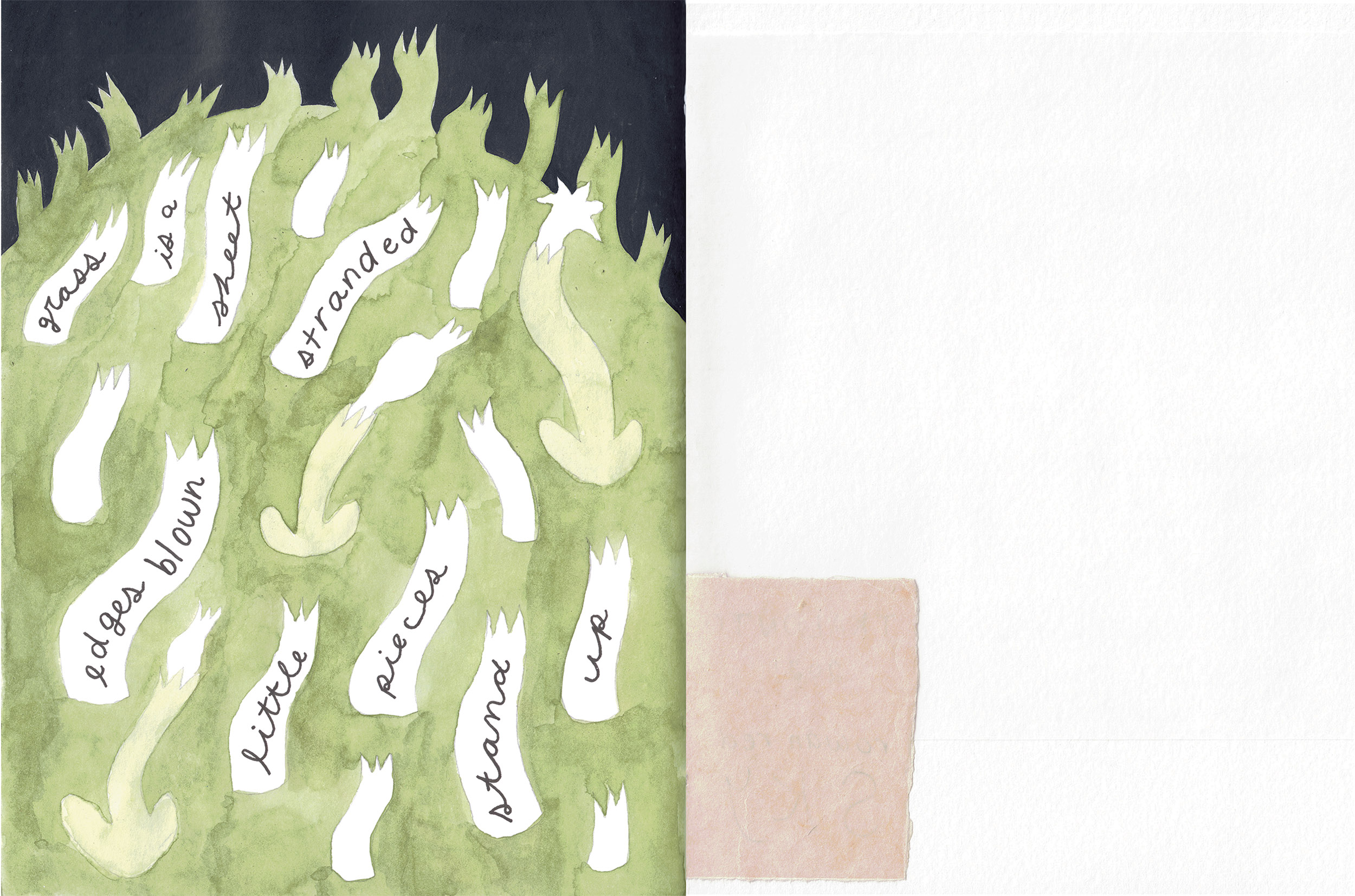

Art by Rowan Red Sky

Art by Rowan Red Sky

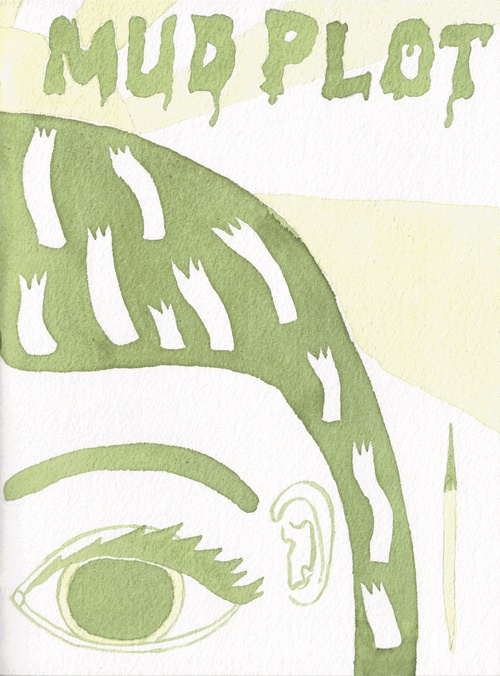

Mud Plot

Trees have a person-like presence in my Indigenous belief system, which is built on Haudenosaunee traditions and collaborative urban Indigenous community practice. Indigenous folks call Toronto, where I live, “The Meeting Place.” People from many different cultures come together here to share ceremony, songs and the teachings of everyday life. Trees live among us as conscious beings, capable of communication and mutual cooperation with the landscape and other creatures. They make community with human and other-than-human beings. Living in downtown Toronto is not living in a forest, but the city has its own ecology.

Trees have a long history of mapping and storytelling. Traditional Anishinaabe songs, ceremonies and stories are recorded on birch bark scrolls. The scrolls have been interpreted and recreated over generations, much like how medieval European manuscripts have been copied by hand to pass down knowledge over centuries. In Haudenosaunee tradition, the eastern white pine is a potent cultural symbol. Historically, pictures of white pine were woven into wampum belts to represent peace agreements between nations, and today the image still symbolizes the unity of the contemporary Haudenosaunee community.

In the late nineteenth century, Mohawk-Canadian poet E. Pauline Johnson inscribed a poem on a strip of birch bark and gave it to Peggy Webling, a British actress and playwright visiting from England. Some historians believe Pauline wrote the poem “To Peggy” with romantic intent. Pauline calls Peggy “An English rose” ... “From lands where roses are.” She describes her own lands as “These where the birch tree flings / His ragged coat / These where the wild pine sings / With dreamful note -”. The words are erotically suggestive; in Victorian traditions, the rose is a symbol of romantic love, and Haudenosaunee oral traditions add layers of meaning to the message.

More recently, Métis/German/Syrian artist Julie Nagam has used birch bark to map memories and reveal hidden Indigenous geographies. She uses a combination of old and new technologies and land-based knowledge, titling her artwork with coded phrases like where white pines lay over the water. In Haudenosaunee tradition, the phrase suggests a place where you go to release your grief. Nagam used a sewing machine on birch bark to map the area where the salmon run up the Niwa’ah Onega’gaih’ih (Humber River) every summer. The “Little Thundering Waters” is one of two major rivers on either side of Toronto. I’m familiar with this spot, too. We don’t know each other, but this shared place connects us. Nagam’s work is about home, migrations and reclaiming the land.

I was considering these thoughts on birch bark, tree traditions, maps and technology while strolling through my neighbourhood this past January. I wanted to explore Indigenous birch bark for myself, but birch is not a readily available material in my downtown neighbourhood. My options were: buy it online and ship it to Toronto, strip a very small and underaged ornamental tree in someone’s front yard, or consider how I could work with different trees that are more readily available in my urban environment.

Under and between expanses of loop-de-looping freeways and train tracks, I found a patch of low-growing buckthorn trees. Dark purple berries still clung to the branches. Berries had dropped and been squished into the pavement beneath the trees to reveal a rich green colour in their juices. This tree is a colonizer from Europe, labelled invasive and often fated for destruction and removal. Under these motorways, most people don’t notice them.

I read some books about medieval European manuscript painting and learned that buckthorn berries can be made into a vibrant olive-green ink called “sap green.” I made up my own easy recipe for buckthorn berry ink after reading several medieval recipes:

Take a palmful of dark purple buckthorn berries, harvested ripe in the autumn or winter.

Boil the berries in one cup of water for a few minutes and strain.

Dissolve a teaspoon of alum (a preservative and colour enhancer) into the ink.

Keep in a glass jar, refrigerate.

By adopting this European practice, I am Indigenizing my relationship with my home environment. Although the tree material I’m using originally came from Europe in the late 1800s, it’s possible for me to relate to the tree in a way that honours my Indigenous ancestral traditions and what I’ve learned from my urban Indigenous community. In time, the tree will likely be removed. For now, I accept that the tree is here, and I work with it to assert my Indigenous values in my colonized environment.

Harvesting the berries doesn’t directly harm the tree, but will slow the dispersion of the invasive species’ seeds into the surrounding bush. Working with other parts of the plant can be passively beneficial to the tree, as well. Skillfully removing bark calls for pruning off damaged and diseased low-lying branches. This improves their health, despite their “invasive” status in North America. The harvested bark can be boiled into a reddish-orange dye. My ink-making practice becomes a reciprocal relationship with the tree in our shared environment.

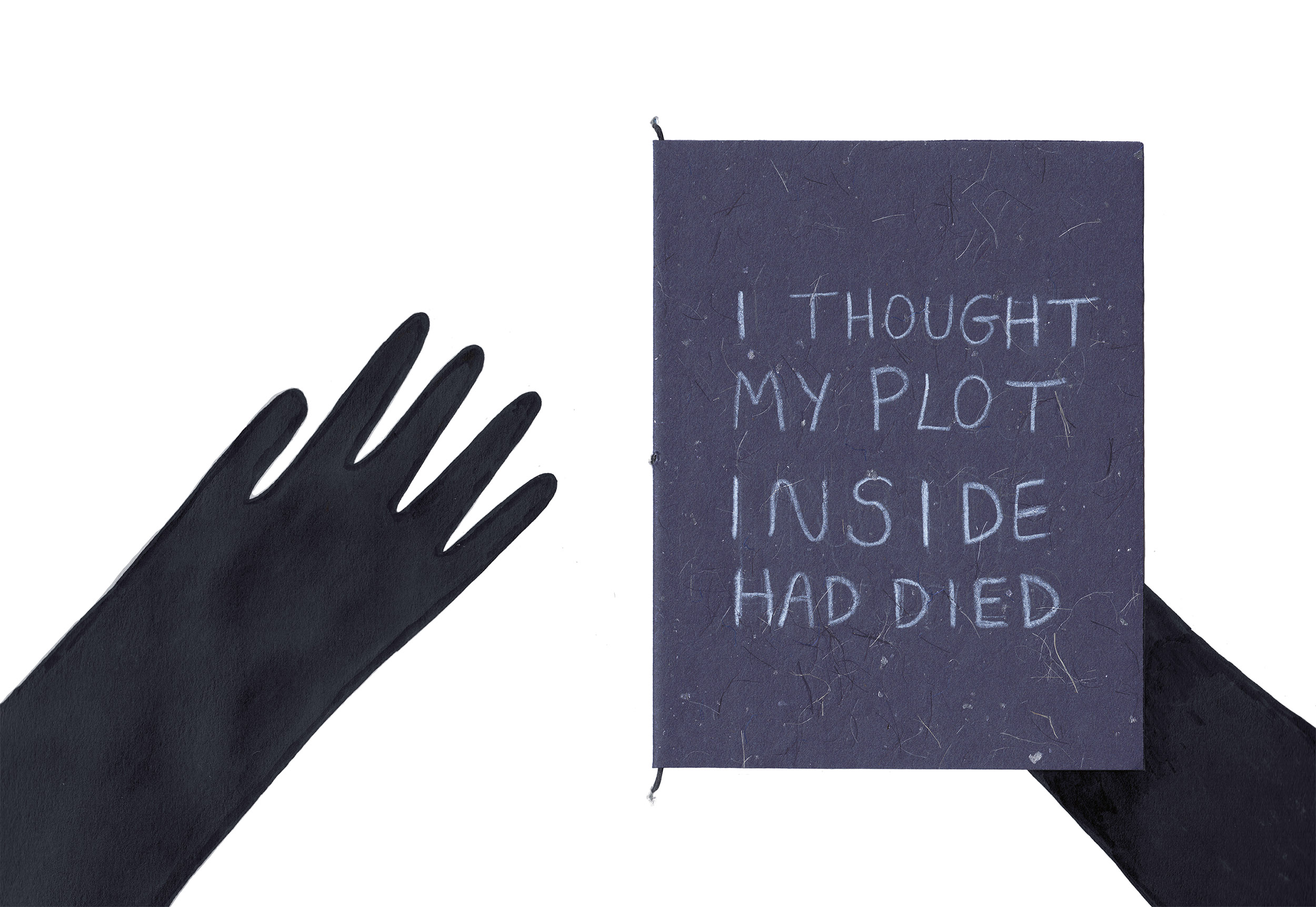

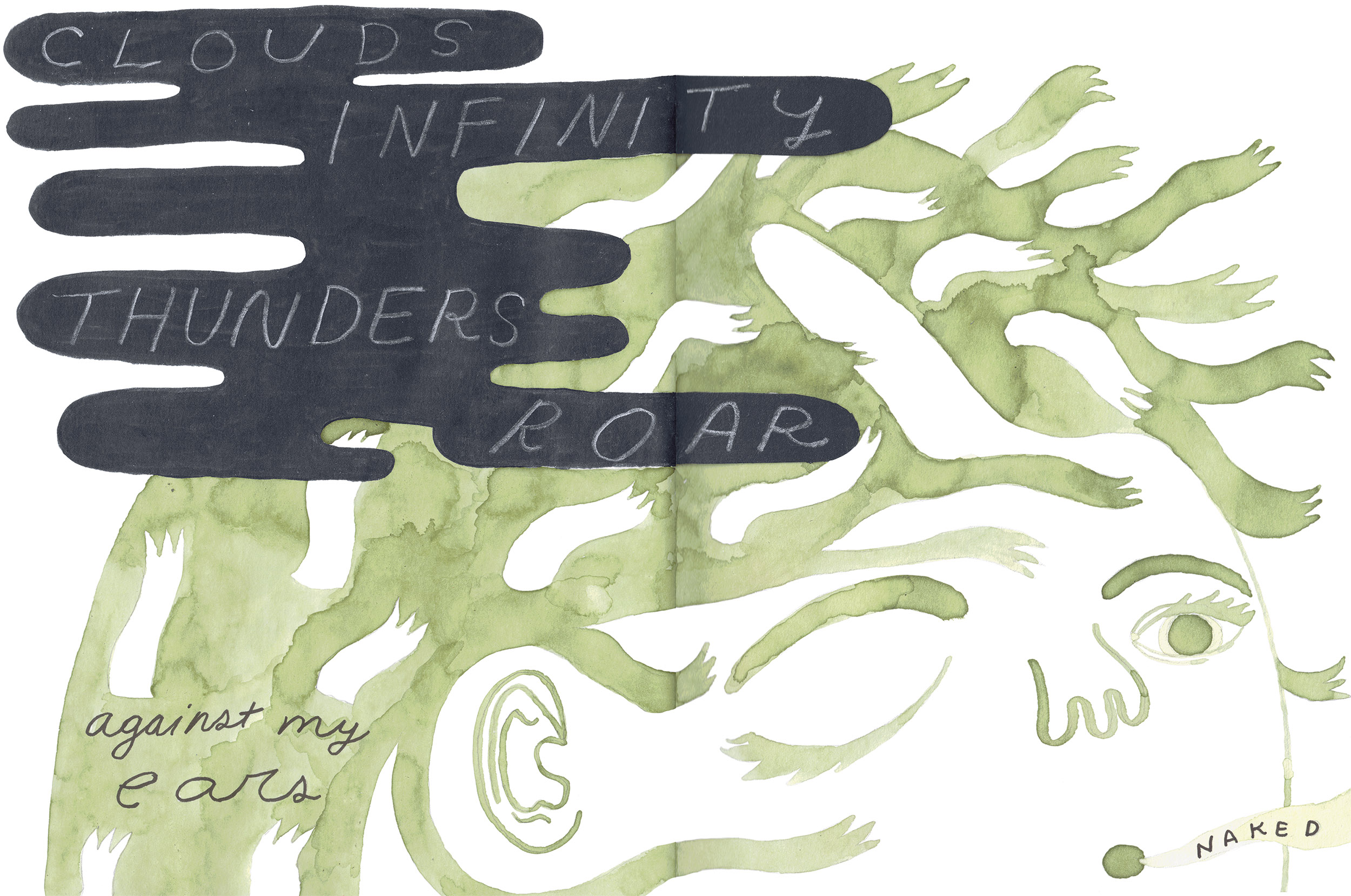

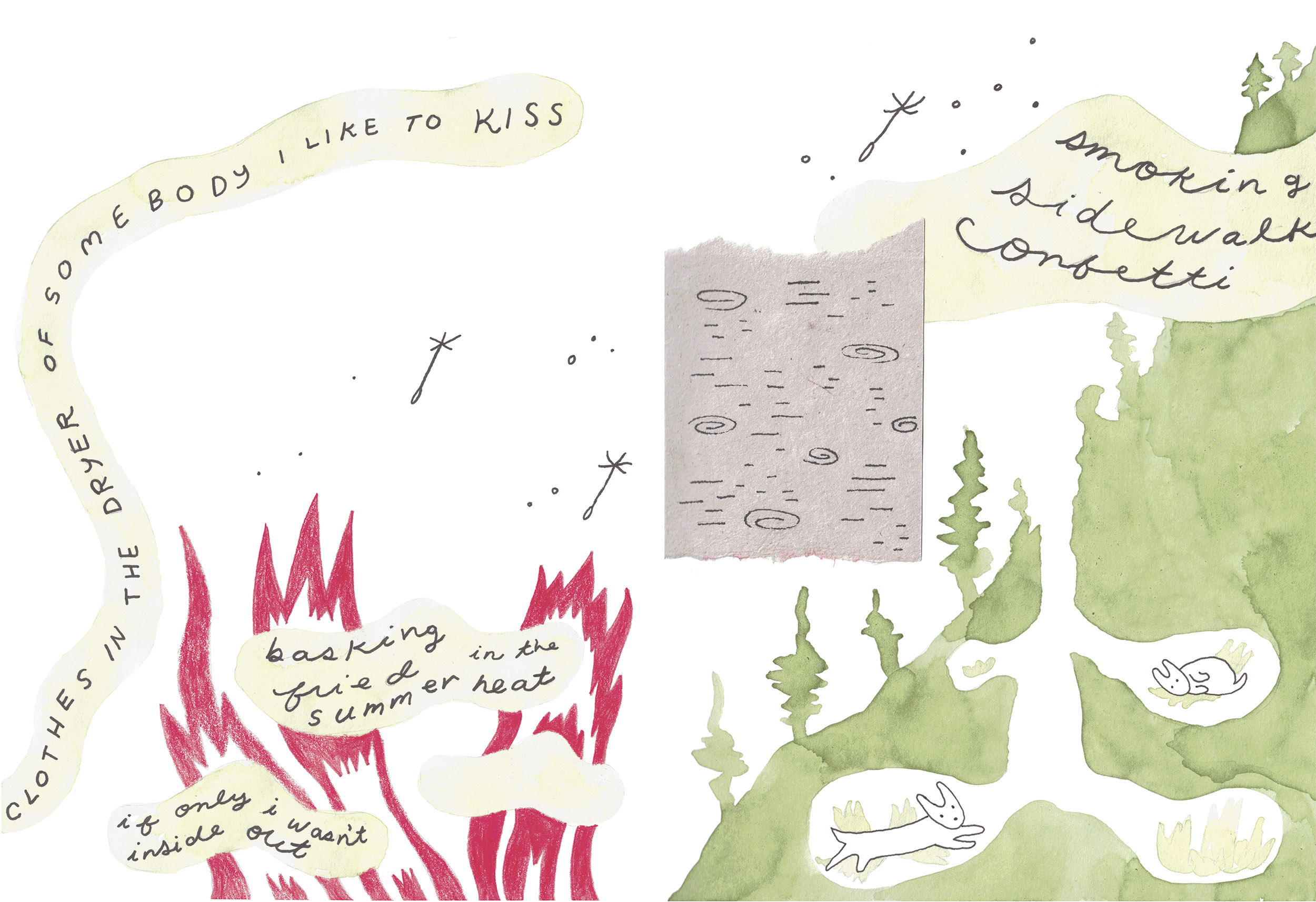

The properties of the liquid ink are delightfully transformative. In the jar, it is an opaque, grey-black colour. On paper, the grey dries into a transparent, vibrant olive green. Using my new homemade sap green ink, I combined poetry, illustration and book design to create an adventurous exploration through imagined forests and meadows full of stories inspired by Haudenosaunee oral tradition.

The land is pictured as a woman, whose hair is the grassy meadows and rugged mountain forests, reflecting the Haudenosaunee story of the Earth Mother. The words and images throughout the book describe the relationships between beings that came together to make the Earth—animal and plant, mud and water, fire and smoke. When I draw with homemade ink, my story becomes part of my neighbourhood ecosystem and the wider tradition of Haudenosaunee storytelling.

Rowan Red Sky is a graduate student studying art history at the University of Toronto. They paint murals and make illustrations that draw from their Indigenous culture to express ideas about land, gender and well-being. Maps, the animacy of the land and the performance of stories inspire their work.