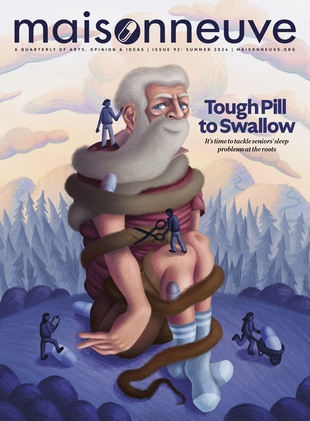

Illustration by Lisa Vanin.

Illustration by Lisa Vanin.

Shh

My copy of Gray’s Anatomy lies sprawled out

on the kitchen island, stranded and battered.

It is just one of many medical books scattered across the apartment. Bound in frayed red silk,

spine snapped, it wears the marks of my violence as

one who’s resigned to its fate—from makeup stains

to brown cup rings. Red pen marks run through its

white pages like a network of exposed veins.

I’ve recently become obsessed with what goes

on inside my body. Not the body, but my own body.

I’m trying to figure out the parts of me that are

perpetually in pain, the kinds of pain that no one

can see because there are no bruises or physical

wounds to point to on my black skin. It’s like all

the places that ache inside me are wearing a cloak

of invisibility.

When I go see my doctor, he makes jokes about

the “general” in his title. He laughs and laughs and

laughs and then prescribes painkillers that don’t

last. When I become a bit frantic and insist that my

pains are real, he hands me forms filled with boxes

and check marks.

“If something is there, it’ll show up in your blood,”

he tells me. I resist the urge to ask him what if nothing

shows up—again. What then? Can blood not tell lies?

That night, I dream that my body is streaked

through with lightning as sharp as razor blades.

White-hot bolts of pain ignite in my lower back but

shoot up my spine to my head. The migraine is heavy

enough to keep me under, asleep. The pain clogs my

throat and shows me premonitions of terror—eyeless,

mouthless shadows that make the bile in my stomach

rock back and forth.

When I finally break through the surface, I crawl to the bathroom, retching the whole way. The

featureless shadows follow me from sleep and hover

over my sweating, shivering frame in the dark on the

bathroom floor.

As I wait for the oven in my brain to cool down, I

think about all the things that have ever happened to

me. If I concentrate hard enough, I can remember a

time before pain permeated every part of my life—a

time before my body betrayed my youth.

High school sock hops. First kiss do-overs in dark

stairwells. Scouring the lakeshore for perfect disc-shaped stones.

Now, the world is filling up with things that trigger

all my invisible pains. The bathroom is full of them.

Fluorescent lights. The incessant ticking of the baseboard heater. There’s a cilantro-scented candle my

boyfriend loves to light. I used to be able to tolerate

the scent, but now it reminds me of the way cilantro

tastes of soapy weeds.

I make it back to bed but can’t fall asleep without dissolving a pill under my tongue. By now, the

migraine is a dull pulsing at my temple. My eyes

are clearer, and the shapes in the dark slowly fade; I

almost miss them. If that sounds like madness, then

perhaps it is. Maybe madness is the accumulation of

a life lived in pain, and pain is the only way to be as

alive as possible.

I pay for the blood tests because hospitals are

spilling out onto parking lots, and I can’t afford to wait.

The nurse at the medical lab who tries to draw my

blood does so blindly. She binds my arm, taps the

brown ridge in the crook of my elbow, and sticks the

needle where my veins should be visible, her aim a

mere guess.

The vial stays empty, and my stomach fills up with air.

“Maybe try the other elbow,” I suggest after a few minutes. I’m

barely taking breaths, and the walls around us are slowly closing

in. It’s clear from the way she presses her lips that she does not

want to be told how to do her job. There are special rules that

exist between nurses and patients. Rules that lean heavily on

her side and give her authority over my body and what’s being

done to it.

She shifts the needle around, coaxing my blood to reveal itself.

Her light-pink fingernails dig ridges into my flesh, an extension

of her body sending pain into mine.

A flutter of anxiety grows in my stomach, making me feel sick

and cold. I want to tell her to stop. Beyond the window, the rain

begs me to be quiet.

Shh.

Shh.

Shh.

It feels like the whole world has been saying that to me from

the start.

The pains started on a Tuesday morning at the beginning of winter.

It was my first year at Dawson College. I was studying law and

society and sharing a small one-bedroom apartment with my

best friend, Noémie, in one of those red pre-war buildings from

the 1900s. There was one heater controlled by our granite-faced

landlord and an ancient gas stove that hissed loudly if you turned

its dials too high.

I woke up restless after failing to sleep more than three hours.

I could hear Noémie’s snores coming from the living room where

we’d set up a “nest” made of all the soft things we could afford

on a student budget: a bread-thin mattress, a pile of blankets

and pillows, old sweaters for extra padding and warmth. We

took turns every other week on the twin-sized mattress in the

bedroom—our idea of luxury.

Not wanting to disturb my friend, I tiptoed to the front closet

and grabbed my windbreaker and running shoes. Jogging usually

cleared my brain of any foggy debris from a night spent between

sleep and wake.

A steady freezing rain fell, making the air hard as I walked

out the front door. The season was just getting started, and

frost coated everything: the trimmed-back branches of trees,

the cracks in the pavement, even the mud in the construction

sites was firm with it.

Somewhere in between one chemin and another, I started to

run. Below-zero-degree temperatures seep into your pores like

pins, but it was a pain I was familiar with and knew would melt

away as my body warmed up.

I remember how good I felt in that early morning moment.

No cars rushed by, honking hostilities. No one pushed past me

speed-talking into a cell phone. I was alone in the world, and

that aloneness was like a salve for my sleep-deprived mind.

I don’t know how to put into words the violence of the pain

that knocked me to the cold ground. Except to say I felt it too

much and everywhere at once.

Coal fires burned in my head, chest, and rib cage and sent a scorching-hot nausea rolling through my stomach. It was the most physical thing I’ve ever experienced.

The pain took my breath and pressed down on it so hard that

every exhale came out as a wheezing noise. When I tried to stand,

bright flashes made my head spin. There, on the deserted street,

under the indifferent sky, all I could do was fold into myself like

a pocketknife while the pain spread through me. I thought if I

squeezed myself small enough, there would be less of me to hurt.

It didn’t last long; it didn’t need to.

It didn’t last long; it didn’t need to.

Only when I found my breath again did I know I’d survived.

During the next Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, regular bouts of pain kept me confined to my bed and away from my classes. Each time, I searched the outside of my body for signs of what was going on inside. A bump or bruise. The purplish tint of a rash rising through my flesh. My skin gave nothing away.

By the time Noémie convinced me to go to the hospital, I’d

started thinking of the pain as a growing thing. It swam through

my veins like a swarm of red ants, adding fog to my brain and

cataracts to my eyes.

I’d tried everything to kill it. Drowning it under freezing cold

water in the shower, poisoning it with aspirin and dépanneur

rum. Nothing worked.

At the hospital, the receptionist gave me a sour once-over. “It’s going to be a long wait.” She said it flatly, her grey eyes so hard they gave the impression of stones at the bottom of a frozen pond.

“How long?”

“Can’t say for certain, but you’re looking at ten hours. Minimum.”

“I don’t think I can wait ten hours.”

“You don’t have much of a choice.”

The sound of files being tapped twice against the counter

signaled an end to any attention she was willing to pay me.

I searched for something significant to say to convince this

woman how dire my situation was, but someone cleared their throat behind me. Whatever I was going to say fell away, and I

felt myself dissipating to a black point, an eye floater in the great

white blur around me.

The waiting room was crammed with people struggling

to find comfort on the worn-down plastic chairs or leaning

against the white-grey walls. Most of their ailments were visible. A black eye, a broken arm. An older man wore one pant

leg rolled up, an angry red rash splashed across his pale calf

like spilled jam. He stared at me, and I wondered if he was

looking for proof that I belonged there—physical proof that

my pain was as real as his.

Time moved slowly, oozing along, molasses-like. Everyone

tried for stillness. Whether they meant to or not, they hummed

and moaned in the antiseptic air while, one by one, names were

called—Bennett, Laurent, Martine, Wilson—and bodies changed

chairs with new moans and new wounds and more waiting.

I sat where two walls met—one bright under a stabbing bulb,

the other in shadows—and rested my head in the corner, concentrating on breathing in and out. The pain pushed its way

through my body, warning me to stop moving. Even breathing

was moving.

It was around 2:15 AM when someone finally called my name.

I heard it in the watery way sleep tries to drown out the world

and make all its trouble weightless. It took me a few seconds to

adjust to the light, a few more to notice the absence of the spiked

thing that had stalked its way through my body for days. In its

place was a nice fuzzy feeling, like being drunk or high or both.

The nurse didn’t wait around to see if anyone followed. She

moved like the wind; keeping up with her was like wading

through warm milk. She was my beacon in bright purple scrubs.

In all this whiteness—white walls, white floor, white doctors in

white lab coats—she shone.

Maybe it was the time of night. Maybe it was my new buzz.

But, everything about her was rapid; the device she aimed at my

forehead, the way she pumped and pumped and pumped my

arm with the blood pressure cuff. She spoke a quick-fire French

that had me grasping at words like I was catching snowflakes

in my sweaty palms.

“So what brings you here?” she wanted to know immediately.

“Um … well, up until a few minutes ago, I was in a lot of pain.”

“And now?”

“Now I feel better than I have in three days.”

“So, you don’t need to see a doctor?”

“No, I’d still like to see one.”

With that, she hmmed to herself and left the examination

room without another word.

Shortly after, the odour of cigarettes, coffee, and cologne

forced their way into the room with the doctor. He was young,

or looked like he was, with slicked-back hair and a Mad Hatter

bow tie. He made me think of those men who never outgrew

their college days and ways—the ones who did surprising things

to be as visible as possible.

“Well, well, well, what do we have here?” he asked in a singsong

voice that matched the tie. He regarded me with something more

than medical curiosity. Something physical, like a hand on my thigh or at the base of my spine.

While I described the last three days of my life, he listened to my chest, back, and lungs. Peered into my eye sockets with a flashlight and a smile.

“And on a scale from one to ten. How bad was the pain?” he wanted to know.

“About a ten,” I replied.

“And now?” he pressed his thumbs into the sides of my throat.

“About a one.”

“So, it looks like I have the healing touch.” He laughed, revealing little black fillings and something green nestled between his molars.

His manner embarrassed me. I was embarrassed that he wasn’t taking me seriously, embarrassed that perhaps I wasn’t explaining myself well enough to be taken seriously. I thought about my mother, about the doctor who had pinched her nipple and winked at her.

“How does that feel?” he’d asked.

I remembered Mom’s outrage and her silence. She had vowed never to return to that hospital but chose never to report the doctor. I vowed to be different, better.

“What do you think caused it?” I asked, keeping my voice level.

“Sounds like you just had a migraine,” he offered.

“So you think I’m fine?”

He reached out and touched my arm. “I’d say you’re more than

fine,” he said. “You’re perfect.”

We are thinking of each other’s blood—the lab nurse and I.

She holds mine in her hands, collecting it in five glass vials with

labels I can’t read. Blood colours her cheeks, ears, and chest—a

crimson shade that belongs to cold weather, passion, and pain.

For a moment, I think I can see everything below her skin.

I try not to look at the place where the needle is siphoning out what’s inside my veins. But it’s hard to look away when blood is the only visible thing that connects me to what goes on inside my body. The slow red drip of it fills my head with hot air and makes me feel so light I float.

“Almost done,” the nurse says.

I feel the pinch of the needle on my arm and think about my

medical books. I think about Gray’s Anatomy with its tattered

cover and gold lettering. About its ripped and wrinkled pages

with Henry Carter’s black-and-white illustrations of arteries,

bones, and organs, and how good it feels to press on its spine

and dig into its pages with my pen. I imagine holding Gray's

pages between my teeth—pages without mention of the word

pain—and thinking of that word, biting down on the textured

paper and tasting its bitterness.

At least you don’t have to worry about bruising,” the nurse says, popping the last vial from the syringe and mopping my arm with a cotton swab.

I want to say something, to tell her that just because my skin hides its bruises doesn’t mean I don’t feel them.

Beyond the window, the rain begs me to be quiet.

Shh, shh, shh.

I listen. ⁂

Chanel M. Sutherland

won the 2021 CBC

Nonfiction and 2022

CBC Short Story prizes.

She was awarded

the 2022 Mairuth

Sarsfield Mentorship

and longlisted for both

the Commonwealth

Short Story Prize and

the Room Short Fiction

Prize in 2022. She was

also included on the

CBC Books 30 Writers

to Watch list for 2022.