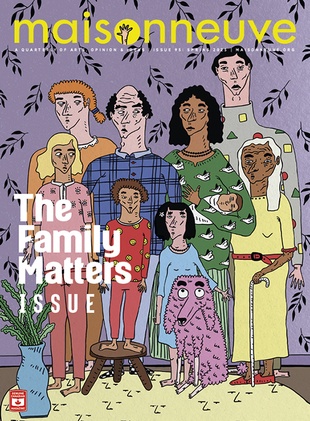

Art by Stewart Jones

Art by Stewart Jones

The Seymour Giant

As BC’s upper Seymour River Valley faces logging threats, a journey inside is undertaken in search of a legendary tree.

It was the summer of 1993, a time when both logging and environmental activism were in full swing in British Columbia. The War in the Woods was raging, as land defenders from Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations and thousands of supporters protested against logging in the temperate rainforest of Clayoquot Sound, on the west coast of Vancouver Island. Meanwhile, deep in the interior of the province, lesser-known battles over forest conservation were unfolding.

One evening that summer, Jim Cooperman, a passionate environmentalist, was having dinner at the hotel in Seymour Arm. The isolated and remote community is located in the Shuswap, a region in BC’s southern interior that takes its name from the lake at its heart. Seated at the table next to Cooperman was a heavy equipment operator working for Evans Forest Products, a company that was preparing to log near the area. The man was explaining to his partner that he had been constructing a road next to some of the largest cedars he’d ever seen.

Having spent much time in the forests near Seymour Arm, Cooperman knew he had to see these trees for himself. It wasn’t until the next spring that he would venture deep into the Seymour River Valley. Located in the Monashee Mountains, the valley contains its namesake river, which flows south down to Seymour Arm and into Shuswap Lake. Cooperman travelled down a road in the mountains with a few staff from the provincial forest service. When he stepped into the snowy old-growth forest, he knew he’d stumbled across something magnificent. “The feeling of going into the forest was [one] of awe ... I found it an experience beyond anything that I had [experienced] before,” Cooperman remembers.

It’s hard to describe the feeling of standing in a forest where the trees have been growing uninterrupted for centuries. People talk about an energy, a sense of peace inspired by the forest’s sheer immensity and a feeling of interconnectedness. There’s also a stillness. Sounds are softened by thick moss on the forest floor, below the tall canopy which filters sunlight into gentle shades. For Cooperman on that day, the majesty wasn’t just from being among those big trees; it also came from knowing that few people had likely been there before. The whole experience instilled in him a powerful drive to protect the forest.

The Seymour River Valley is located in the interior wet belt, a vast region that covers over sixteen million hectares and stretches along the western slopes of the Rocky and Columbia Mountains in south-central BC. Air masses travelling eastward from the Pacific Ocean release moisture into this region as they rise over the mountains, supporting a unique ecosystem known as the inland temperate rainforest (ITR), which is scattered across valleys in the interior wet belt. What makes the ITR so special is that it’s located between four hundred and six hundred kilometres from the Pacific Ocean; temperate rainforests are typically found near the coast, because they need moisture to exist. In the upper Seymour River Valley—the section of the valley north of where Ratchford Creek meets the Seymour River—the trees grow to become enormous due to rainfall, thick layers of snow and the natural fire suppression offered by the climate and the mountainous terrain. Some of the cedars in the valley are estimated to be over a thousand years old.

Forest ecologists consider the ITR to be one of the rarest ecosystems on the planet. It’s home to many lichens that have been deemed threatened by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. The rainforest also serves as a critical habitat for the endangered Columbia North deep-snow caribou herd. The Seymour River sits at the heart of an area that biologists colloquially refer to as “the hub” when discussing the herd, because of its importance to the herd’s survival. Yet, despite the ITR having all the hallmarks of a national treasure, most Canadians do not even have the ecosystem on their radar.

Over the past half-century, the ITR has been increasingly fractured by forest service roads, power lines and cut blocks, which are areas designated for timber harvesting. In a study published in the scientific journal Land in 2021, a group of experts note that in BC, only about sixty thousand hectares of core ITR primary forest—meaning forest that hasn’t been disturbed by human activity—remain. Those authors write that BC’s ITR “is on a trajectory toward what may very well be the most imperiled temperate rainforest on Earth,” with estimates suggesting that core areas could collapse within nine to eighteen years. Yet earlier this year, two North American wood product companies, PWT and Stella-Jones, proposed transforming over six hundred hectares in the Seymour River watershed into cut blocks, according to Wildsight, an environmental group that seeks to protect the regions around the Rocky and Columbia Mountains.

In a renewed effort to bring attention to the recurring threat of logging in the region, I joined Cooperman and a small group of local environmentalists and residents this summer on a hike into the forest to search for the legendary Seymour Giant, a massive old-growth cedar tree nestled deep in the valley. At last measure in 1994, the Giant was a staggering 3.65 metres in diameter. But what’s most notable about the Giant—and what has granted it its legendary status among local environmentalists—is how it may have helped put a halt to logging in the area thirty years ago. The tree has since become a symbol of environmental activism in the region. With the threat of more clear-cuts looming over the forest, there was hope that locating this hard-to-find landmark would remind people of the success that had been won through grassroots efforts, and inspire them to keep fighting.

Cooperman’s passion for environmentalism has guided much of his life. He left Berkeley, California and moved to the Shuswap in 1969, resisting the Vietnam War draft. What helped set Cooperman on the course of local environmental work was a book he read in 1989 called Stein: The Way of the River. The book details the geography and history of the Stein Valley, a wilderness region located in southern BC, and argues for its protection. Cooperman realized there were no groups working to save wilderness areas in the Shuswap at the time. The same year he read the book, he and a group of friends and other local grassroots activists formed the Shuswap Environmental Action Society (SEAS) to unite organizing efforts in the region.

A few weeks after Cooperman’s initial visit to the upper Seymour River Valley in 1994, he returned to get a good look at the area. By this point, four cut blocks had been mapped out, and logging was imminent. He’d assembled a crew of about thirty people, including members of SEAS and other local residents. The group travelled down rough roads to reach the site, and once they arrived, many of Cooperman’s companions were as stunned as he had been by the sight of such a mammoth and magical landscape. But they soon stumbled across one massive tree in particular that captured their attention. It was covered in burls, moss and silver strips of bark. Not only was it enormous, but it’d been left to grow in the forest, untouched by loggers, and thus was a perfect example of the wonders that can occur if nature is allowed to flourish on its own. Seizing the moment, Cooperman snapped a photo of nine members of the group surrounding the Giant. Many of them were dressed in blue jeans and hiking boots, standing hand in hand, smiling.

When the group returned from the expedition, they began a letter-writing campaign to try to pressure the provincial and regional governments into halting logging in the area. Part of the challenge was that Evans Forest Products had already made a significant investment to build roads and survey the site. Cooperman recounts that after getting nowhere with SEAS’s advocacy efforts, he booked a meeting with the then-regional manager of the Kamloops Forest Region. Cooperman describes government officials at the time as being more sympathetic. “It was easier to just walk into the forestry offices and talk to people,” he says. During the meeting, the regional manager was presented with a framed 8 x 10 inch print of the photo Cooperman had taken of the Seymour Giant. Cooperman likes to think the picture, a stunning display of nature’s dominance in scale and size, made an impact. Eventually, the province and Evans Forest Products agreed to restrict logging to half of the planned cut blocks, setting aside about fifty hectares of land and around thirty thousand cubic metres of timber to be left untouched.

The forest around the Seymour Giant was saved. Over the next few years, Cooperman and SEAS focused on lobbying the government and participating in land-use planning negotiations in order to have part of the upper Seymour River Valley placed under provincial protection. In the spring of 2001, a northern portion of the valley was designated as a provincial park. Today, the protected area encompasses over ten thousand hectares and includes wetlands and a floodplain that stretches from the headwaters of the Seymour River to about forty kilometres north of Seymour Arm. But the park only contains a small portion of a vast rainforest that faces the continual threat of logging.

This past summer, during one of BC’s heat waves, I drove down a forty-two-kilometre-long gravel logging road made slow-going by washboarding and potholes to get to Seymour Arm. The off-grid community sits at the northernmost point of the sprawling H-shaped Shuswap Lake. About 160 people live in the community year-round, but in the summer the population balloons with cabin owners, houseboat dwellers and families of campers. Many tourists venture to Seymour Arm because it’s so remote: there’s a mystique to travelling somewhere so out of the way and being surrounded by wilderness. Yet most of the visitors who park their lawn chairs on the white-sand beaches likely have no idea that a Canadian treasure lies just north of them.

I’d come to Seymour Arm to reconnect with longtime resident Lois Bradley, of the Bradley family that has long been involved in local environmental stewardship. Bradley is featured in Cooperman’s 1994 photo of the Giant. When she heard about the plan to hike into the valley again and search for the tree, she was eager to join, and we decided to make the drive together. Bradley’s family moved to the Shuswap in the early sixties, when she was ten years old. They built a home with a view looking across the lake toward ice-coated mountains to the north, and a garden that spills down to a beach. When Bradley and her two older brothers weren’t working, they would go on whitewater canoe and hiking trips. She recalls walking through the valley with her brothers as a teenager, passing lakes and ancient trees as they made their way up the switchbacks of an old mining trail.

“You could just feel those centuries of life. Those trees were so old and carried so much. I would almost think of it as wisdom,” she says. As a child, Bradley had travelled to Europe with her family and visited medieval churches. “When we were first in the old-growth forest, it was like being in those churches,” she says. Her early trips into the valley reinforced her deep connection to the wilderness, a connection that has kept her in Seymour Arm for her whole life.

On the drive north to our meeting spot deeper in the valley, I could sense Bradley’s attention shift to the blur of stumps outside her passenger window. Each stump measured a metre or two wide, and they filled an austere graveyard that had once been part of the forest she’d grown up with. “It hurts to know what [the forest] was and how it has been just ruined,” she says. Bradley thinks old-growth trees should never be logged. “This was not a big asset that we humans gained. We destroyed something for very little value in return.”

Natural Resources Canada reports that in 2022, the forest sector employed over 212,000 people across the country. That year, the industry contributed $33.4 billion, or 1.2 percent, to Canada’s nominal GDP. When it comes to logging old-growth trees, there’s extraordinary financial profit to be made; a large cedar can be worth thousands of dollars.

And yet a 2021 study conducted by environmental consulting firm ESSA Technologies found that old-growth forests are much more valuable to the BC economy when left standing. The study focused on forests around the community of Port Renfrew on Vancouver Island, where protestors had been blockading logging roads for about nine months at the time of the study’s publication. The authors found that the economic benefits of the services provided by old-growth forests, including carbon storage and tourism and recreation, far outweighed the net benefits of harvesting the trees within them. Later that year, the provincial government announced that it would defer old-growth logging in the Fairy Creek watershed and Central Walbran area for a period of two years, protecting over two thousand hectares of old-growth forest near Port Renfrew. The decision had been made in response to a declaration issued by the Pacheedaht, Ditidaht and Huu-ay-aht First Nations, which had requested that their stewardship of their traditional territories, which encompasses the areas, be respected. The Fairy Creek and Central Walbran deferrals have since been extended to February 2025 and September 2026 respectively.

This win was a step toward reconciliation. But the remoteness of the upper Seymour River Valley poses a massive obstacle to this kind of organizing and awareness-raising. The Fairy Creek protest was the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history, with thousands of demonstrators taking part in the blockade and more than a thousand arrests. It would be unfathomable to draw the same crowds of protestors to an area that is absent from many Canadians’ minds.

After driving for an hour or so, Bradley and I pull up to our meeting spot. We step out under a power line that drapes across the forest service road. Delicate yellow buttercups and dandelion-like orange hawkweed grow wild along the sides of the dusty dirt road, before the road turns into rambling forest. Cooperman is there waiting, leaning against his dust-covered Honda CR-V. Minutes later, our other guide, Eddie Petryshen, arrives. On the back of his Toyota Tacoma is a bumper sticker that reads “I’d rather be slowly consumed by moss.”

Petryshen has long been outspoken about the ITR as a conservation specialist with Wildsight, where he focuses on old-growth protection, caribou recovery and land-use planning. As we start up the dirt road, Petryshen stops at a small pile of caribou scat and picks up a piece shaped like a Hershey’s Kiss. “They say caribou used to come right down to Shuswap Lake,” he says, pointing into the distance. We are far from the lake, in an area where few people travel.

Petryshen says that historically, the deep-snow caribou was the main ungulate—hoofed mammal—in the Columbia Mountain ranges. In late winter, these caribou stand on snowshoe-like hooves to reach lichens growing on the branches of old-growth trees in higher elevations; in spring, late fall and early winter, they eat leafy greens in lower elevations. But logging changed the composition of parts of the ITR’s understory, replacing ferns and devil’s club, a spiny shrub with monstrous maple-like leaves, with grass and other herbaceous plants. This new vegetation is favoured by moose and deer, and as these animals’ numbers grew, predators like wolves and cougars followed them into the area. The growing web of clear-cuts, roadways and snowmobile tracks also created more efficient pathways for these predators, making it easier for them to prey on caribou.

According to Wildsight, in 2005 there were eighteen deep-snow caribou herds in BC. Now, only ten are left, and they all face the threat of local extinction. The upper Seymour River Valley is at the heart of the Columbia North herd’s range. It’s where the caribou can spend four to six months foraging for vegetation like the evergreen shrub falsebox, which produces small maroon flowers in the spring and grows along the creeks that flow into the Seymour River. Today the Columbia North herd is an endangered population, with only about 209 caribou identified in a 2022 count, according to Petryshen. It is one of the few herds in the province with a population that has remained stable or increased in recent years, partly due to provincial moose management and wolf cull programs that reduced the number of predators in the area. But logging has threatened that hopeful trend. “We’re at a really critical tipping point in terms of these caribou, because once you get to a certain amount of the forest disturbed, you just see those cumulative impacts. Tipping points get reached, they can’t handle the predation and they disappear,” Petryshen says.

There is, however, one success story in the northeastern section of the province, where the Klinse-za caribou herd has been pulled from the brink of local extinction thanks to an Indigenous-led recovery effort. Representatives from Saulteau and West Moberly First Nations and the federal and provincial governments worked together to protect a crucial caribou habitat by expanding an area called Klinse-za Park. The park now covers about two hundred thousand hectares. Petryshen says that’s just the kind of effort that needs to be extended to other parts of the province, including the upper Seymour River Valley.

The Columbia North caribou herd isn’t the only thing under threat in the ITR; the sprawling forest is home to hundreds of lichen species, dozens of which are dependent on old-growth trees for their survival. Pale-green strands of Methuselah’s beard hang from tree branches like stretchy spider web Halloween decorations. Other lichens, like cryptic paw and smoker’s lung, cling to tree bark in clusters of bluish-grey and brown respectively. Lichens are a main source of food and nesting materials for mammals, birds and insects. Because they get their nutrients from the air and absorb pollutants, lichens can also be examined by scientists as indicators of air quality and climate change.

Many of the ITR’s new lichen species were described by one man: Trevor Goward, who holds the curious title of the University of British Columbia Herbarium’s co-curator of lichens. For decades, he’s worked to bring attention to the lichens of BC. Goward says he coined the term “inland temperate rainforest” in the early nineties, in the hope of bringing attention to what he calls a made-in-Canada ecosystem. While there are inland temperate rainforests in Russia and Siberia, Goward says much of those rainforests have been logged.

According to Goward, the ITR contains antique forests—forests that have developed without large-scale disturbance for many centuries or millennia, longer than the oldest trees have been around. “They’re multigenerational forests,” Goward explains. “They’re not like normal old-growth forests, which burned and then got started, you know, three or four hundred years ago. Some parts [of the ITR] have been dated [at] over a thousand years, where there has not been any indication of fire at all.” Not only is there a sacredness to a landscape so old, but the forest also serves as a kind of archive that records the undisturbed history of the area in its soil and layers.

Yet for as long as Goward has been trying to rally awareness of this globally unique rainforest, he, and, for the most part, the lichens he’s described, have been largely ignored. “I feel like that Greek character Cassandra, who is trying to warn everybody that, you know, things are not looking very good, but nobody would listen,” he says, referencing the mythological Trojan priestess whose accurate prophecies were never believed. “We have a phenomenon that in [many other countries] … would be understood as something equivalent to a cathedral or an art museum,” Goward says. “It would be something that people would go to and admire.”

When given a chance to visit the ITR, people take advantage of it. In 2016, a provincial park called Chun T’oh Whudujut Park, or the Ancient Forest, was established in central BC. The park protects a portion of the ITR on the traditional territory of the Lheidli T’enneh First Nation. Visitors walk down the 450-metre-long boardwalk to experience the ITR’s magnificence. The main attractions are the thousand-year-old western redcedars, but the Ancient Forest is also home to a rich range of plants, mosses, fungi and lichens. Goward says that when people see the forest, they feel that it’s special. “But as long as it’s just a something on a map, nobody really cares,” he says.

Bradley feels similarly about the upper Seymour River Valley. “We don’t even realize what we’re losing because so few people have experienced it,” she says. For people like Bradley, who knew the forest while it was still intact, it’s heartbreaking to think that many question the value of protecting old-growth forest. Yet, given the remoteness and inaccessibility of the upper Seymour River Valley, the calls for conservation are all too easy to ignore.

As Bradley, Cooperman, Petryshen and I venture into the forest, we slowly scrabble up and over fallen trees that have become nurse logs for saplings. Streaks of sunlight stream through the tall cedar branches. The first prominent old-growth tree I see is a cedar that pierces the sky like a sceptre. Ribbons of bright orange flagging tape have been left to hang from a few of its bare branches. Nearby, other trees have been spray-painted with neon numbers—the markings of a timber cruise, used by foresters to estimate the volume of timber in an area.

According to Petryshen, this section of the forest had been designated for clear-cutting a few years back. But the plan was met with significant pushback from Wildsight, members of First Nations and local Shuswap residents. Wildsight led a campaign that saw well over a thousand people share their opposition to the proposal with BC’s Ministry of Forests. The provincial government eventually announced the deferral of logging in the area.

These wins are never guaranteed, though. While clear-cutting has been deferred for certain sections of the ITR, proposals have been allowed to go forward for other parts. In an emailed statement from September, a representative from BC’s Ministry of Forests notes that Stella-Jones and PWT’s proposed cut blocks in the Seymour River watershed are currently under review. They also write that in the region, “some areas are deferred or conserved as part of [a] mountain caribou recovery strategy, some are part of old growth management areas, and some are part of the timber harvesting land-base that support sustainable forestry and local jobs.”

It’s mid-afternoon by the time we assemble back on the road, and we decide to start searching for the Seymour Giant. The last time Cooperman saw the tree was twelve years prior. Back then, he and a few other adventure seekers had been able to drive and then bike the entire way to the base of the tree. The road has since been thoroughly rewilded, becoming a thick tangle of alder.

The plan was to hack our way through the twisting tree branches and devil’s club to get to the base of the Giant. But it’s tough going. After an hour and a half of slow hacking with machetes and saws we stop, and Petryshen brings out his GPS, which shows we aren’t even halfway there. For as far as I can see, it’s nothing but a kaleidoscope of greens, the shades of a young forest growing up out of a clear-cut. No one wants to admit defeat, but it is late afternoon and we have no more water. The Seymour Giant is out of reach, the massive old-growth tree left unseen for at least another season.

We say our goodbyes with a promise to try again next year. Bradley and I hop in the truck to drive back to Shuswap Lake. On the way back, she tells me that in the eighties, she and her brothers had organized a petition to protest logging on Blueberry Mountain, down the lake from Seymour Arm. She remembers a couple of loggers coming to her house to talk it out in the living room. Bradley says nothing was achieved by the conversation, but she does remember one of them admitting that they should never have logged in the Seymour River Valley.

That line stayed with her then, and echoes now. “This valley should never have been logged in the first place,” she says. “But I also feel if we were to step back now and give it time, the valley could heal. The life is there, and it could become that again—but we have to say this is worth our time, this is worth making this effort to preserve the whole valley.”

Stepping into the ITR off the dirt road, away from the power lines and trees flagged with bright orange ribbons or marked with neon-coloured spray paint, it’s impossible not to be moved. It’s like looking up at the Milky Way on a clear night; the sheer significance of an untouched natural world is humbling. And yet, ironically, for it to remain untouched, it must be recognized. Some of the most memorable successes in old-growth forest preservation in BC have come from protests that have made headlines, led by land defenders and local communities who have taken up the fight and put pressure on the government. In the case of the ITR, there may not be as many loud protests, but there are people devoted to protecting old-growth forest. And there is the legend of a tree, the Seymour Giant, left on its own in a remote valley. ⁂

Jennifer Chrumka is a writer and award-winning journalist who worked with CBC Radio for over fifteen years. She’s currently based in Kamloops, BC, where she teaches journalism at Thompson Rivers University.