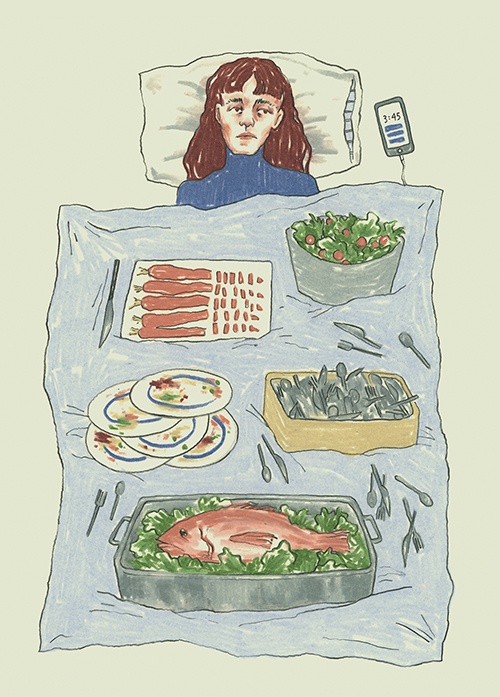

Illustration by Cole Degenstein.

Illustration by Cole Degenstein.

Friends and Family

I had been back in Brooklyn for just over a week when I got a job catering film sets that Jamie, a classmate from college who worked at the company, had posted on Instagram. The morning after I saw the post, I dressed in all black and took the subway to Queens, where I walked to a building Google Maps insisted was still a strip club. After double-checking the address, I followed a guy dressed in a black hoodie and jeans into an industrial kitchen. He directed me to a short, heavyset man at a desk behind shelves of metal chafing dishes. The man, whose name was Paddy, asked if I was looking for full-time or part-time work.

“Part-time?” I said.

Paddy wrote my name and phone number in Sharpie at the bottom of a sheet pinned to a bulletin board and asked what else I did for work. I had been teaching English online to students in China, but my account was suspended after sleeping in and missing too many classes.

“I’m an English teacher,” I said. “Freelance.”

I thought this sounded more official than saying I used to work for TutorWow!, but when Paddy repeated “freelance teacher” in his Irish accent, I realized it sounded just as made-up.

Paddy started me on cutlery while I waited for Jamie. I filled a pitcher with hot water and vinegar and brought it to the table where the other caterers were polishing forks and knives with blue cloths. A middle-aged woman with dyed blonde hair named Tara told me to try to sort the cutlery. The bins were in disorder, heavy forks and knives with ornate handles mixed in with cheap Ikea ones. I grabbed a rag and started talking to another caterer named Ciarán. I asked him how long he’d been working in the kitchen. He said he’d only been there since he left Dublin six months ago, and that almost everyone had been working there for only a couple years. Most people wanted to work on film sets, not cater them, and they left as soon as they got a production assistant gig.

“Is that your goal?” I asked.

“Not anymore.”

Soon Jamie arrived, but only to ask if I wanted anything from Dunkin’ and then disappear again. By the time she resurfaced I had finished polishing forty sets of cutlery. She showed me where to gather the chafing dishes. Most of them were stuck together with hardened grease and food scraps.

“You’re supposed to clean out the chafing dishes before putting them back on the shelves,” Jamie said. “But everyone who works here is fucking lazy.”

I followed her as she gathered tablecloths, napkins, Styrofoam bowls, paper plates and plastic cutlery. She warned me that the cans of fuel for heating the chafing dishes couldn’t be packed with the food as we went into a walk-in fridge to get the salads, which she said she usually skipped because it was annoying to deal with all the little bowls and spoons. Our red meat for the day was pork, so we had to sharpen a knife and bring a cutting board and gloves with us. Jamie didn’t bother with soup or buns and butter, but Paddy didn’t care. She’d been a caterer for three years—longer than anyone else at the kitchen—and had earned the right to skirt the rules.

How’s it going? my mother texted.

Really good, I replied. I think I just needed something more hands-on!

Jamie started loading the van and sent me to the basement to get her condiment kit from a walk-in fridge, but Ciarán was standing at the bottom of the stairwell.

“What’s the hurry?” he asked.

He led me to a room lined with mirrors where he said the strippers used to get ready, and then to a smaller room where he said the strip club owners had kept the safe.

“The manager was murdered down here,” Ciarán said. “Shot right in the head.”

“Grim,” I said. He touched my hand and asked what had happened to my fingernail, which was black and half-falling-off from trying to smash my phone and accidentally smashing my finger instead. I considered telling him a lie, but it was too difficult to think of one, so I told him the truth.

“Why would you do that?” he asked.

“I was back home,” I said, as if that explained it. Which it kind of did, because then he started asking me about my hometown, and I told him about moving back in with my parents after my ex had kicked me out of his apartment and called the cops on me for texting him too many times. Ciarán seemed interested in all of this, like he didn’t judge me for being a fuck-up and might not judge me for this being my only job. Then he asked how old I was, and when I told him twenty-eight he couldn’t believe it. He said I looked eighteen or maybe twenty, and I realized I should have lied.

Ciarán led me down a hallway where a fan was dripping water onto the floor, then down another hallway to the fridge. I found Jamie’s crate of condiments and Ciarán retrieved his, which someone had vandalized to read “Queeran” instead of his name.

He said that one day I would get a condiment kit of my own.

“I can only dream,” I said.

“Dream bigger.”

Upstairs, Jamie and I went through the list to make sure we hadn’t missed anything, and realized we’d almost forgotten the water. I held a five-gallon plastic bottle under the tap, spraying water over my face and shirt in the process. I took the water out to the van and when I came back, the red meat was ready to be put into the hot boxes. The hot boxes were heavy, and we slid them most of the way to the door before carrying them down the stairs. I grit my teeth, lifting from my back in a way that I knew would hurt later.

When we heaved the hot boxes into the van, Jamie told me I was stronger than I looked, that she’d been worried for a minute. My fingernail stung, but I felt proud that I hadn’t let her down.

I got in the van and Ciarán called out goodbye before he left with another Irish guy named Sean. They were going to cater a vampire movie in New Jersey. The others were catering a commercial for a mattress company, a children’s show about ponies, another vampire movie and a competitive barbecuing reality TV show. I was disappointed we weren’t catering a feature film or something with recognizable actors. We were driving to a production office, which Jamie warned me was where dreams went to die.

We arrived at a nondescript building and were led to a tiny room where we somehow had to fit the ten chafing dishes on two folding tables.

“I’m not setting up the salad bar,” Jamie said, putting out only metal bowls of plain spinach and Caesar salad. “There’s no fucking space.”

I started using my fingers to pry apart two chafing dishes that were stuck together with encrusted meat and banged my busted nail, which started to bleed. As I swore and my eyes teared up, I saw that Jamie was using a metal serving spoon to pry apart the dishes more easily. I went to the bathroom to wrap a piece of toilet paper around my finger and then put on blue latex gloves. By the time I came back, Jamie had finished setting up. We poured water into the chafing dishes and lit the fuel cans to heat them up. While we waited for the water to start steaming I watched a dark stain of blood pooling inside my glove.

When the room became humid, it was time to remove the trays of food from the hot boxes. The broccoli was cold to the touch, and pork grease had spilled all over the inside of a hot box. The tofu was grey in colour. The rice looked like it had been vacuum-sealed. We heaved the pork into a chafing dish, and the smell made me gag as some of the fat dripped onto my Nikes, which were warped from my parents’ washing machine. There was no room for the grilled chicken or the rice, so Jamie said fuck it and left them in the hot boxes.

Even though it wasn’t twelve yet people started coming in, saying things like, “Mmm, that smells delicious!” or “Something smells good!”

Jamie volunteered to carve the roast, and I stood in the middle of the room as everyone loaded up their plates. Someone asked if the potato wedges were gluten-free, and before I could find the allergens sheet, Jamie responded that they were. A group of men made disparaging comments about the tofu and I fake-laughed in response. An older blonde lady asked if we had balsamic vinegar and olive oil, and I checked Jamie’s condiment kit even though I knew we didn’t. When I told the woman, she dumped her spinach in the garbage bin in front of me. Someone asked why there wasn’t any rice and I said nothing.

I went to the bathroom to replace the toilet paper wrapped around my finger, the blood dripping into the toilet. When I came back the room smelled even worse, but some of the employees had started coming back for seconds, piling leftovers into Styrofoam containers or Tupperware that had been brought from home. Jamie had finished carving the pork and said we could probably eat. She went through the line loading up her plate, but all I took were some potato wedges. We stood eating in the hallway as a woman went into the room with empty yogurt and sour cream containers, filling them with leftover tofu and broccoli. She put the containers in a shopping bag and scurried upstairs, and moments later came back down with a plastic water pitcher that she spooned slices of pork and juice from the roast into.

In the weeks that followed, I carved still-bleeding steak for child actors on a pony farm upstate. I worked a Pepsi commercial with an aspiring comedian who wouldn’t stop talking while I tried to read on my phone. I sent my mother pictures of actors in graduation gowns, and she asked if I was still considering grad school. One day I set up in a hospital basement with a Greek guy who carried everything for me and took my side when Paddy reprimanded me for being on my phone. The film set’s generator operator told us the lunchroom used to be a morgue, and pointed out the rectangles on the floor where the beds had once been bolted.

Another day I went to do one of the vampire movies with Tara, who on the hour-long drive out of the city told me stories about smuggling her sister’s boyfriend over the border after he got deported for overstaying his visa. I never worked with Ciarán because neither of us could drive. I started bringing Tupperware to work, filling my fridge with containers of soup and Ziplocs of soon-expiring organic spring mix. I showed up one day to discover my name had at some point been moved from the list of part-time employees to full-time.

I was on a Tinder date one night when I got a text from Jamie that she was drinking with the Irish guys from work and they were asking about me. I left my date, saying I had to teach for TutorWow! at 5 AM, which hadn’t been true for months, and met them at a dive bar in Bushwick. At first I sat on the other side of the table from Ciarán, but as the night went on and we drank more Jameson, everyone else left and I was soon sitting beside him calling him a dick. He asked me what he had done to make him a dick and I told him I’d forgotten.

“Exactly,” he said.

He came over and we had unsatisfying drunk sex. I had to remind him to wear a condom, but he held me all night with unexpected tenderness. Only later did I remember that what had made him a dick was his asking Jamie why she was always such a bitch.

At work on Monday, Ciarán came over to say hi while I was polishing the cutlery. It felt exciting that no one knew we had hooked up except Jamie and Sean, and Tara, who I was paired with for the day. She asked me about it on the drive to the vampire movie shoot, before launching into a saga about the time she went to jail after taking the fall for an ex-boyfriend who had been selling pills out of their apartment. He would have been deported otherwise, and she’d been young and in love, she said. I couldn’t tell if she meant the story to be a romantic or cautionary tale, and either possibility disturbed me.

When my smashed fingernail was finally beginning to grow back, Paddy asked me to work a Vans skateboarding event—a rare weekend shift—and I agreed because I thought I might get free shoes. I was excited when, a few days later, Ciarán’s name appeared on the calendar next to mine for the Saturday. We were supposed to make waffles at the event. Paddy asked if I’d ever used an industrial waffle maker before, explaining it wasn’t as easy as it looked.

“I’ll watch a YouTube video,” I said.

Fantasizing about the event got me through the week of Paddy giving me a hard time about being on my phone, and the salad guy yelling at me for grabbing extra bowls off the shelf behind him. It got me through falling while carrying the cutlery bucket, scattering forks and knives on the floor as everyone clapped. It got me through the calluses on my hands and the lower back pain and spilling more food-runoff juice from the hot boxes on my Nikes, which had become unwearable outside of work. It got me through my clothes and backpack smelling like grease and the sarcastic comments from gaffers about the tofu, and through the texts from my mother with links to teaching jobs and questions about when I was going to visit home.

The night before the Vans event, Ciarán liked my Instagram post at 3 AM and I felt a rush of excitement that he was thinking of me. But when I showed up at the skate park the next morning, Ciarán wasn’t there. Instead, Paddy’s nephew, who usually ran the taco truck, said he’d help me set up.

“Where’s Ciarán?” I asked Paddy, who was unloading the van. “I thought we were supposed to work together.”

“Ciarán’s dad had a heart attack and he went back to Ireland last night,” he said, placing a box of waffle mix in my arms.

Paddy had to drive back to the kitchen before we could get the waffle iron working, and despite my extensive YouTube research, I couldn’t figure out how to operate the machine, dripping waffle batter all over my newly acquired free hoodie and shoes. Someone from Vans thought the problem was that we hadn’t seasoned the waffle iron first. Paddy’s nephew said the temperature was too high, while one of the skater moms thought it was too low. I chopped bananas and strawberries, trying to pretend that I wasn’t involved with the event even though the back of my hoodie read “FRIENDS AND FAMILY” underneath the Vans logo.

Eventually I handed out paper bowls and turned the waffle bar into a candy bar, the kids covering their bananas with sprinkles, Nutella and whipped cream. No one seemed to mind that there weren’t any waffles. When I texted Ciarán how sorry I was about his dad, he responded right away, saying he appreciated it.

Work was unfulfilling without the possibility of seeing Ciarán, and Jamie had finally gotten a PA job on the set of an indie film.

Congrats, I texted her. Now you’ll be the one complaining about the food!

Tara started dropping me off at small production offices where I had no one to talk to throughout the day. I read on my phone at work more and more, mostly e-books from the library, catching up on the James Joyce and Samuel Beckett I’d missed out on by majoring in film instead of literature.

I didn’t want to make my own condiment kit, so I kept using random ones from the fridge even though they never had balsamic vinegar or olive oil for the older blonde ladies. I started staring back blankly when the production managers complained to me. One day when Paddy drove me to a studio I got us lost, even though I had been there the day before. The next day, a guy named Jesse picked me up and we got lost going back to the kitchen. He ended up driving me around his old neighbourhood, showing me his high school and the house where he grew up. I worried he was kidnapping me until I realized he was just stoned.

One morning Sean told me that Ciarán’s dad had died the night before. I texted Ciarán to tell him how sorry I was, but he didn’t reply.

That day, I had to help Tara set up for a room of bagpipe players rehearsing Christmas carols. It depressed me that over a hundred people were working twelve-hour shifts to make a Netflix Christmas special no one would watch, that one guy’s entire job was guarding a door all day and another’s consisted of placing pink pylons down a set of stairs leading to the lunchroom. My job was the most depressing of all because I was responsible for feeding the people who did all the other useless jobs.

Later, Paddy announced that Ciarán would be coming back the same week that Sean was leaving, so there was going to be a joint going-away/coming-back party.

When I arrived at the bar for the party it was just me and Tara and Sean and the aspiring comedian. I was already tipsy from drinking boxed wine at home, and ordered the strongest IPA on the menu. I reapplied my lipstick in the bathroom and started talking to Sean about James Joyce, how I wanted to visit Ireland one day just to see the places Joyce described in Dubliners. Sean told me he’d once been mugged right beside the James Joyce statue. “I hate that fucking statue.”

Paddy arrived and said that the next round was on him, but really the whole rest of the night was. I ordered a Guinness and more people from work arrived. When Ciarán showed up he gave Paddy a hug, and then he hugged Sean, Jamie and finally me, our hug lasting longer than the others.

We did shots of Jameson on Paddy’s tab and got even more drunk. Around midnight I began to feel sick and decided I needed to leave immediately. I disappeared without saying goodbye to anyone. I walked to the bus stop, but when I arrived the bus passed by without stopping. I didn’t know when the next one was coming, and decided to walk to the subway.

I concentrated on putting one foot in front of the other and ignored the taxi drivers slowing down beside me every few minutes and rolling down their windows. In my head, I gave myself a pep talk.

You can do this, I told myself. I’m really proud of you. Keep it up.

Usually my inner voice told me I was a fuck-up, so it was nice to hear some positive affirmation for once. I marvelled at myself for holding it together.

I’m such a champ, I told myself. I had never used the word “champ” before, and decided I needed to introduce it into my lexicon. When I caught the train I grinned at the other passengers and called them all champs in my head. It took me a few stops to realize I’d taken the wrong train and was on my way to Queens. I sent my mother a crying face emoji, and when she didn’t reply, texted Jamie that I was lost on the subway but that I was giving myself a pep talk.

Good job, she told me. You’re your own mom now.

This idea gave me the strength to ignore the other voices in my head calling me a fuck-up and to talk to myself like a supportive mother would. Everyone makes mistakes, I told myself. You just have to follow the platform around the other way. It’s an easy thing and you can do it.

By the time I made it home, Ciarán was calling me from Sean’s phone asking where I was.

“I had to leave,” I told him. “Come over.”

I woke up an hour later to five missed calls, eight missed Facebook calls and an urgent message: Wake up!!! When I called back, Ciarán picked up immediately.

I gave him my address and he said he was taking a cab. His desperation was endearing, and we had sweet and gentle sex that made neither of us come.

When he woke in the morning, he rolled over and lay on his stomach, propping himself up on his forearms. His eyes were still closed, and he was breathing heavily. I was watching him remember that his father was dead, I realized. For the foreseeable future he would have to wake up every morning and repeat this until it finally sunk in that his father was gone. I stroked his back, comforting him, trying to be his mom, too.

“Are you okay?” I asked.

“Just have to take it one day at a time,” he said in a muffled voice.

“I wish I could help you,” I said, playing with his hair.

“Just something I have to go through on my own,” he said. “All of us do.”

I was struck both by the gravity of his statement, and by my own naivety. I knew I had been forgetting something all this time, that the catering job was only a distraction from the grief that awaited me. Ciarán had moved into a room of mourning, leaving me outside. One day I would enter it—sooner than expected, as my mother would die of a heart attack just a few years later—but for now it remained foggy, just out of reach.

He dressed and left, and we made no plans to meet again outside of work. I texted him every two days afterward asking how he was doing, then decreased the frequency to every three or four days, and then every week.

Every time I wrote he told me he was taking it one day at a time, and every time he saw me polishing cutlery he came over to say hello. I asked for more and more days off, and Paddy scheduled me for fewer and fewer shifts. Soon my name moved from the list of full-time employees back to part-time, where it remained until I lied and said that I had gotten another job. ⁂

Cassidy McFadzean is the author of three books of poetry. Her fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in Joyland, the Walrus, Hazlitt, and the collection Dead Writers (Invisible, 2025).