The School in Sakitawak

For survivors of a Saskatchewan residential school, healing can’t begin until the harms are fully acknowledged.

In the fall of 2013, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission held one of its final witnessing events at the Pacific National Exhibition grounds in Vancouver. The day was warm, with some of the last sun shining through the clouds before the autumn rains began. I was standing at a bus stop at the intersection of Renfrew and Hastings, deeper into East Vancouver than I had ever really travelled before. My phone rang and my kokum was on the other end.

“Hi babe,” she said, the same way she’s greeted me since I was a little girl. “Grandma wants you to find her some answers today. You go ask someone why the students at Île-à-la-Crosse weren’t invited into the settlement. We went to residential school, too.” Her voice was strong and indignant. There were many years of hurt bubbling beneath the surface. “You go get grandma some answers. Love you, babe.” She hung up.

Though it happened nearly a decade ago, this phone call still hangs heavy in my heart. It echoes through my body and reminds me of all of the unhealed wounds in my family. This spring, nêhiyaw writer Emily Riddle tweeted: “people asking for residential school booklists don’t realize that all our literature is in some way about residential schools even if not explicitly so.” The intergenerational impacts of the Indian Residential School system scream through our generations and make themselves known in everything we do. My kokum’s wish for me to find her answers doesn’t lead me to a single destination, but represents a lifelong journey.

If I could, I would open my body wide and let it swallow the earth. If I could, I would reach back in time to hold my kokum’s hand as a little girl on the shores of Sakitawak, where she began. If, in the gaping wound of my body holding all time and earth, I could stop the grief before it starts, I would. Nêhiyaw poet Billy-Ray Belcourt writes: “An entire citizenry is implicated. I have just one question left: how does it feel to live in an asylum you built bone by sooty bone? How permanent you made us! Your asylum, outside redemption, outside atonement—I bet it is cold there.”

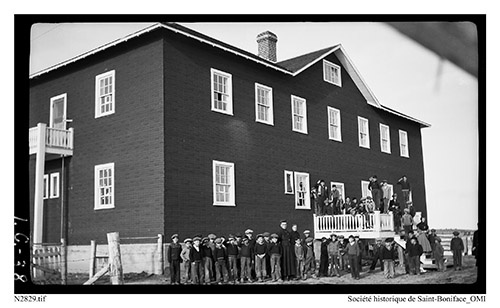

The first iteration of the Île-à-la-Crosse school opened in 1847. To borrow Belcourt’s words, how permanent you made us.

Located about 500 kilometres north of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Île-à-la-Crosse is a small village nestled in an expansion of the Churchill River. Île-à-la-Crosse is also called Sakitawak, a nêhiyawêwin word meaning “where the rivers meet.” In 1776, a trading company based in Montreal established a trade post in Sakitawak. The Hudson’s Bay Company set up a more permanent post in 1799.

The early implementations of trade posts make Île-à-la-Crosse one of the oldest communities in Saskatchewan and a key point in Métis history of the Northwest. This is also one of the origin points of me. My kokum is a Morin. Her dad was a Morin, her mother was a Bouvier, her maternal grandmother a Gardiner. For generations going back, my family has come from Île-à-la-Crosse, where my kokum was born.

In 1846, two Oblates named Alexandre-Antonin Taché and Louis François Laflèche established a mission at Sakitawak and soon after, built the first school. They were sent there by Bishop Joseph-Norbert Provencher, who was tasked with spreading Catholicism throughout the Northwest of Canada through education, conversion and settlement by Catholic settlers. Unlike the residential and day schools set up by the federal government and administered by the church, the school at Île-à-la-Crosse was funded by the church and, later, the province. It hardly received any federal funding in its long history.

The experiences of Métis students in the Indian Residential School system were complex and held in a legislative quagmire. Though not governed through the Indian Act, the Indian Act affects the ways in which the federal government dictates its relationship with Métis—legally classified as halfbreeds—and non-status First Nations peoples. The halfbreeds, my people, were considered “dangerous” by the Canadian state and, as such, were seen as entities who needed to be civilized and assimilated.

This racist need to assimilate Métis children was met with a federal versus provincial stalemate: neither government wanted to cover the cost of educating Métis students, but both governments wanted the Nation suppressed. As a result, some Métis attended federally funded residential schools, while others went to provincially funded schools or mission schools like the one in Île-à-la-Crosse.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission tells us that “The Métis experience is an important reminder that the impact of residential schools extends beyond the formal residential school program that Indian Affairs operated. The history of these provincial schools and the experiences of Métis students in these schools remains to be written.” Regardless of whether it was a federal school, a provincial school, or a church-run school, the end game was the same: civilize and assimilate. It just came down to who wanted to pay the bill.

Canadian nation-building has never been a friendly project for Indigenous peoples. In The North-West is Our Mother, Métis historian and lawyer Jean Teillet writes that Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, the father of the Indian Residential School system, called the Métis “wild people,” “miserable,” and “impulsive half-breeds.” Macdonald wanted the Métis to be “put down, kept down, and kept quiet.”

Roman Catholic Bishop Vital-Justin Grandin, a key architect of the Indian Residential School system, wrote in an open letter to the Saskatchewan Herald in 1880: “I beg your permission gentlemen to the preservation and civilization of the poor Indians. That one hundred Indian and halfbreed children be brought to the mission, when they leave, they will no longer be Indians, being able to become good citizens, earn their own living, and be useful to their country. Should you doubt this, come to our orphanage . . . at Isle-a-la-Crosse [sic] and [you] will see young men of Indian blood by birth, now quite civilized.”

A name for the Métis is otipemisiwak, a nêhiyawêwin word meaning “those who rule themselves.” In the early 1860s, reports from the boarding school at Île-à-la-Crosse showed the children were resilient. They pushed back against speaking and writing in French—the language of instruction at the time—and instead insisted on continuing to speak Cree amongst themselves. The missionaries threatened to reduce visits from students’ families, believing the contact with relatives kept the children resistant.

Food shortages and health problems were common in the school, leading to the death of at least one student in 1865. The mistreatment of children led to community protests and families accused the Oblates and Sisters of Charity of negligence. (The Sisters of Charity of Montreal had arrived in 1860 at the request of the Oblates, who were disappointed with the lack of attendance at the school. Commonly known as the Grey Nuns, they were widely involved with staffing many of the Indian Residential Schools across Canada.)

The school was more of a work camp than an educational institution. Thérèse Arcand, a student in the 1920s, explained that their days started by 6 AM with chores, then a breakfast of porridge prepared by the students, then more chores, then lessons. In the evening, more chores, then bed. The school opened and closed many times due to fires and underfunding, before being permanently opened in 1935. In 1937, my kokum was born.

In 1944, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, the party that would birth the current federal New Democratic Party, commissioned a government report that advocated for an increased number of day and residential schools in Saskatchewan. It called for two federally funded residential schools to be built, with one in Île-à-la-Crosse. In the end, neither school was created due to a lack of support from the federal government and the Catholic Church. But soon after, the province began renting classrooms from the existing school, paying teachers’ salaries and covering costs related to students’ board.

That same year, my kokum was seven, an awasis. Children are sacred. In some stories, it is said that they choose us, and travel time and space to be on this earth. Choosing to be in this human realm is an enormous act of autonomy. The Indian Residential School system took away the sacred autonomy of children. I was told that at night, staff would turn on an electric fence around the school at Île-à-la-Crosse.

In an interview with CTV News, student survivor Max Morin said when he attended the school: “I got a number and we were known by our numbers, not our names … like a concentration camp.” Morin attended the school around the same time my kokum did, and I wonder if she was given a number. Another survivor, Alphonse Janvier, said of his arrival: “I was put on this old barber’s chair. I remember my head being shaved and all my long hair falling on the floor.” Did they cut my kokum’s hair? I’ve always loved her curly dark hair. When I was little, I would watch her brush out the curls while she got ready in the morning.

Survivor Yvonne Lariviere explained that she didn’t understand the reason she was being hit by staff was that she couldn’t speak the language of instruction. “I was seven years old and I had never been hit before in my life,” she said. If I close my eyes, I can picture my kokum sitting at her kitchen table yelling loud Cree into the phone, talking to her brother. Was she punished for speaking our language?

Like many families, we don’t talk about my kokum’s time at residential school. This wound runs too deep. There’s an old Métis story about the roogaroo, a man-wolf who is said to turn you into one, too, if you look it in the eyes. This wound is our roogaroo, an ever-present threat we can’t look at directly. Healing has to come from somewhere other than staring this pain down. It hurts everywhere when we think about it. It hurts through time and space, into the past and present.

Over the years, attendance at the school grew. In 1964, there were 331 students in a school built to house 231. That same year, a fire burned down the boys’ boarding house. In 1972, the school caught fire again, destroying twelve classrooms. After the second incident, the parents took charge. In 1973, the people of Île-à-la-Crosse took over education in their community in an act of defiant self-determination. At the time, my kokum was thirty-six and had eight children of her own. My mom was nine, an awasis herself.

In his essential book Prison of Grass: Canada from a Native Point of View, Métis activist Howard Adams explains that the takeover happened through labour. “The natives of Île-à-la-Crosse took advantage of this situation and demanded that authority over the school be legislated for the local people,” he writes. As highly skilled tradespeople, community members demanded that they be the ones to rebuild the school. Next, they took over the school’s administration and selection of teachers.

Through mass meetings, non-stop campaigning and bargaining, the Métis people of Île-à-la-Crosse succeeded. Rossignol Elementary and Rossignol High School were opened, and they continue to run in the community today. Classes are now offered in Northern Michif (sometimes referred to as Northern Cree). “Métis know that the present institutions have failed them, and that they have a right to take control of these institutions and change them,” writes Adams.

In 2007, the federal government implemented the Indian Residential Schools Settlement. The following year, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was born. Prime Minister Stephen Harper stood in the House of Commons and issued an apology to the survivors of the Indian Residential School system. During this time, we were supposed to heal together, with Canada recognizing its “dark chapter” and Indigenous people bearing our darkest traumas. The darker secret of the settlement agreement is that Métis and non-status First Nations students were not included in this grand gesture.

The legislative muskeg that dictated the history of Métis and non-status experiences of residential school also dictates our mandated healing. Where is my kokum in all of this? After her phone call in 2013, I asked at the TRC witnessing event about the residential school in Île-à-la-Crosse. At the time, the person I asked informed me that the school wasn’t on the official map of residential schools and then gave me a 1-800 number to call. I told my kokum and gave her the number. Defeated, she told me that she’d already called that number—it had gotten her nowhere.

Survivors seeking compensation for their experiences at the Île-à-la-Crosse boarding school launched their first class-action lawsuit against Ottawa in 2016. In 2019, the federal government recognized there were harms done in Île à-la-Crosse. The Métis Nation—Saskatchewan and the federal government signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), committing the signatories to exploratory discussions about how to address the atrocities committed at the Île-à-la-Crosse school. The province did not sign the MOU. Around the same time, a group of survivors signed an agreement with the federal government that would bring compensation for past attendees of the school. Yet there is no timeline on how long this process will take, and no public details are available about what it will encompass.

The Île-à-la-Crosse experience is not isolated. Thousands of Métis and non-status survivors have yet to have their experiences recognized by federal or provincial governments. The lack of federal recognition leaves survivors in a continuous lurch. Since the implementation of the settlement agreement, which recognizes 139 federally run Indian Residential Schools, hundreds of applicants have requested additional schools be recognized under the settlement. These include provincially run schools, day schools and schools run by religious organizations. Applicants have not had their requests granted, and as such, are still left out of the federal settlement. This also renders survivors of these institutions ineligible to access mental health supports funded under the same agreement.

The criteria created by the country that enacted these atrocities continues to uphold the same colonial harm through scarcity in funding and accountability. The schools in question may not have been funded federally, but they tried to do the work of the assimilationist Canadian state. Regardless of who foots the bill, our pain is this country’s legacy.

Now, as the bodies of little ones are being confirmed in unmarked graves and this grief is being ripped wide open, it is time for federal and provincial governments to step into their responsibility. We can’t keep breaking open and filling this country with our mourning, receiving nothing but well wishes and recognition to put ourselves back together. We need answers, we need change. My kokum’s call for answers is yours now too, because I can’t carry this on my own.

My kin, I want you to take a deep breath and close your eyes. Lay your head back and picture the last place your body felt weightless and your spirit felt free. What do you hear? What do you smell? I hear the sound of the wind shaking poplar leaves. Yôtin, I hear the wind make the long prairie grass whisper secrets to the never-ending sunset. I smell earthy petrichor after a late August rain.

Where did you go? Hold that place in your heart and return there when this all feels like too much. Remember what it feels like to pick plump saskatoons from the bush, and the dull thud they make when they hit your empty ice cream bucket. Take a deep breath, and imagine hearing a kitchen table full of aunties laughing, crinkled eyes and open mouths calling us home. These are the things this insurmountable grief can’t take away from us.

Samantha Nock is an âpihtaw’kos’ân writer who grew up in Treaty 8 territory in Northeast BC. Her family comes from Île-à-la-Crosse, SK. Currently, she is located on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Wautuh peoples. She’s been published in Canadian Art, VICE, Room Magazine and Best Canadian Poetry.