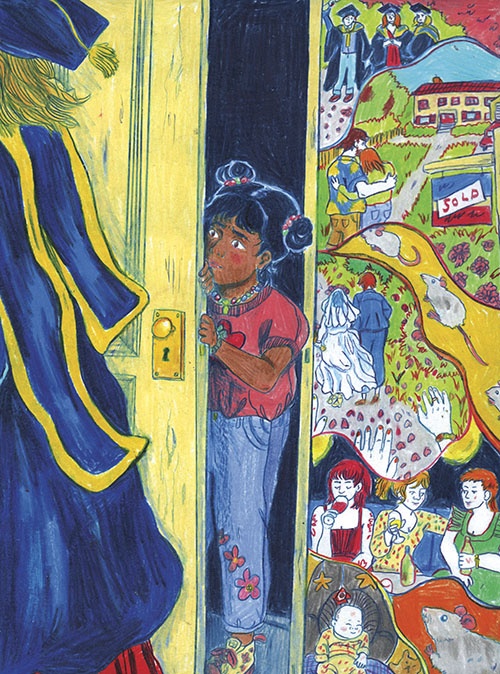

Illustration by Hannah Lock

Illustration by Hannah Lock

Mouse House

“‘Priate-qui? Priate-qui?’ (pryatki, hide-and-seek), she uttered ...

‘Sichasse pocajou caroche messt’ (seychas pokazhu koroshee mesto,

right away I’ll show you a good place).”

—“A Bad Day,” Vladimir Nabokov

Amba’s mother tried to send her to the party in an Uber, but when she started climbing into the front seat of the car, the driver shook his head. Maybe she was supposed to sit in the back? So she got out, shut the front door and opened the back door.

“Jesus, I can’t drive you without your parents,” he said.

“Oh,” she said. The car smelled of artificial pine, and she held the door open longer than she should have.

“The air conditioner’s on,” he said. “Tell your parents to call a taxi.” The car had already started to move.

Her mother first chastised her for not forcing the driver to wait, then googled the price difference between an Uber and a cab. She checked the time to see if she could drive Amba herself, and then called a taxi, but taxis don’t just hover around in the suburbs expecting to be needed. So Amba watched the driveway, counting the minutes, slumped by the living room window like a frog in a terrarium. She would be late to Sophie’s birthday party. Now they were choosing the first game without her. Now they were drinking homemade raspberry Italian sodas without her, Sophie swirling a paper straw in the tall glass until the paper dissolved.

The taxi arrived, yellow and slow.

“Remember, don’t be shy,” her mother said, without smiling, as Amba got into the car.

The first game was Pin the Tail, with a unicorn instead of a donkey. Sophie’s mother had drawn it and tacked it to the curved wall of a foyer so large it could have held a parade of actual unicorns. On the drawing the mane and tail were purple curlicues, spilling across the white muscular body. The hair looked like Sophie’s, though hers was not purple but a cold shade of blonde. Instead of the tail, they were supposed to pin the horn. There was a whole pile of horns twitching in Sophie’s mother’s hand, cut from a rainbow of construction paper. But weren’t they too old for this game? Hadn’t they played this game last year, with a paper horse? Hadn’t Sophie’s mother stretched a black bandana over the eyes of each child, then held their shoulders and turned them until they’d lost all sense of direction? In fact, wasn’t this the same drawing, with the addition of a permanent tail and add-on horns?

There were too many people at this party. There were more than thirty. In her own house, there were never more than two. Amba had hoped Sophie’s cousins wouldn’t be there and that it would just be people from their class. When she arrived, everybody had swivelled their heads to look at her for exactly one second, said nothing and then turned back to the game. The Cousins had previously lived somewhere like California or Florida—places Amba conflated with each other (heat, Disney theme park)—but they had moved to town and were now always around Sophie, like Secret Service agents, like a hula hoop made from humans. There were seven or eight of them of different ages, but they all got along and had inside jokes. “I love scotch,” they’d all sing together. “Scotchy, scotch, scotch.” This meant nothing to Amba.

Amba had most looked forward to eating. When guests came over, Sophie’s mother would present soft, round cheeses with white rinds next to anise seed crackers fanned across dark wood boards; figs brimming in a bowl. Sophie’s mother would treat the children as though they were not children but aristocrats. With tea she would serve a brioche so symmetrical it could have been 3D-printed, and then she’d say the dough hadn’t risen to her liking. The birthday cake would taste like witchcraft. Alone at home after school, Amba watched hours of cooking shows, ones where pastry chefs in pastel-coloured coats built improbably tall, wobbling cakes, as off-brand Oreos churned into black paste inside her mouth. She imagined Sophie’s cake with a sculpted chocolate number seven at the top. She hoped the frosting would be the same as last year—like no other frosting on Earth. She remembered the pronounced taste of salt.

But first, the games. When Sophie’s mother left them alone, Amba feared the real game would be for the Cousins to blindfold someone and point them the wrong way. They would choose the child most easily made a fool, facing her toward the basement stairs, first as a joke but then with curiosity. How would the fool react?

She had seen the basement before, on a dare during a sleepover with Sophie and another girl from their class. That was before the Cousins had moved to town.

“For this dare,” Sophie had said, widening her far-apart eyes in an impression of a maniac, “you can’t turn on any of the basement lights. You have to go to the trunk, open it and bring us back something from inside.”

They’d been telling scary stories, and this was a natural consequence.

So Amba had taken the long, horrible walk out of Sophie’s room, away from the two girls who had already begun to whisper secrets she would never know, through the upstairs hallway that smelled of paint, down the curved wood stairs, past the low blue light of the living room where Sophie’s father huddled asleep and alone in front of the television, arms crossed in front of him, volume turned off. The house clicked with quiet sounds—a fridge, a clock, someone’s phone. On the carpet, Amba’s steps disappeared. She hurried down the basement stairs with fingers skimming the railing.

At the bottom she paused, mapping out her path. The space had an identical perimeter to the first floor, but with no rooms at all. Square pillars were scattered across the dark. It was a graveyard for furniture, each piece covered in a white sheet as though an unspeakable murder had occurred here and the family had gone to the country to re-evaluate their priorities.

In one of the far corners was the ominous trunk. She held her breath and ran through the basement, shoulders pulled in, feet like the frame of Muybridge’s The Horse in Motion where all the horse’s hooves are undeniably in the air. She flipped up the brass latch and cracked open the heavy, dusty lid. Unwilling to reach her hand blindly into the trunk, she turned on her cellphone light and looked inside. It was empty.

The origin of the dare: At school, all three girls had read a story about a bride, a groom and their guests playing hide-and-seek after their wedding reception. This didn’t seem like a wedding activity to Amba. During the game, the bride had vanished. They couldn’t find her anywhere. The groom moved on to other endeavours. It was decades later when a cleaner opened the trunk and found her rotted body. The story ended there. What wasn’t described: Lace draped over her skeletal wrist. Flesh eroded away from the teeth. Face ossified in a scream. A complicated smell—sulfurous and sweet mixed with cedar. None of this was the scary part. The scary part was that they had stopped looking for her.

Pin the Horn on the Unicorn unfolded like a ceremony. Someone turned Amba around. She could sense their height from the position of their hands—the person was taller than her, and she wondered who it was. She felt the edges of paper with her fingertips and taped her own triangle of paper down somewhere among the others. She didn’t care where the unicorn’s forehead was. Winning didn’t matter. What was important was survival. On the other side of the blindfold was a bored silence, but she could sense the uneven breathing of the other children, and so she knew they were still there.

“Let’s play Mouse House,” said a Cousin who looked about thirteen and had a single burst of red hair on his forehead, like the curled peel of an orange.

“Mouse House!” exclaimed the Cousins in unison. The game was a variation on hide-and-seek, one they had been playing for years, since before Amba’s birth. While she waited in the wet insides of a womb, Cousins had ducked into closets and hidden behind coats, slipped under beds and porches and into the stomachs of trees. Perhaps hers had been the best hiding place, because she’d been tethered there, visible only by ultrasound, felt only in the slight press of foot against belly as she fumbled for the door to the next world.

Over time, the Cousins had added to and modified the game’s rules in ways that were too obscure for an outsider to follow.

“Some mice hide together,” chanted two of the Cousins who seemed to be twins, though there was something incongruous about one of their faces.

“Some mice hide alone,” said orange-peel Cousin.

“Some mice quietly run,” added the smallest Cousin, the one who most resembled a mouse, her arms covered in thick, soft hair.

“Some mice find their way home,” said orange-peel.

What the heck did this mean? The other folks from Amba’s class looked as confused as she was. Amba tried to catch Sophie’s eye, but Sophie’s eyes were rolling wildly, her hands clapping an erratic rhythm, as though there was so much fun to be had that her body could no longer control itself.

Three of the Cousins began to count down from thirty. “Thirty…twenty-nine…twenty-eight…” The rest scattered. Amba’s brain flipped through various options: in the cupboard under the kitchen sink, in the forest of coats in the hallway closet, under Sophie’s parents’ bed upstairs—nowhere was off-limits. “Twenty-three…twenty-two…”

She chose the basement because she thought Sophie might hide there too, and then they might hide together, and she might not have to hide for too long. It was daylight. The shadows of basement pillars and objects fell in predictable shapes, under wide stripes of sun from the small, high windows. The furniture was as it had been, draped in the timeless fashion of ghosts. Her mind flickered to the trunk, then away.

Amba crouched behind what might have been an armoire, though it may have only been a solid wooden box standing on its end. With the sheet over it, she couldn’t tell. The counting continued so faintly that the numbers sounded out of order. She didn’t know how much more time she had. Thirty seconds was a long time. In thirty seconds, you could sing “Happy Birthday” twice. You could tie seven pairs of shoes. You could wolf down a slice of cake and ask if you could please have another. Thirty seconds could be an eternity. In thirty seconds, you could say the wrong thing to the wrong person in the wrong place and ruin your whole life.

In the distance the counting faded, seeming to get further away. Amba could no longer make out the three reedy voices. She didn’t hear them say “zero” or “ready or not, here we come!” Most likely she was not ready. If someone found her, she hoped it would not be one of the Cousins. A Cousin might crawl out without warning from the corner of the armoire/box and crouch there with her until another person found them, and another. A row of children standing there together, backs curled, alert and silent.

For a while, she waited. Now she understood what stories meant when they described ages passing. She wished she had her phone so she could play a game with the sound off or check the time, but Sophie’s mother had collected them all in a basket with a ribbon tied to it. “So we have your full attention,” she’d said. Amba wondered if there were mice there in the basement, if she was playing Mouse House in a mouse’s house. She had seen mice twice. Once, in a pet store cage. They were shivering. One nibbled at its own skin. The pet store employee, a teenage girl with blue hair, appeared behind her and told her that mice spend 40 percent of their waking lives grooming themselves. Amba hadn’t known the mouse was grooming itself. She had thought it was eating itself alive.

The second time: when her first-grade class dissected owl pellets. The teacher had handed each child a photocopied page with diagrams of bones, a set of tweezers and a dense grey-brown mound, and told them to reconstruct the skeleton they found inside. Amba soaked her pellet in water, and when she pulled it out it was earthy and damp. When palpated, it fell apart.

A boy named Ranveer sat on his own at the computer at the back of the classroom. When the teacher approached him, pointing him back to his usual desk, he refused. “I’m a vegetarian,” he said without blinking.

Only then, fingers deep in fur, did Amba fully understand what the pellet was, or rather, what it used to be.

The teacher paused, unsure if she could force Ranveer to do the dissection. Amba knew this from the teacher’s squint, and because she didn’t immediately raise her voice. The teacher might have been wondering the same thing as Amba: Did it matter if the mouse would have died anyway? Could you just say you didn’t want to hold a thing spat from the mouth of a coughing, staring bird? That you didn’t want to touch an animal without its shape, without its soul? When and what were you allowed to refuse?

Amba saw the owl’s swoop and rush, the clutch of its talons, its round black eyes, its singular goal.

Had the mouse known what was happening to her?

Now she was no longer a mouse, just fur and bones and teeth, preserved in a lumpy relic by virtue of being indigestible. Amba assembled the skeleton but was left with an extra bone. She couldn’t match it to the diagram. Who did it belong to?

A mouse existed only to eat and be eaten. It had the most succinct kind of life.

Amba’s knees hurt. She’d been crouching for so long; her hair felt heavy against her neck. She just wanted cake. Perhaps she would go and see what was happening. She couldn’t hear the Cousins upstairs, and she felt anticipatory humiliation—what if they had finished and moved on to the next game? When Amba straightened from her hiding spot, her body felt long. Behind her, her shadow grew, like the shadow of a spider unfolding itself from sleep.

Amba climbed the stairs to the foyer and noticed there was no paper unicorn on the wall. The kitchen, too, was empty. No scent of crisp sugar. No line of gift bags with pink tissue blossoming from their open tops.

She knew in her stomach that the other children were gone. They had finished the game. They had eaten the cake. They had unwrapped gifts and used them and thrown them out. They had grown up. They had gotten university degrees. They’d had jobs and marriages and mortgages and sorrows. They were somewhere she didn’t know. They were somewhere very far away. ⁂

Shashi Bhat is the author of the story collection Death by a Thousand Cuts, and the novels The Most Precious Substance on Earth, a finalist for the Governor General’s Literary Award for fiction, and The Family Took Shape, a finalist for the Thomas Raddall Atlantic Fiction Award. Her short story “Mute” won the Writers’ Trust McClelland & Stewart Journey Prize.