Art by Jay White

Art by Jay White

KTAQMKUK

Learning of his Mi’kmaw ancestry came as a surprise to Justin Brake, who always considered himself a Newfoundlander. What might it mean, he asks, to ethically explore the question of his identity?

My parents were just months away from their high school graduation in rural Newfoundland when they welcomed me into the world. Before I came home from the hospital, my grandfather—“Poppy” or “Pop” for most locals—returned from work one day with a baby crib. “Justin’s going to need a place to sleep,” he told my father, who turned eighteen just days before my birth.

When I was a toddler, my time at home came to an abrupt end. With scarce career opportunities on the island, my father was an easy recruit for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, who at the time visited high schools and often enticed students into the force. We were posted to the Toronto region, then rural Saskatchewan, and eventually Ottawa, where I spent the rest of my childhood and adolescence.

We returned to Gander every Christmas or summer, and that’s where we made our most cherished memories. In wintertime, my pop tasked me with hauling frozen rabbit carcasses out of the woods when we’d check the snares on his trapline. In summertime, I trouted with my father, uncles and cousins. We cut young alder branches to tether our fish through the gills until we got home. My grandmother—“Nan”—greeted us with a warm smile each time. Then she would put on her apron, clean the fish in the kitchen sink and fry them up for supper.

Pop was at peace in the woods. I recall watching him cut and split wood for the stove that heated his home, the same small bungalow where my father and his six siblings were raised. As I got older, I helped him load and unload cords of wood. We’d stack it to the ceiling in the basement storage room in preparation for winter.

He was known in Gander as a good neighbour, a friendly businessman, a volunteer and a multi-term town councillor. I used to climb and play among the boxes in the warehouse where he sold furniture and appliances. If he knew a family couldn’t afford a new fridge or stove, he often gave it to them at their word of eventual repayment. His charity, my nan later told me, was a factor in the eventual demise of the family business.

There was another side of my pop that I’ve grappled with most of my life, though. I remember the angry outbursts he occasionally directed at those he loved most. It was familiar behaviour. An only child, I sometimes awoke to the sound of my parents fighting downstairs. I’d get out of bed and make my way to the top of the stairwell. Then, afraid to go down, I would curl up on the top stair and listen until I fell asleep.

Of all my childhood memories of Pop, one in particular stands out. It was the summer of 1989 and I was eight years old. He took me out to fish for trout on Square Pond, where he built the family camp. He told the best stories, and I absorbed every word like a sponge. When his surroundings were calm, so was he. On this overcast day there wasn’t a wisp of wind. The water was still. We were seated in his tin boat, just the two of us. He pointed to the shoreline beneath the wooded cliffs. Then he said that if I kept an eye out I might see “Indians.”

I looked to the shore in amazement. Then I looked back at him. I can still see the smile on his face, clear as day. That was the first and only time I recall my pop saying anything about Indigenous people. He never told me his family was Mi’kmaw, or that he grew up on the same land where our ancestors had long made their home for the bounty of salmon and animals there. None of my other relatives had mentioned this either.

As for me, apart from our short visits home, I never felt settled. At thirteen or fourteen I wrote a letter to my parents, who had divorced a few years earlier, and pleaded with them to send me back to Newfoundland. I would live with my aunt and uncle while I finished high school in Gander, I suggested. The answer was no. Looking back, I’m certain I wouldn’t have endured the separation from them. But I also felt unable to cope with my separation from the island.

I had a map of it on my wall and used to study every nook and cranny of every bay. Even as a child, I somehow knew that the island was such a profound part of me that I could never be whole without it. After graduating college in Ottawa, I worked my first newspaper gig out west. Then, after a quarter-century away, I finally made my way home.

It was around this time, in my mid-twenties, that I recall first hearing references within my immediate and extended family to our Mi’kmaw ancestors.

All of the things our family did, like hunting, fishing and just being in the woods whenever possible, were part of our identity as Newfoundlanders, I thought. After all, my other pop—the son of a settler fisherman from Bonavista Bay—did the same: snared rabbits, fished, built a cabin in the woods. All of it.

I’d previously heard fragments of our family history, but why this sudden revelation? And if my family was once Mi’kmaw, at what point did we stop being Mi’kmaw? Where was the rupture in our family? Do the reasons why this rupture happened matter as I negotiate my identity today?

By the time the stories about our Mi’kmaw heritage started emerging, Pop was bed-bound in a long-term care home. He was blind from his diabetes and increasingly unable to make sense of the world around him once the dementia took hold. When he was lucid, I tried to gently ask him about his early life and where we came from. But, in pure Pop fashion, he responded each time with improvised stories replete with humorous anecdotes and fragments of reality and complete and utter fiction. They were so intertwined that I rarely knew what was real. All I could do was smile and cherish the moments.

During one of my final visits with Pop, I took his hand and told him I knew about the crib he had brought home for me, and that my father still had it stored in his basement.

“Do you remember that?” I asked, gently squeezing his hand.

“Uh huh,” he mumbled.

“I want you to know how much that means to me.”

He squeezed back. A tear ran down his face.

I didn’t know then that the answers I was looking for weren’t buried in Pop’s suppressed memories, needing to be dug up. There were hints before me all along, in Pop’s silence on the matter, and in my own lived experiences.

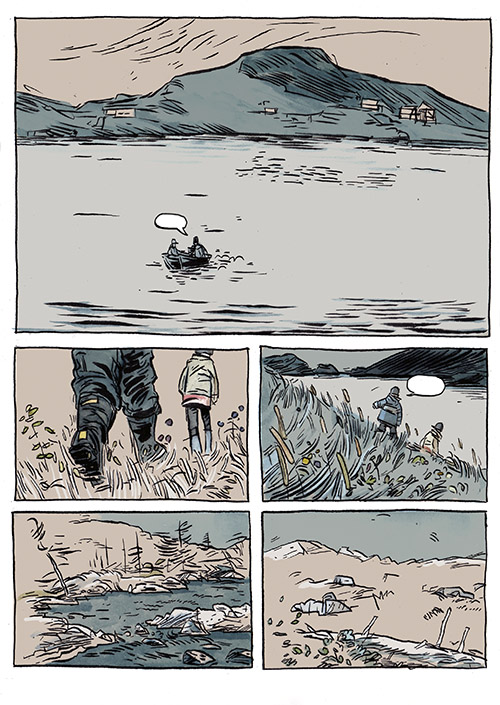

Edward Brake, my pop, was born in 1936 at Riverhead in what’s now Corner Brook. It’s a community of around twenty thousand people and the primary business and service hub of western Newfoundland. Later renamed Humbermouth, Riverhead refers to the place where Maqtukwek—the “Mighty Humber River” as Pop called it—empties into the southernmost arm of the Bay of Islands.

He grew up there, on the same land where my ancestors made their home from the late eighteenth century onward. Surrounded by mountains, the area is beautiful, an estuary once bountiful in Atlantic salmon, trout and other foods. The Brakes were one of the first families, if not the first, to settle in the area and my relatives now number in the thousands. My forebears remained at Riverhead until the early 1960s when my father was born in Gander, the new international airport town in central Newfoundland where my grandparents had moved to raise their family.

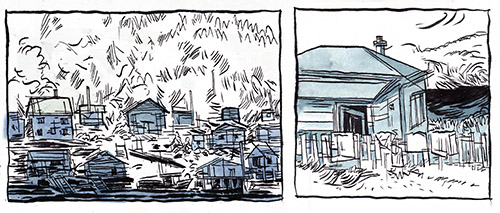

To this day, the spot at Riverhead where my family lived for two and a half centuries still bears the name Brake’s Cove. The late nineteenth century establishment of the Newfoundland Railway and the early twentieth century construction of a pulp and paper mill in Corner Brook brought a flood of settlers to the area. The families who lived at Brake’s Cove were increasingly surrounded by industrial development and eventually forced off their land. Some of my ancestors are buried at Brake’s Cove, in what the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador and the City of Corner Brook recognize as an old cemetery with special protections under provincial and municipal laws.

I was oblivious to my family’s Indigeneity—and to Mi’kmaw history on the island—throughout the first quarter-century of my life. Outside of Miawpukek First Nation (also known as Conne River) on the island’s south coast, I’d only ever heard of the Beothuk and their demise. With time, I’d learn that the island is imbued with a rich archaeological record up to six thousand years old. Historical settler records document a Mi’kmaq presence on the island dating back to the seventeenth century. Oral history in Ktaqmkuk (Newfoundland) says Mi’kmaq have occupied the island since pre-contact times.

Prior to colonization, Mi’kmaq were seasonally nomadic on both land and water. They were seafarers who built vessels and birch bark canoes to access what anthropologist Charles Martijn describes as their “domain of islands” in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, “linked, not separated, by stretches of water, like the Cabot Strait, which served as connecting highways for canoe travel.”

Mi’kmaq had relations and intermarried with Innu, who periodically travelled south to the island from their homeland of Nitassinan. They also allied with the French in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, first in trade, and later for political and military reasons when they fought back against British colonial expansion.

In Ktaqmkuk, Mi’kmaq intermarried with French settlers and lived primarily along the south and southwest coasts, eventually expanding into Beothuk territory as the number of the island’s earlier inhabitants dwindled. Colonial myths once claimed the French brought Mi’kmaq to Newfoundland from Nova Scotia to help kill off the Beothuk. But Mi’kmaq have vehemently denied the allegation and other historians agree. According to oral history, Mi’kmaq in fact intermarried with Beothuk families and sheltered them when settlers began venturing into the island’s interior in the late eighteenth century.

It was around this time that my ancestors built their homestead in the Bay of Islands. Jane Matthews, an “Indian” woman born in Burgeo on the island’s south coast around 1773, married Ralph Brake, a British man sent by the Church to Newfoundland as a boy following the death of his father. Just thirteen when he arrived in Newfoundland, Ralph was apprenticed into the fishing trade. He and Jane provided for their ten children largely thanks to the salmon and trout Ralph netted at Humbermouth. Among their sons was Edward Matthews Brake, my namesake through my paternal lineage when I was named Justin Edward forty years ago. The Brakes, according to historical accounts and to local history, have always been regarded as “Indian” or “Micmac.”

“The Brake families provide an interesting example of how aboriginal and immigrant cultures merged in west coast Newfoundland. Elements of both cultures were retained, but it seems that, in day to day life, the Micmac way of life prevailed,” anthropologist Dorothy Stewart and Mi’kmaw Elder Marlene Companion wrote in a report for the Federation of Newfoundland Indians (FNI).

In 1878, Edward Brake—son of Edward Matthews Brake—married Josephine Duval, a Mi’kmaw woman from Bay St. George, home of the island’s second most populous Mi’kmaw community. Together they raised my great-grandfather William, who, living at Brake’s Cove in 1936 with his wife Sarah Elizabeth (“Lizzie”), brought my grandfather Edward into the world.

William worked as a repairman for the Newfoundland Railway. He and my great-grandmother raised six children at Humbermouth. Then tragedy struck. My great-grandfather fell ill with tuberculosis, a leading cause of death in Newfoundland at the time. He was sent by train to St. John’s where he was admitted to the sanatorium.

One day in July 1943, my pop, just seven at the time, went up the road to the train station to greet his father, who he’d heard was coming home. The passengers disembarked, but there was no sign of William. According to the story told to me by my aunt, my pop asked a railway employee if they had seen Bill Brake aboard the train. “He’s dead,” the man said, looking down at my pop. Pop collapsed to the ground. His father returned home in a casket.

My great-grandmother later remarried. Her new husband was a white man whose name I won’t repeat here. Throughout the remainder of my grandfather’s and his siblings’ childhood and adolescence, their stepfather inflicted unspeakable violence on them. Unspeakable not only because of how horrific the details are—but also because some of his survivors still live today and their story is not mine to tell. I believe my great-grandfather’s death and the subsequent violence marked a significant rupture of my family’s way of life.

The more I learned about what happened at Brake’s Cove in the 1940s and fifties, the more some painful realities in my own life began to make sense. There is intergenerational trauma in my family so profound and complex that even acknowledging it is taboo. Unfortunately, that trauma has also impeded my ability to reconnect with my family’s past.

A friend I once confided in about my experiences summed it all up quite concisely: “Colonialism is a bitch.”

From the late nineteenth century onward, a number of social, political and economic factors contributed to an increasingly hostile environment for Mi’kmaq on the island. “Our problem was not being proud of who we were because being Indian or Micmac had a bad stigma attached to it,” said Miawpukek Elder Marilyn John. “Being a Micmac or Indian back when I was a child meant you were a dirty, greasy Micmac and not something to be proud of. We were made to feel inferior.”

When Newfoundland joined Confederation in 1949, neither the province, nor Canada, recognized the existence of Indigenous people there, including the Innu and Inuit of Labrador. They were omitted from the terms of union, which for Innu and Mi’kmaq meant the federal government—from its own perspective—had no legal responsibility to provide programs or services to them under the Indian Act.

Twenty years later, Pierre Trudeau’s 1969 White Paper proposed dismantling the Indian Act in an attempt to make all people equal citizens under Canadian law. First Nations across the country pushed back hard.

The resistance inspired Indigenous peoples in the province to unite in their fight for recognition and self-determination. They established the Native Association of Newfoundland and Labrador and later split to form their own organizations. The FNI represented six affiliated Mi’kmaq bands on the island—in Benoit’s Cove, Corner Brook, Flat Bay, Gander Bay, Glenwood and Port au Port.

In 1984, the federal government formally recognized the people of Conne River and three years later established the Miawpukek reserve there. Meanwhile, the FNI forged ahead. In 1989, now representing nine Mi’kmaq bands, the organization took legal action against Canada seeking a declaration that their members were eligible for status under the Indian Act.

Exploratory discussions began in 2002 and led Canada and the FNI to an eventual agreement-in-principle ratified and signed by FNI members in 2008. It established a band through which FNI members from communities across western and central Newfoundland would be eligible to apply for enrolment. It would become known as Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation, one of only a few First Nations bands for which Canada has not allocated reserve lands.

The criteria for Qalipu membership required applicants to self-identify, prove ancestry by birth or adoption, be a member (or descendant of one) of a pre-Confederation Newfoundland Mi’kmaw community, and be accepted by a designated Mi’kmaw community.

The band membership criteria established by the FNI and Canada were guided by the 2003 Supreme Court of Canada Powley decision, which recognized that belonging to an Aboriginal group requires at least three elements: Aboriginal ancestry, self-identification, and acceptance by the group. In its decision, the Supreme Court wrote that “self-identification should not be of recent vintage,” and that “[w]hile an individual’s self-identification need not be static or monolithic, claims that are made belatedly in order to benefit from a s. 35 right will not satisfy the self-identification requirement.” (Section 35 of the Canadian constitution entrenches Aboriginal and treaty rights in the country’s supreme law.)

It was during the final years of the FNI and Canada’s negotiations that stories of my family history began surfacing. After Pop passed away, a few relatives managed our family’s application for membership in Qalipu. I uncritically accepted broad justifications I’d heard within my family and from others in Newfoundland: Our identity was suppressed by stigma and racism; some of our ancestors’ ways were passed on to us but not labelled Mi’kmaw; it is our birthright to reclaim our lost identity and apply for Indian status, which would come with some benefits that we deserve in part for all that had been taken from us. The normalization of this rationale throughout the province made everything believable, morally justifiable, and therefore palatable.

At the time of the agreement, the FNI represented 10,500 people. By the initial application deadline for founding membership in the band, the Qalipu enrolment committee had received nearly thirty thousand applications, which were still flooding in from people on the island and from the vast Newfoundland diaspora.

In September 2011, Canada officially made Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation a band under the Indian Act. With nearly twenty-four thousand members, it was one of the most populous bands in Canada. (The FNI was effectively dissolved as a political advocacy organization but continued to serve as the legal entity with which Canada had to deal on issues related to Qalipu’s foundation and band membership. Since Qalipu’s establishment, its chief and council double as FNI’s board of directors.)

But this was just the beginning. The enrolment committee went on to receive another seventy thousand applications, bringing the total number of applicants to just over one hundred thousand—a number that haunts Qalipu and Mi’kmaq of Ktaqmkuk to this day.

The number of applications for Qalipu membership prompted suspicion among Mi’kmaw leaders and others outside the province. The Sante’ Mawiomi (Mi’kmaq Grand Council) appealed to the United Nations, writing in an October 2013 letter that Canada had “wrongly interpreted” the scope of its constitutional responsibilities and was violating the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples by determining Mi’kmaw citizenship—not just “Indian” status—through Qalipu. The Sante’ Mawiomi had not been consulted by the feds or Qalipu, it said.

“This concern is not with all Mi’kmaq from Newfoundland, in fact we have consistently had Keptins representing Newfoundland on the Grand Council for generations. (Keptins, or “Captains,” are community and regional representatives on the Grand Council.) These new Qalipu members we simply do not know and do not recognize as Mi’kmaq,” reads the letter, signed by the late Grand Chief Ben Sylliboy and others.

Pushback from Mi’kmaw leadership outside the province and then-Qalipu Chief Brendan Sheppard’s dismissal of the Sante’ Mawiomi’s concerns contributed to my growing anxiety about my own application. I worried about the legitimacy of the process, and ultimately, about my own culpability in what Mi’kmaw leaders themselves were calling a threat to the Mi’kmaw Nation’s sovereignty.

Along with other members of my family, I received my Qalipu letter of acceptance in 2011 and was officially a “registered Indian” under the Indian Act. But the questions had already started piling up, and my deep unease with suddenly identifying as a First Nations person was eating away at me. I never filled out the forms for my status card and never used my status for “benefits.” Surely, there had to be more to an identity shift of this magnitude beyond simply acquiring new information and getting Canada’s stamp of approval.

If I ever identify as L’nu, it should be without pressure from Canada or anyone else, I thought to myself. I felt Qalipu’s creation without the involvement of the rest of the Mi’kmaw Nation, its application deadlines, and the colonialist membership criteria represented a questionable way to right past historical wrongs.

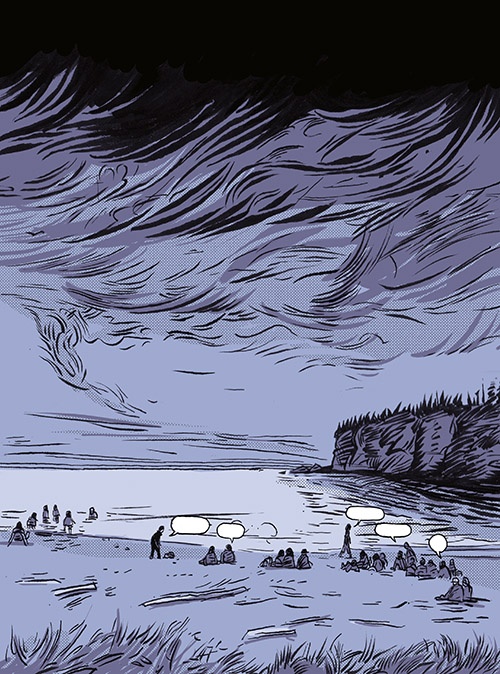

So I began searching for answers elsewhere. I attended powwows in Miawpukek and No’kmaq Village at Flat Bay, where I met Elders and other traditional people who graciously shared knowledge of Mi’kmaw history and culture and welcomed me into ceremony and prayer. I introduced myself as a Brake from Humbermouth who grew up away, but never knew of my Mi’kmaw heritage. Everyone knew exactly what family I was from.

In 2016, my partner and I moved to the Bay of Islands, where we bought our first home in Benoit’s Cove, a small fishing village and one of the former FNI communities. Our home looks out over the water and southeast toward Corner Brook. When we married a few months later, we had our wedding photos taken at Humbermouth.

In 2017, we welcomed our daughter Willa into the world. When she was five weeks old, we brought her to the Bay St. George Powwow at No’kmaq Village, where a distant cousin introduced me to another distant cousin, who gifted Willa the tiniest pair of moccasins I’d ever seen.

A sense of belonging began to form inside of me. No one questioned whether I was “legitimate.” Most didn’t care at all about Qalipu membership or Indian status. But I still carried reservations and uncertainty everywhere I went.

The Joseph Boyden scandal in 2016 ignited an unprecedented public discussion around Indigenous identity and belonging. More recently, filmmaker Michelle Latimer’s claimed connection to the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg community in Quebec has been refuted, her critics pointing out that Latimer’s Algonquin Métis identity claims are based on ancestors from the 1600s.

In 2011, University of Texas anthropologist Circe Sturm coined the term “race shifting” while shedding light on the exponential growth of self-identified Cherokee in the US between 1970 and 2000. Despite their diverse backgrounds and circumstances, she wrote, these individuals “share a firm belief that they have Indian blood and that this means something significant about who they are and how they should live their lives.”

A similar movement has taken shape in Eastern Canada, where over the past two decades, thousands of people with Acadian and French settler ancestry began self-identifying as “métis.” They have developed political advocacy organizations and some have issued their own fake status cards, committed tax fraud, and have openly expressed anti-Indigenous racism. The groups hold a common belief rooted in colonialist race-based logic that having an Indigenous ancestor or having “Indian blood” is a paramount factor of Indigeneity. Métis and Mi’kmaw leaders have called the movement a threat to both Nations’ self-determination, as many of the groups have formed in Mi’kma’ki.

For their part, many Métis have countered the idea of racial mixedness as a defining factor of Métis identity. They point out that Métis nationhood emerged from specific historical circumstances, including particular kinship relations, land-based economies and other unique social, cultural and political factors.

The term Métis “must first be understood not as part of a discourse of hybridity but instead through its connection to a ‘national core’ historically located in Red River and in the shared memories of the territory, leaders, events, and culture that sustain the Métis people today,” writes Métis scholar Chris Andersen.

Métisness “is more than who you are related to,” Jennifer Adese, a Métis sociologist at the University of Toronto, said in 2017. “Kinship and in particular our concept of wahkohtowin is an active process of relationship that speaks not just to flat points of connection but to an active process of responsibility and reciprocity.”

Similarly, Mi’kmaw lawyer, activist and scholar Pamela Palmater and others have challenged the colonial imposition of blood quantum and race-based definitions of identity on First Nations peoples via the Indian Act, saying it’s not only reductionist and discriminatory, but genocidal.

“One of the most effective ways of accomplishing the legal elimination of Indians has been through the federal determination of who is and who is not an Indian,” Palmater wrote in 2014. “Canada’s ultimate priority with regards to Indian registration remains their legislative extinction over time and the perceived associated financial gains that attach to reduced numbers of Indians.”

Darryl Leroux, a researcher at St. Mary’s University in Halifax who has done extensive work on race shifting among so-called “Eastern métis” in Quebec and the Maritimes, says that in their effort to self-indigenize, white settlers “do” descent by locating distant ancestors—sometimes Indigenous, sometimes not—as a way to claim an Indigenous identity today.

“These practices of descent are a form of legitimization—through their self-recognition, race shifters claim a legitimacy to speak for and act as Indigenous peoples,” Leroux writes in his 2019 book on the subject. “Race shifters solidify colonial logics through transcending colonialism altogether, thereby evading responsibility in more than three centuries of colonial violence by retroactively claiming indigeneity.”

Leroux’s work deals with Indigenous ancestry and identity, but it “tells us much more about the shifting politics of whiteness, white privilege, and white supremacy,” he writes. Palmater has said the appropriation of Indigenous identity represents a “new wave of colonization.”

There are Mi’kmaw people in Newfoundland, and thousands more who are doing the hard work of building relations and community, learning the Mi’kmaw language, and creating beautiful expressions of identity and belonging—all as part of a cultural reclamation.

But there has also been a profound lack of awareness of the whiteness and white privilege many of us carry. It informs how we understand ourselves and others, how we think about the world, and crucially, how we develop our identities.

While race shifters “would prefer to keep the specter of whiteness under wraps, it still manages to emerge in their narratives in a variety of ways,” writes Sturm, “particularly in the language of choice that they use to describe their racial becoming—without realizing that choice itself is a subtle marker of whiteness.”

I was accepted into Qalipu based on proven ancestry, self-identification—uninformed and reluctant as it was—and acceptance by the group. Outside of the ancestry requirement, proving the other criteria rested upon sworn affidavits by family members in Gander.

My privilege as a white cis man and the opportunities I’ve had stand in stark contrast to the lived realities of most Mi’kmaq today. For many like me, the creation of Qalipu led to a quick education in—or reinterpretation of—our family histories in order to meet membership deadlines. Missing from the process was any meaningful public dialogue around the implications of our collective actions.

Meanwhile, many of those whom we claimed to be in kinship or community with have always identified as Mi’kmaw, have always lived on the margins of society, and consider Qalipu membership and Indian status an affirmation of their long-denied truth. These are two distinct sets of circumstances.

Once we acknowledge this, we can no longer deny that with privilege comes responsibility. During Qalipu’s formative years there has been very little public discussion about responsibility, with a glaring exception—one of the few remaining people who started it all.

“We got lost because people lost sight of the objective,” Mi’kmaw Elder and former Flat Bay Chief Calvin White told a small audience in Woody Point, a town on the island’s west coast, in 2017. Above White, Mi’kmaw symbols and hieroglyphics decorated the ceiling of St. Patrick’s Church, which was built in 1875 and later restored as a concert hall.

White was one of the founders of the movement for Mi’kmaw recognition in Newfoundland and Labrador a half century ago, and later travelled across Canada as a member of the National Indian Brotherhood to build solidarity among First Nations. He said the movement was intended to force Canada to recognize the Mi’kmaq of Newfoundland so they could begin rebuilding a culture of “sharing and caring” that had been destroyed by colonialism and left many living in poverty. “The damage that is happening right now will be cemented, and there’s going to be no opportunity for change,” he said, speaking about the latest developments with Qalipu.

In July 2013, the federal government, with the consent of the FNI, legislated a review of all Qalipu applications, with the exception of those which had already been processed and rejected. Applicants were invited to submit further documentation supporting their claim in order to meet the membership criteria. This time— for anyone living more than twenty kilometres outside of a designated community—the enrolment committee would assess applications using a point system. To be accepted, applicants needed a minimum of thirteen points allocated through a number of categories loosely related to the original Powley-based criteria.

Six points were up for grabs if an individual could prove frequent visits to and communication with family members in a designated Newfoundland community. In turn, people submitted old plane tickets, phone bills and Walmart receipts. Living on the island garnered three points, while proving membership in a Mi’kmaw organization prior to the establishment of Qalipu was worth nine. Finally, evidence of the “maintenance of Mi’kmaq culture and way of life through knowledge of Mi’kmaq culture and participation in cultural, religious, ceremony and traditional activities” could earn an applicant nine points.

In Canada’s effort to reduce the number of eligible Qalipu applicants, it had effectively mathematized Mi’kmaw identity. Thousands were forced into a high-stakes game of achieving imposed goals by arbitrary deadlines in order to prove they are who they say they are. For those with limited access to education and health care, winning or losing this game may be a matter of life or death.

The process eroded any remaining faith I had in a just outcome, and I considered my continued participation an act of self-interest. Placing my own interests ahead of those being disenfranchised by the process contradicted what I had learned about Mi’kmaw values and principles. Instead, I used my platform as a journalist to report on the ongoing fiasco. The February 2014 deadline came and went, and I chose not to submit any further documentation to make my case for continued membership.

In 2017, the federal government revoked more than ten thousand Qalipu members’ Indian status. Families and communities were divided, lawsuits against Canada and the FNI were launched, and many who’ve always identified and lived as L’nu’k were excluded.

“The most vulnerable people are the ones that are least likely to be able to step over those thresholds and probably are the most Mi’kmaw, if we’re going to talk about degrees of being Indigenous,” my friend Kelly Butler, a Mi’kmaw woman whose family is from Bay St. George and who is an Indigenous education specialist at Memorial University, told me in 2017. “[They are] people who are still living on the land, people who are of advanced age, and people who stayed in those rural areas, and didn’t move to urban areas, [or who] have a lower level of formal education.”

White called the Qalipu enrolment process a “joke” and the entire situation a “crisis” in 2017, explaining the FNI and Canada were “leaving behind” many of the very people the movement and the FNI were founded to help. The point system was a far stretch from the fourth generation citizenship code that White and others had proposed for Flat Bay two decades ago, which the Elder says would have included everyone within the community’s collective memory. Based largely on where they lived in their adult lives, under the Qalipu criteria, three of White’s children were denied membership while three were accepted. In my own family, most, but not all, retained their status.

The point system “reduces everyone to an individual level and forces you as an individual to come up with points,” says Butler. “To me that is part of the federal project to assimilate everybody, is to separate us all out and make us all individuals and to only care about ourselves.”

With Newfoundland’s status as a British colony and dominion before it joined Canada, Mi’kmaq experienced colonization differently than in the other parts of Mi’kma’ki, which were subjected to the Indian Act. Mi’kmaq were among the first in what would later be called Canada to face the violence and dispossession of European colonization.

“So we lost the most the fastest in terms of cultural identity,” says Miawpukek Chief Mi’sel Joe, who has been a central figure in the Mi’kmaw fight for recognition and self-determination since the 1970s. Consequently, he says, “we no longer have Mi’kmaw law, we no longer have Mi’kmaw anything—what we have is little bits and pieces that we’re working with.”

Joe is Newfoundland’s only current representative on the Sante’ Mawiomi. In 2019, he accompanied Mi’kmaq Grand Chief Norman Sylliboy, Grand Keptin Antle Denny and Keptin Stephen Augustine in their first delegation visit to Mi’kmaw territory in western Newfoundland, at the invitation of Qalipu. “We were happy to visit and meet some of our relations, visit communities and acknowledge our extended Mi’kmaq family. Unity is the Mi’kmaq way,” Denny said at the time, according to a Qalipu press release.

Meanwhile, the community’s inner turmoil continues. While an unknown number of people who may not meet the Supreme Court’s definition of an Aboriginal person now hold membership in the band, many former FNI members and others who have long identified as Mi’kmaw remain excluded.

As a band councillor and FNI board member in 2013, Qalipu Chief Brendan Mitchell voted in favour of the point system. But he’s since spent much of his time as chief fighting the federal government to have the former FNI members’ status reinstated. (Mitchell declined to be interviewed for this story.)

Even if that happens, Qalipu membership criteria remain based on colonialist ideas of identity and belonging. Joe says it may be time for Newfoundland to develop its own Mi’kmaw citizenship code. “I think we have an obligation to do that,” he says, noting that at the community level Miawpukuk already recognizes some non-status people as citizens.

In 2017, after seven years as a member of Qalipu, I received a letter from the enrolment committee saying I was out. As intended, I didn’t earn enough points to meet Canada’s definition of a Mi’kmaw person.

Months later, my family and I left the island to pursue work opportunities. Although I hadn’t yet made sense of everything, it felt important to remain on the island and in community with others. It pained me to leave at precisely the time when I had begun to find my path, and when I was on the cusp of affording my daughter the experience of living in the territory of her ancestors. After living off the island for more than three years now, we hope to return home someday.

When Latimer broke her five-month silence in a May interview with the Globe and Mail, she doubled down on her identity claims and said “all I can do is speak my truth.” She is now suing the CBC and Indigenous journalists who have reported on her story, alleging in her statement of claim an invasion of privacy and that “she was entitled to a measure of solitude as to the precise outline of her indigeneity.”

The public backlash to Latimer’s conduct has been swift. The validity of her ancestral claims aside, for many, the formerly celebrated filmmaker now represents what not to do when trying to establish connections with a community. There’s also a more subtle lesson in Latimer’s and others’ efforts to substantiate a claimed Indigenous identity.

Kim TallBear, a professor in the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Native Studies, says the concept of identity itself is colonialist because it promotes individualism over collective well-being. “It is anti-relational when we talk about identity. And this is what settlers want you to do—the settler state wants you to think in terms of individual self-actualization, identity, property and rights.” Relationality, on the other hand, “is not about any of those things,” she says. “This is why I encourage people to think more in terms of who are you trying to relate to?”

“You need these sets of relations to constitute a People,” she explains. “You don’t constitute a People simply out of individuals claiming to have an ancestor, you know, nineteen, fifteen, three, or even two generations ago. That’s not a People. That’s just ancestry.”

I haven’t met anyone else who deliberately relinquished their Indian status. It’s a lonely space in between contradictory narratives that push and pull you toward static identities. But then I was introduced to David Shorter, whose words have provided me some comfort.

“[T]hose who just don’t know if they are Indians, or do not have a group of people claiming them as members of their collective identity, may I suggest that you simply say it: ‘I’m not Indian,’” the University of California, Los Angeles professor—who has Indigenous ancestry but is not Indigenous—wrote in 2015. “It’s okay. We’re not so horrible that we can’t also do really great work at the same time as being afflicted with this condition of being non-Indian.”

It’s a relief to hear someone finally say that it’s “okay” to identify as a settler with Indigenous ancestry. “Just because you could claim something doesn’t mean you should claim something,” Shorter tells me. “If you’re intelligent enough to understand the context of colonialism and how it benefits non-Natives who claim Native identity—or people who have partial or minuscule Native identity—in relationship to people living in active relation with Native communities, then you wouldn’t claim it. You would know that you’re just a few degrees of separation from an active colonization such as erasure.”

TallBear, a citizen of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate in South Dakota, says thinking about building healthy relations instead of solidifying an identity is a more ethical approach for those trying to make sense of their Indigenous ancestry. “We can all be a good relative whether we’re a biological relative or not,” she explains. “And if that’s the object of one’s focus—I’m going to be a good relative to these people, this territory, to my ancestors—I feel like one can’t go wrong when one focuses on that, and when one is careful about the claims that one makes.”

In Newfoundland, as in many places, stories of racism, shame and erasure abound. It’s a common narrative that has led many to conclude their assimilation or their ancestors’ assimilation was not their fault. “It’s true, our ancestors made decisions that we now have to live with—that’s just a fact of the matter,” says TallBear. “And they may not have made those decisions completely by their own choice. There were probably elements of coercion in there. Nonetheless, we live with the ramifications of their decisions.”

The idea is appealing—that I could right the historical wrongs done to my ancestors by claiming their identity and by joining with others in the Ktaqmkuk cultural revival. But positioning myself as a victim of colonization intent on “reclaiming” something that was “taken from me” feels impermissible given my privilege. So I inevitably wonder, for whom and at what point does reclamation become appropriation? Assimilation is real, I think, and cannot be so easily undone.

Shorter and TallBear say these kinds of conversations are necessary, but that they may also provide intellectual ammunition for race shifters intent on self-Indigenizing. For years I’ve wondered why I’ve been drawn more to my Mi’kmaw heritage than to my English, French or Irish heritage. Do I have a deep subconscious desire to be accepted as Indigenous in order to alleviate the white settler guilt of living on stolen land while, in my whiteness, benefitting from historical and ongoing genocide?

Like most who have a sensible understanding of our country’s colonial history, I feel that guilt. And though I’ve learned to channel it into more productive things, I wonder if there’s still a part of me that thinks having some tangible connection to my Mi’kmaw ancestors can somehow put me “on the right side of history.” Someone I recently shared my story with said it best: “The insidiously absorptive nature of colonialism infects even the well-intentioned.”

TallBear says that those who learn they have Indigenous ancestors can’t just erase who they have already become in favour of a new identity. “Our formative years matter,” she says. At the same time, “becoming is ongoing. But becoming is not the same as some essential ‘I am.’ Becoming takes work, and it takes lived affiliation.”

White says if a person learns they have Mi’kmaw ancestry from Newfoundland, they have an individual responsibility. “Ask yourself the question, who am I? Who do you choose to be? And, where am I? Where am I going? And what is my intent?” he says. “Am I doing it because all of a sudden I’ve discovered something that I’m proud of, that I want to be more knowledgeable about, that I want to be able to identify with, that I want to be able to support? Or, am I looking for opportunities?”

So am I Mi’kmaw? There will come a time when I have to answer that question—and it is a judgment call at some point, TallBear says. “There’s going to be a grey area in there, and there’s going to be a line on one side of that where you can probably self-confidently say, no, we’re not [Mi’kmaw], but we’re related to them. And then there’s going to be a line on the other side of that where you can pretty self-confidently say, we are.”

Back home, I would park my car at Brake’s Cove and just stare at the mountains that sheltered my ancestors and, down below, the strong current of the Humber River emptying into the bay. After more than a decade of trying to figure out if and when my family stopped being Mi’kmaw—and if so, if it’s something I can reclaim—my thoughts are in a constant state of flux, like the river. Yet my deep desire for certainty in my identity and where I belong is unmovable, like the mountains.

But so is my desire for justice. L’nu or not, Mi’kmaq are embroiled in a centuries-long fight for survival and to defend their sovereignty. “Whatever you and your children decide on as ‘identity’ you can still work in the service of being good relations and good kin,” says TallBear. “And I think if one always focuses on that then you’re probably making decisions that in the future will be better for your descendants.”

While I may live my whole life pondering my identity, she continues, “that’s not really the most important project, is it? The most important project is being a good relative to Mi’kmaw people who are alive, to people in the past, to people in the future.”

So, to my relatives and those who are doing the hard work of living by the teachings you are learning, fighting for those who are discriminated against, and protecting the lands, waters, air and animals for those who will follow: I see you, cherish you and extend my unconditional love. I will stand by your side as a relative and an ally.

When I set out to write this, I wanted so badly to find my truth and put it down in words. But in the process, I learned something more important: My truth is not my own.

Justin Brake is an independent journalist from Elmastukwek, Ktaqmkuk (Bay of Islands, Newfoundland) who currently lives and works on unceded Algonquin territory in Ottawa. A settler with Mi’kmaw ancestry, he centres his work on Indigenous rights and liberation, social justice, climate action and decolonization.