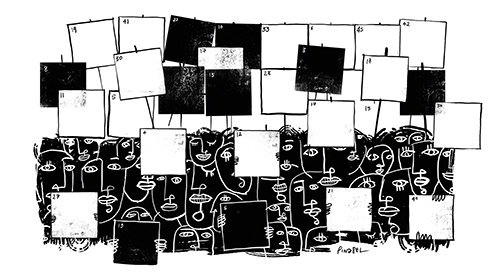

Illustration by Laurent Pinabel

Illustration by Laurent Pinabel

Puzzle Politics

Often dismissed as frivolous games, crosswords can be a force for change.

My backpack is almost always stocked with two books: The Canadian Press Caps and Spelling reference guide, and an anthology of the hundred best crossword puzzles from the New York Times. Every morning, I sling this bag over my shoulders and head to my newsroom, where I sneak in puzzles between interviews and story meetings. Valemount, the BC village where I work, is just two hours from Jasper National Park. Being the newsroom’s only full-time reporter, I became the de facto wildfire correspondent when the site went up in a blaze this past July. My workdays this summer consisted of long, hazy hours of wildfire reporting, bookended by—what else?—crossword puzzles.

Perhaps it’s sheer exhaustion that made crosswords and journalism start to blur together, but as the summer went on, I began to see parallels between my writing and my penchant for puzzles. The click of suddenly understanding wordplay rewarded me with the same dopamine hit that I got from writing a punchy headline. Gleaning the personality of the constructor who created the puzzle by solving their clues felt similar to the intimacy of sitting down with an interviewee and asking them to share their story. I had long understood crosswords as an art form, but I began to appreciate them as serious records of culture and current affairs. Crosswords can touch on niche trivia, with answers like “Edsel,” a bygone Ford car model. But they also commemorate cultural phenomena, by referencing things like “Barbenheimer,” a trend involving a double feature of the tonally different 2023 films Barbie and Oppenheimer—thus reflecting what people were thinking about when the puzzle was created.

My favourite crosswords are the ones that tell a story. If you look closely at the crosswords from Ada Nicolle, who has created puzzles for outlets like USA TODAY, Apple News and the queer online magazine Xtra, you can almost see a narrative arc squeezed into the 15 x 15 grids. Nicolle began pursuing a full-time career in crossword construction around the same time she came out as trans, in 2021. She landed a gig constructing puzzles for Xtra a year later. “All I wanted to do at the time was research queer topics and history and make puzzles that were as gay and trans and lesbian as I possibly could,” she says. Once, when she couldn’t attend the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament in person, Nicolle created a crossword introducing herself to the tournament attendees, with information ranging from the kinds of puzzles she likes to construct to the fact that, at the time, she was beginning to take hormones for her gender transition.

Nicolle sees crosswords as a way to document slang and contemporary pop culture—like a punny version of cultural journalism. “Crosswords are my way of being a bit funny and clever and showing something to the world, going, ‘Remember this? This is a thing that’s worth being in a crossword,’” she says. It makes sense to Nicolle that crosswords can be used as a political medium; they cross whatever’s topical at the time with a constructor’s personal tastes and experiences, making them an opportune channel for commentary.

Crosswords are far more than innocuous trivia. They represent constructors’ interests, beliefs, biases and best guesses at what appeals to their audiences. The same goes for other types of journalism: despite the industry’s staunch claim to objectivity, the perspectives—and prejudices—of those working in newsrooms permeate reporting. Crosswords and news media are lent legitimacy through their publication by media behemoths in authoritative black type. While both mediums are typically seen as apolitical, the editorial decisions that undergird them are fundamentally political. Rather than letting this reality sit in the shadows, some contemporary constructors are making an effort to highlight it. These puzzle-makers are using their skills to bring political commentary to solvers, while challenging the assumption that their crosswords should retain the guise of so-called objectivity.

Although they bear the fingerprints of a constructor’s personality and experiences, crosswords often wind up reflecting the dominant culture. Natan Last, a crossword constructor, writer and immigration advocate, thinks crosswords have the potential to work as melting pots, introducing solvers to vocabulary from other languages or often-overlooked historical figures. Yet, as he notes in The Electric Grid, his forthcoming book exploring the history of crossword puzzles and the lives of their creators, the puzzles often end up being dominated by white American English culture.

“The puzzle certainly privileges anglophone culture, and one of the funny things is that not only does it not have to, it would be a general service to include non-English languages,” Last tells me. “It would make construction easier, it would breathe more life into the puzzle and make it more interesting.” He recalls seeing the Spanish expression “y tú”—and you—in a puzzle constructed by Brooke Husic a few years ago. Despite Spanish being one of the world’s most widely spoken languages, and despite “y tú” making for a convenient entry into a crossword, since “y” and “t” are both commonly found at the end of words, Husic’s puzzle was the first that Last noticed using the expression. He has since seen the Spanish phrase crop up in a number of other puzzles, proving that crosswords can embrace more vocabulary than what sits squarely inside the English lexicon.

In a piece he wrote for the Atlantic in 2020, Last observes that mainstream crosswords “are largely written, edited, fact-checked, and test-solved by older white men [dictating] what makes it into the 15x15 grid and what’s kept out.” Editors, who are overwhelmingly white, cisgender and male, often make the executive decision to tweak clues or entries that they feel aren’t common knowledge. But common knowledge for someone working at an elite institution like the New York Times is probably not common knowledge for the average solver, Last points out. Former New York Times editor Eugene T. Maleska, for example, had a background in teaching Latin, and under his stewardship the newspaper’s crossword puzzles featured Latin vocabulary that probably felt mundane enough to Maleska, but that was likely inaccessible (and, frankly, boring) to many solvers.

When constructors or editors choose to work with very general knowledge in order to cater to the average solver, puzzles can also fall into comfortable predictability. Sticking to routine entries of mainstream trivia limits the medium to an exercise of rote memorization, when it could be used as an educational tool. Instead of trying to guess what trivia the average solver knows, Last thinks constructors should embrace references to other cultures and countries, and reframe lesser-known entries as expansions of what counts as common knowledge. “I think people ought to know who Julius Nyerere, the [former] socialist leader of Tanzania, is. And so when I put that as a crossword clue, I’m trying to say, ‘This should be common knowledge, too,’” he says. “Trying to narrow what you put into a grid and [tailor] it toward what the supposed average solver of the New York Times knows—which is impossible to know—ends up flattening not just your voice, but the potential for interest and variety in the puzzle.”

Last’s comments remind me of the objectivity myth, a term for the idea that journalists can offer completely unbiased perspectives in their writing. It’s an open secret that objectivity often just means perpetuating the status quo. This attitude bleeds into the black-and-white crossword grids sandwiched between reported pieces in newspapers, as crossword editors try to curate universally appealing puzzles. Knowingly or not, crossword editors gear puzzles toward the experiences and perspectives of white, anglophone solvers. As constructor and writer Celia Mattison observes in an article for Catapult, when crosswords include “Enid” as an answer—referencing the children’s book author Enid Blyton—they never mention her history of deeply racist portrayals of Black children. Instead, the white perspective of her as simply a popular storyteller takes precedence.

Catering to the mythical average crossword solver ends up prioritizing the dominant ideology. But crosswords can also be used as political vehicles that challenge the status quo. Leonard Williams, a political scientist and crossword constructor, is the author of Black Blocks, White Squares, a 2021 collection of anarchist-themed puzzles. The title is both a visual description of crosswords, and a tongue-in-cheek reference to anarchist author AK Thompson’s book Black Bloc, White Riot—itself a reference to philosopher Frantz Fanon’s anticolonial work Black Skin, White Masks.

Williams jokingly calls Black Blocks “propaganda by the grid”: it’s meant to educate solvers on anarchist history and organizing tactics, and act as a conversation starter on the topic of radical leftist politics. One puzzle in the book borrows a slogan from an old Industrial Workers of the World poster: “We work for all, we feed all.” Another incorporates the names of the labour organizers behind the Haymarket affair, a famous 1886 demonstration in Chicago. Rather than just providing mainstream factoids, in the hands of constructors like Williams crosswords can force solvers to confront topics they are unfamiliar with, and reflect on the political and cultural baggage they bring to the solving experience. There’s potential for crosswords to expand beyond the rigid box of pop culture and esoteric trivia into a transformative, introspective medium.

Williams spent his career studying political ideologies, with a particular focus on anarchism, and participated in radical groups while protesting the Vietnam War. But Black Blocks was his first project to cross politics and puzzles. When he first started constructing crosswords in the year 2000, mainstream newspapers were his only option for having them published. Even if he had thought to combine his interest in anarchism with his love of puzzles, getting them into newspapers may have been difficult—with money and an institution’s reputation on the line, crossword editors are more interested in keeping puzzles as anodyne as possible. News outlets are financially incentivized to reflect the status quo: they don’t want to risk alienating solvers and losing out on subscription revenue, so find it best to stick to the most mainstream, inoffensive content possible.

Crosswords lend concrete financial support to a paper’s bottom line. The money generated from subscriptions to a paper’s games section, or from advertisements on online crosswords, contributes to the publication’s operations. News stories and crosswords may occupy different pages of a newspaper, but they’re part and parcel of the financial machine that keeps an outlet running. The revenue crosswords generate for media outlets is a crucial piece of the political puzzle that can be overlooked, says London, Ontario-based constructor Will Nediger. “There’s been a lot of discussion in the crossword community about the political nature of crosswords, in terms of them being works of art—but there’s been much less discussion of the fact that crosswords are embedded in a political economy,” Nediger explains.

Case in point is the New York Times Games section, which has attracted over a million subscribers who eagerly wait for daily mini and full-size crosswords, among other games. The section’s monthly subscriptions produce millions of dollars in revenue for the New York Times—not including the revenue from non-subscribers who watch ads to get their daily puzzle fixes. According to the head of the section, these games generate enough money to help keep the paper afloat even as other media titans undergo layoff after layoff.

Constructors who are critical of the New York Times’ reporting have taken note of this fact. Puzzlers for Palestinian Liberation, a collective started by Nediger and a handful of other constructors, has been vocal about the paper’s shoddy reporting on the genocide in Gaza, which ranges from hints of anti-Palestinian bias in language, to whole articles based on later-debunked information. In an open letter to constructors and solvers, the collective argues that boycotting the paper’s games section could lead to real consequences: “As puzzlers, we’re asking you to think of the Times as a cog in the American war machine, and of Games as a tooth on the cog. By breaking one tooth, we can impair the function of the whole machine.” Journalists have made parallel efforts to boycott the New York Times. In late 2023, Writers Against the War on Gaza, a coalition of media workers, academics and culture workers, called for writers to divest from the paper by refusing to contribute either in writing or as interviewees, in protest of its anti-Palestinian bias.

Boycotting the New York Times doesn’t mean sacrificing crossword puzzles for good. Nediger also sees Puzzlers for Palestinian Liberation as an opportunity to highlight the indie puzzle-making scene, which has boomed since the Covid-19 pandemic. “I think we’re in a golden age of crosswords,” he says. “It’s possible to be very choosy about what crosswords to solve, and you still have more than you could possibly solve in however many hours you have in a day for leisure time.” With the rise of indie puzzle-making, neither constructors nor solvers have to support the bottom lines of papers they believe are unethical. Constructors have the independence and flexibility to make puzzles with personality and conviction.

Free-to-use platforms like Crosshare allow constructors to publish their own puzzles online, while outlets like AVCX publish crosswords exclusively, with no news media behemoth attached. Williams, who runs a newsletter with both political analysis and crossword puzzles aptly named Cross-pollination, says the indie boom has allowed constructors to incorporate more radical politics into their puzzles. “Twenty-plus years ago, there weren’t the blogs and independent outlets that allowed for the freedom that people have today. It was more about getting into the major papers,” he says. “Those were not places where having political messages in your puzzles [was] going to sell: they needed ones that were going to be more permanent, that would be more suited to mainstream conventional pace.” Not every crossword has to be radical, but the ability to platform views that challenge the status quo through crosswords reflects a shift in the industry. Rather than having to pass up political expression in favour of staying squarely within the Overton window, constructors can highlight their political influences—and, like Williams intends with his puzzles, get solvers thinking about their own beliefs in the process.

Some constructors have also begun to think about the answers they choose and the clues they write with more intention. When Nediger first began constructing in the 2000s, he appraised his puzzle entries in a vacuum. “Originally, I think because I’m so obsessed with letter patterns, I thought of words as collections of letters. They had value as crossword entries relative to how interesting or exciting the letter patterns were and not relative to their socio-cultural meaning,” he says. “But every choice that you make in terms of what you exclude or include in a puzzle has some political valence.” Similarly, Nicolle makes an active effort to incorporate references to queer culture in her crosswords, even for mundane entries. In her hands, an entry like “elm”—commonly clued as “tree for shade,” or something similar—becomes an allusion to Scream, Queen! My Nightmare on Elm Street, a documentary on the queer legacy of the horror movie A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge. “If I didn’t look into it, I would have just stuck to ‘shady tree,’” Nicolle says. “But going out of your way to find a queer angle for a typical crossword entry, not only is it super interesting, it enriches the constructing experience and hopefully the solving experience. It’s very intentional, and people appreciate that.”

Behind every news article is an opaque set of rules and editorial standards. Don’t begin your opening paragraph with a date. Use vocabulary that’s accessible without being too casual. Make sure your article is fair. Crosswords have similar tacitly understood rules—as Nediger tells me, editors have to strike a balance between keeping a constructor’s voice and interests intact while adhering to house style. Despite this, some crossword constructors have started pushing the envelope, leveraging their art form as an explicitly political medium. These Puzzles Fund Abortion and Puzzles for Palestine, for example, provide curated collections of puzzles in exchange for a donation to a reproductive rights organization or a charity in Palestine, respectively. These initiatives are chances for constructors to hold true to their political values, and to expose solvers to narratives that exist outside of mainstream media.

While there’s a parallel movement among journalists to confront the objectivity myth and address the systemic biases of the media, censorship still abounds in mainstream newsrooms. It’s largely considered taboo to openly discuss how one’s political leanings influence one’s reporting. Still, the thoughtfulness with which constructors like those I spoke with for this article approach their craft provides a good model for improving journalism. Treating every opening sentence, headline and bit of jargon with the same intentionality that a constructor takes to filling a blank grid would translate to more careful reporting.

It’s tough talking to crossword constructors who are so optimistic about their industry’s golden age as I watch the field of journalism collapse around me—but their enthusiasm is contagious. After I finish my interview with Nicolle, I engage in my new weekly ritual of surreptitiously using the office printer to print out a puzzle or two. On that day, it’s the puzzle Last constructed for Puzzles for Palestine, which includes references to Edward W. Said, a Palestinian-American academic, and ACT UP, a grassroots organization working to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The unapologetically political entries are reminders that both crossword constructors and journalists are working to change the media’s focus on mainstream, unobjectionable content. Journalism and crosswords can occupy the same spot in the puzzle of making the media industry more accessible to and inclusive of everyone. They’re both ten-letter words, after all. ⁂

Abigail Popple is a reporter and fact-checker based in Valemount, BC. Her work has been published in This, Xtra and rabble.ca, among other places.