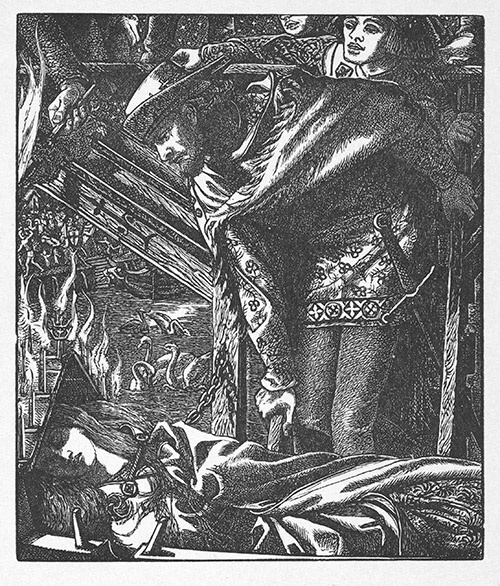

The Lady of Shalott (After Dante Gabriel Rossetti), The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Lady of Shalott (After Dante Gabriel Rossetti), The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Zuhr

Translated by Katia Grubisic

Translated from Rien du tout, published by Mémoire d’encrier, 2021. Reprinted with permission from the publisher.

Mourners are moaning in the streets. I don’t look out the window, I cover the mirrors to delay my own decomposition. The day is fragile, a gust of wind would be enough to pry me apart. In the room I sleep in, a man died of AIDS, surrounded by his friends. His bed was in the same place as mine, head against the brick wall and feet toward the door. He was eccentric, my neighbour the next balcony over tells me, extravagant, he was a faggot, a crazy architect, he would often bring lovers home, he threw big parties. She leans in, the way people come close when they’re about to say something horrible. He got sick, but he asked for it. She claims he hid an electric watch in the wall, but I’ve been here so long I don’t hear the plaster ticking anymore, just the neighbours crashing around above, below, next door. My walls shake constantly. Sadness works the same way, I think: after a while you stop hearing it, the sound becomes part of the air, part of the sky, until someone smacks something and you break the surface for a moment, up through the dazzling madness, you leave the house to extricate yourself before diving back in, get out quick while you still can, and even if the ringing is still throbbing in your skull, get out and walk, out on those same streets, turn a different way, take the noise for a walk like a dead dog at the end of its leash, leave your house collapsing behind you.

I searched, I forgot what I had lost, and even the space left behind by the loss had faded, its outline less sharp. I no longer recognized anything, not even a shape that might have filled it, and soon there was no way to know whether I was looking for love, a cat, a tongue, a glove, a child. The more I looked, the more I forgot. Walking dragged me further into forgetting, and forgetting into that loss. I wondered if it was even mine. Maybe I’d been infected by an endemic, ancestral loss.

In the time it took me to cross the city, I grew old. I could see it in the faces of the strangers smoking on the sidewalk, how they stepped aside to let me go by when usually I get shoved and jostled so much that I might as well be invisible. I was moving forward, dazed by aging so suddenly, and I wondered, were we already dead? There was no trace of our existence in the streets, only a terrible hope that I might find you where we had said goodbye, finding you like a grave or a river, finding you again even if it meant becoming one of those animals that keeps coming back to the same place to lay its eggs, to drink, or to die.

In cafés, buses, departure lounges, fascism is taking hold, a red cap on its head. Out of politeness, we look away. That’s how it takes a seat, settles in; cordially. I fight to keep my eyes open. I am drained—of blood, of any thought, drained even of weariness.

As I pull away from the mainland, my mother’s body unravels. The ligaments that held her together give way. Her bladder drops into her vagina. She gives birth to her organs one by one. We fall apart in different places. Our bodies dismantle themselves in order to go back in time. The hole is an organ and the organ creates its function. The thing under my heart is prosthetic, a dam holding back the sea.

I fall asleep on the plane, dreaming of swans and burning cathedrals. A lost language soothes me, cradles my throat, the language of tenderness and secrecy, conspiracies, the whispered conversations we don’t want the children to hear. I fly over the drowned, over ships spotted and abandoned by the Guardia civil. I show my passport and a woman is shot in the head after being turned away by an officer of the state.

Childhood deformed me. I said that I come from nowhere, that I have no country, no city, only a scorched forest, only the dunes, the rocks and the tide. I keep quiet, there are too many things in my mouth—fingers, accents, geographies. I cling to the vestiges of loss. This is mourning without having anything to mourn, a transferred silence, contracting like a heart or a disease. There will be no trial. I will escape into a language but never find shelter there.

All the mouths are filled with cement, the mountains have coagulated. In a village of blackbirds and red earth, a woman learns to count to the age of her children. The grey cat gave birth in the garden and then wasn’t seen for weeks. When she came back, there were no kittens with her, and the keeper says she must have eaten her litter. Here, madness is concealed, though it catches up. A homeless woman limps nowhere, rocking unevenly on the spot as if she were sinking into unseen mud. In one hand she clutches a torn plastic bag, covers one ear with the other, her mouth distorted by voices no one else can hear. Be careful, my father says, or you’ll end up in Berrechid, where they send madmen before forgetting them entirely. My father’s rigid shoulders hollow me. I would like to stroke the dark circles under his eyes, to pour the warm sand of the country he left over his body. My father is shrinking and soon I’ll be able to cradle him, I will carry him over my forearms, I will lay him in a citrus grove. In the meantime, I eat the crumbs of his memory of his country. I keep the word, Berrechid, in my mouth, trace it mutely with my lips and my tongue, a silent litany.

In every city I look the same, the knotted muscles of my face lose the habit of the language and I have to dig around in the sleeping corners of my mouth. I recognize a script as I cross the douar: caves, nights full of bodies warming, the iron smell of childbirth, and numbers, counting in the language of the other. I learn not to look away. ✲

Olivia Tapiero is the author of Les murs, which won the Prix Robert-Cliche and was a finalist for the Senghor Prize, Phototaxie (Phototaxis, trans. K. Schluter) and Rien du tout, from which this excerpt is taken. She co-edited the collection Chairs, is on the editorial board of Moebius, and has contributed to numerous publications, including Estuaire, Liberté and Tristesse.

Katia Grubisic is a writer, editor and translator. Her work has won the Gerald Lampert Award and been shortlisted for the A.M. Klein Prize and the Governor General’s Award for translation.