Houda Asal, an academic and author of a recent book on Arab communities’ history in Canada, says among the “hierarchy” of how various immigrants were viewed in Canada in the early twentieth century, Arabs were not nearly as “desirable” as Europeans, but not as denigrated as some. “In effect,” she explained, “they weren’t as badly viewed as the First Nations, Black people, as well as Asians,” meaning Chinese, Indians, and Japanese.

Asal calls this an “intermediate” place. It’s still a nebulous position. It could be said that Muslim Arabs in places like Montreal who wear traditional and cultural garb are more readily identifiable as Arabs. And they are surely ostracized or “othered” more often than Orthodox Arabs like me; there is a privilege that comes with being able to “pass” in a white society.

But this is also a reminder, Asal says, of white colonialism and systemic racism. “The erasure,” she says, “is explained by multiple factors: the difficulty for these groups to have a communal identity for a long period of time, discrimination and stereotypes which pushed certain people within the group to choose integration, but also the media’s negative portrayal.” The state was also repressing certain identity claims, she adds, for political reasons—for example, the Palestinian cause. “All of this didn’t help build a permanent narrative that recognized the contributions of these people to general society.”

Case in point: for my return visit to St. Nick’s, I brought my boyfriend, Gabe, with me for support. As he looked about the liturgy in progress, he commented he wouldn’t even know this was an Arab congregation on sight because so many could pass for “white.” In a predominantly white and Catholic Montreal, we are Arabs, but we’re not “Arab enough” to be classed any differently than a Quebecer. Yet while we are Canadian, we’re not “Canadian enough” because we refuse to drop our cultural and linguistic traditions. That, in 2020, is Asal’s “intermediate” place. And when your ethnicity is invisible, not only are your struggles glossed over but also your successes.

The perpetual and gross myth is that Arabs come to Montreal to make use of its economy and peace, while simultaneously harbouring a deep resentment for Canada, with a goal of living scot-free off the system. This discrimination is still felt—about a quarter of Lebanese-Canadians suffer unfair treatment on the basis of ethnicity, race, religion, language or accent, the World Lebanese Cultural Union reported in 2015. Despite this nefarious narrative, the Lebanese are statistically more likely to find work quickly upon arrival or create the work themselves, often founding businesses. Despite the obstacles they face, Lebanese immigrants find a first job, on average, within thirteen weeks of arrival, said the same report. Nonetheless, the idea that people from an entire culture can innately be double-faced charlatans has cast a dark shadow for decades.

One night last November, now-fired Coach’s Corner host Don Cherry said on air that “you people” come to Canada for the “milk and honey” but refuse to wear the poppy or honour Canadian troops.

I watched the clip of his spiel and thought of those old papers. In reading them I’d also learned more about my Jido, Victor. Victor, growing up, was a scoundrel; his report cards were peppered with reprimands, or with scoldings for being caught smoking. In 1939, when the war came, Victor wasn’t old enough to join the army, but his charlatan proclivities finally matched up with his sense of civic duty; he lied about his age to get into the military. Assigned to the Loyal Edmonton Regiment, he trained in the Maritimes before being shipped off to London, North Africa and Italy. His letters home to his mother speak of his wish to find a nice Syrian girl in London to marry (thankfully that didn’t happen or I wouldn’t be here), trying to prevent his other brothers from joining the war effort, asking for money (the army was slow to pay, and presumably he had spent his wages mostly on tobacco and whiskey), and expressing his frustration at the army censor for curtailing his letters.

He also mentioned that there didn’t seem to be other Syrian troops. When he befriended a Syrian family in London, he wrote at length about it. All signs point to him being one of the few Arabs in the Canadian army, and he probably felt isolated, even amongst friends.

Official telegrams sent to his mother show that he was wounded twice in action. His military records show that, while he was writing home to Montreal claiming he was well, and to “please not worry,” he was actually fighting in the infamous bloody Battle of Ortona in Italy, where the Loyal Edmonton Regiment engaged the Nazis for an entire week, suffering large casualties but eventually winning. Jido, as a gunner, was on the front lines, and as a result was left deaf in one ear, with shrapnel embedded in his back, and an extreme case of shell shock, now known as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. For years after the war, any time a car backfired or the sky produced a thunderclap, he’d dive under the table.

Any family that boasts a war hero has a lot to be proud of, and I am. In fact, when my beloved Sito passed, I inherited my late Jido’s war records, his dog tags, and most notably, his war medals: he received the 1939-1945 Star, the Italy Star, the Defense Medal, the Volunteer Service Medal and the War Medal.

Watching Don Cherry that night, I felt like someone had taken a spoon to my heart and scraped it out until it was hollow. It didn’t even occur to him that the very people he was maligning for supposedly refusing to wear poppies could be serving in the Canadian military as he spoke. (In fact, our Minister of National Defence, Harjit Sajjan, is an immigrant and also a veteran of the armed forces.) It’s impossible to say he meant Arabs specifically when using the term “you people,” but with this kind of racist dog-whistle, it doesn’t matter; I recognized the smear.

I tapped out a tweet: “Don Cherry, my grandfather fought in WW2, he was 1 of the few Arabs in the Canadian army, fighting in the Battle of Ortona, killing every fascist he saw. He came home deaf in 1 ear, shrapnel in his back & shell shocked. He didn’t do all that so you could whitewash war heroes.” I included in the tweet the handsome official military portrait of my Jido in his army uniform—his hair slicked back, familiar thick eyebrows like mine—and sent the tweet out into the ether. I awoke the next morning to see it had caught the attention of thousands of people.

News outlets were itching to hear about my family and my viewpoint. But as I did the live television interviews, seeing the journalists themselves listen with fascination, I began to feel almost like I was a curiosity. Step right up to view the Arab who fought for Canada in the Second World War! Take your souvenir photo of the Arab who is Just. Like. You! After the bewildering media blitz, it dawned on me how much our legacy in this country is underreported, glossed over. And what an awful shame that is. I’d hazard that Montreal and Canada today would be vastly different without us.

A military photo shows the author’s Jido, Victor, in uniform during his service in the Second World War.

A military photo shows the author’s Jido, Victor, in uniform during his service in the Second World War.

There are dozens of photographs of my Sito and Jido horsing around on their front porch after they married in 1948. They lived in a single-floor five-and-a-half (in Montreal speak, a three-bedroom) on Berri St. just north of Jean-Talon. There’s Sito and Jido making out like crazed young lovers. There’s Jido hoisting Sito up in his arms. There’s Jido carrying her up the porch steps like she was feather-light. There’s my mother, just a toddler, posing with Sito on the curved wrought-iron exterior staircase that is so Montréalais.

I stood outside the house, still standing and now occupied by a friendly Vietnamese man who chatted with me and let me tour the interior. And I daydreamed. What I wouldn’t give to go back to that hot June in 1948, when the newly wedded Arabs livened up the Jean-Talon area like smoking embers. What I wouldn’t give to see my young Sito dish it out to Jido.

Stories abound in my family lore of women’s abhorrent treatment at the hands of men; for example, my great-great-aunt Mariam Zakaib was betrothed in utero and married off at twelve. On her wedding night, she wanted to play with her dolls while her adult husband decidedly did not, so he beat her. She ended up having two children by the age of fifteen. This all occurred not in Lebanon, but here in Montreal. Then again, there are many stories of the powerful women in my family taking a stand, such as my Sito, whose father abandoned her and the family when she was four years old. Years later, when she was married, he tried to muscle his way back into her life, and my Sito told him to take a hike. He was never heard from again, and died alone in Drumheller, Alberta. Maybe, as a modern feminist, I wouldn’t be so unrecognizable to my ancestors after all.

Around the corner, I walked back to St. Nick’s and encountered the priest. I’d heard him say that somewhere, buried in the church halls, was a bust of my great-grandfather. Now, he kindly obliged me by searching for it. He dragged a big, dilapidated cardboard box to the middle of the church nave and opened the flaps. There, in gold, was the distinct face of Michael Zarbatany. And lo and behold, upon the bridge of his nose sat his actual, original spectacles. I stared and stared, but unlike the uncanny likeness I bear to my Jido, I couldn’t see a resemblance between him and me. I was a bit disappointed.

As I explained this to the priest, he paused and said, “Wait right here.” He disappeared and then returned holding a black leather-bound book. “This was your great-grandfather’s prayer book,” he said. “It’s all in Arabic, but his notes and handwriting are all up and down the margins. You should take it; it’s just sitting on a shelf collecting dust in the back of the church. Now it’s back in the family.”

For the briefest of moments, I suddenly had my entire family around me, their faces nodding in approval, their arms embracing me. They, and I, were home.

Christine Estima’s essays have appeared in the New York Times, the Walrus, the Globe and Mail, the Toronto Star, New York Daily News, VICE, CBC, etalk, Metro News, Bitch Magazine, and many more outlets. She was a finalist for the 2018 Allan Slaight Prize for Journalism.