Collage: Nancy Pavan; photo: Amin Yarban, Unsplash.

Collage: Nancy Pavan; photo: Amin Yarban, Unsplash.

The Drowned Valley

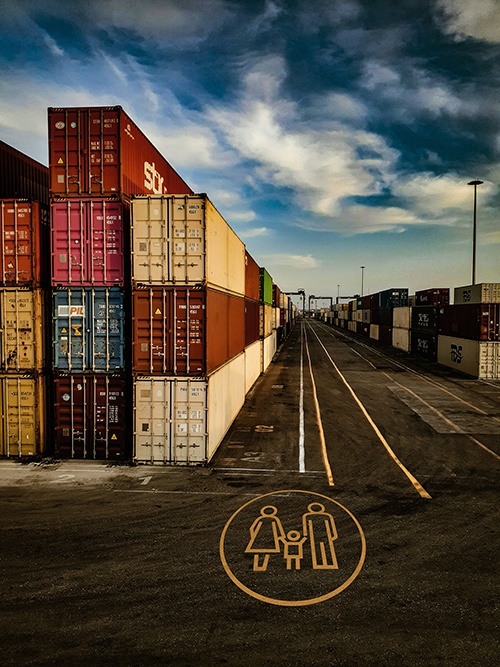

There was a man who had a perfect tarnished wife and whose job was to drive around in circles. Whose job was to follow his orders, moving containers around the port, from Zebra to Bobby to Apple, never knowing what was inside them. The containers were rust-red and clay-brown, refrigerated or unrefrigerated, and it was not his job to know what was being shipped or where. Sometimes on sunny days he would open his machine’s windows, and if he happened to be eating from a bag of Cheetos he would flirt one out the window until a crow gusted down, pawed onto his window sill and daintily sniped from his hand that orange mystery.

The man’s workplace was full of characters—all you needed was your GED to get on the cardboard, and there were more than a few guys who’d done stints in Colchester. The man would mostly try to ignore the Ivermectin knuckleheads and the Fuck Trudeau guys who’d recently changed into Fuck Trump guys. But there were plenty who weren’t so bad, just plain steady guys like him, like his father, the union steward, who knew all about the containerization revolution and who said this was the last good work and now the machines were trying to take it, but machines didn’t pay taxes now did they?

Much as work could be tedious, the man’s main problem was at home, where he and his wife had taken quite a blow of late. Sometimes the man thought his wife was perhaps a genius. Like for example the time she pointed out that we only say “so and so is a force” when referring to women? Janine is a force, Michelle Obama is a force. Which—had he taken the meaning right?—meant that, in the eyes of society, a man was never “a force.” Said man was soft and likeable or he was a hard powerful asshole. Or possibly it never needed to be stated if a man was “a force?” Either way: profound. Further evidence of her genius: when they played Boggle, she routinely doubled his score. When she came home from work, she wore a little moustache of VapoRub under her nose to ward off the smells of the men who had “fallen” on plungers and kitchen implements, which then had to be surgically removed.

The thing is, there was a lack in their life. A lack that could be measured in boxes. Among the boxes—it is painful to tell this part—were certain IKEA items that had never been opened. Like a fish-themed mobile, carefully picked out. Like Honest Company boxes, as well as items from the barbecue party they had held, where their parents had walked around asking for the Wi-Fi code, the gifted diapers piled in a great ziggurat on the deck. There was no manual for the questions they’d had to answer in the end. Questions like: should there be a christening or any other ceremony? Questions like: how would they prefer to dispose of the remains?

The man was proud of his modest ambitions—all he wanted was to make his wife happy, but, after what they’d been through, that had become challenging. The hardest thing was seeing her withdraw: this woman who had once been a karaoke triumph, an archangel singing “Malibu,” her face a radiant Courtney sneer. This woman who had driven from Cape Breton with nothing in her trunk but a stand mixer and a pair of red velvet stilettos. Now she was at home, but she was not at home.

He thought sometimes of the Before. How his wife had liked to point out that, although he did not have a hairy bum, cheekwise, he had a patch of hair that sort of sprouted out of his rift area? And she was sympathetic to this? Even liked it a little? Not as in liked going there, but liked it in the sense that she used to call it “la moustache” and sometimes pinch and wiggle it to surprise him as he flamingoed his underwear on. Once, he and his wife put baby powder on their butts before farting, just to see, don’t tell anyone, seriously, she would be so humiliated. Another time, she asked him whether he would rather have his head or his whole body frozen, cryogenically speaking. These were things he held on to now. Things he hoped would come back, if not in precise recurrence, then in spirit.

Sometimes, on quiet nights, he went into the garage alone and sat among the boxes, pondering the mobile they had picked out: sky-blue with little fish that swivelled as it turned. In those moments he longed incomprehensibly to watch that mobile spin, as they had watched the demo version rotate in the store, only this time he imagined himself as an infant, reaching up in babbling curiosity toward the blue fish floating above in dreamy procession.

The man had not been sleeping well. Had, in fact, been prescribed medicine for his sleeplessness, likely caused by shift work plus stress plus grief. The union wages encouraged him to work long hours, often twenty-four straight. If he worked twenty-four hours on a Sunday, he would be paid triple-time for sixteen of them, a routine that was common practice at the terminal.

There had also been an incident. Of course, with all those containers and all those machines moving around in a confined space, there were regular accidents. Once, he had witnessed the cord in the gantry electrical room, a hundred metres above the pier, wrap itself around a worker and pull him tight against the wall of the room, the victim pinned scrambling and breathless, inches away from tumbling through a 4 x 6 feet cavity, his colleagues finally sprinting up to slice him free. The incident in question was much less severe: the man, operating the yard tractor, had put a container down too forcefully onto the stack in Zebra. No one was harmed, and the container did not fall, but there had been a bright metallic keen, as well as a clang that had carried through the park and down past the hot room, where the white-hats and the foremen lurked.

For this transgression he had been ferried to Dartmouth, where a woman in a lab coat had instructed him to urinate. Later, his supervisor had driven him back over the bridge, and as he looked out at the shipyard and the Bedford Basin and the seven cranes of his terminal, he’d recalled a thing his father had told him once: that a harbour is a drowned valley. That down at the bottom, beneath the deepest natural harbour in the world, there was a whole other realm, the undersea memory of a lush green plenitude where mastodons and sabre-toothed cats and giant sloths had once loafed and thrashed and fed.

At home, he’d nestled in beside her. She smelled of VapoRub and half-forgotten dread.

I pissed hot. Out for a week.

What were you on?

Nothing.

Nothing?

Just my medicine.

Your medicine.

No word of a lie.

The event happened months later, and in the interim the man had developed more control over his sleep. He was walking more, in the forest by his workplace, and putting the phone in another room at night. He was well-rested that day, so insomnia was not at play. The man had no other reason to question the veracity of the event.

It was Christmas time, and he had been watching timid snowflakes perish in the waves. On the rocks, which could be slippery, the words NO CHILDREN were printed in crude yellow spray-paint. The job was a pale monotony that night, and at around 2 AM the man was in line with the other yard tractors, waiting to load up farming machines from the ship, which was probably the Wren or the Jay or the Tern. In his boredom, the man entertained his habitual fantasy of operating the crane, the big gantry crane high up above the pier where he hoped one day to sit. The crane stood at the edge of the pier overlooking the sea, the sea that became increasingly monstrous, ravenous and dark when you worked next to it all day. Still, the man dreamt boyish dreams of perching high above that sea, dangling the containers from the ship into their piles, swinging them tenderly, with utmost care.

The unit was assigned the task of hitching the yard tractors to a fleet of fifty Komatsus and then driving them off the ship, past the garage and over to the transport trucks. Which meant waiting for the drivers to get them up and chain them to their rigs, and it was not his tractor but the one in front where he saw the hair drop down. A hand reaching for buckles. A small hand, like a doll’s.

The world went still, floaty. All the lights went sort of blue, then green, then deep orange, then back to bright white. The man knew he should have gotten straight on the radio, but instead he began to look left and right. His vehicle was behind a stack of refrigerated containers, so it was really only the one guy in front and the one behind who could see, and they were both zombie-ing down at their phones. So he hunch-walked up to the tractor and said, Hey. Woah, where’d you come from.

The boy looked up. Black hair, brown eyes. Grey sweatpants and a loose-fitting Harvard sweater. White running shoes, not a brand the man recognized. The boy’s clothes, skin and hair were neat and clean.

The man told him just hold on, and he unscrewed the cinch, peeled off the chains (chains!), pulled the boy out by the shoulders, his legs dragging limp.

There are decisions that we make, and there are those that seem to be made for us. There are things that are given, that present themselves.

Quickly, the man scanned the other tractors and saw that there was nothing tied to the bottoms. Before he really realized what he was planning, it occurred to him that it was a good thing it was dark out, that the whole thing would have been messier in the day.

The man carried the boy up to the vehicle, felt the child’s slight ribs against his own. The boy was maybe five, maybe seven, and his eyes were up in the sky, staring at the gantry haze and the diminished stars and the slow yo-yo of crane #4 lifting a forty-foot box. As the man gentled him up into shotgun, he waited for his heart to start juddering, but it remained strangely still, flushed with a calm that felt good and true and right. He felt the thrill that it was to act, to take control.

The man patted around, found a half-eaten sleeve of trail mix and a stale chocolate Timbit. The boy shook his head, pointed to the ocean. The man handed over his water bottle and the boy opened it and stared a long time into the dark cavity of the mouth hole. Then he drank the entire contents in slow, measured sips. Only then did the boy pour a few nuts into his open palm and offer them his mute inspections.

The man took a breath. Over the narrows, the night was already paling. This was wrong, yet it could not be, because it was perfect. The man was protecting a child.

The boy chewed, still staring at the sky. Twenty minutes until break.

Parents? the man asked.

The boy avoided his eyes.

Family?

The boy seemed not to understand.

Mother?

He remained still.

Father? Papa?

Frustrated, the boy shook his head, but the man did not know if he had been understood. The boy poured the rest of the trail mix into his mouth and chewed, hardly swallowing. He made a little bow that might have meant thank you. The man called dispatch and told them family emergency, someone was going to have to deal with yard tractor #214. He got the boy into his truck and headed through the gates, down onto Marginal Road. Up Quinpool, a soft dawn crawling over the Northwest Arm.

As they passed over the bridge, the man told the boy about the drowned valley, walked him through what that would have looked like. The trees gone swampy, ankled in lily-pad brine, the shores slowly turning wetland and then swallowed altogether by the grey indifference of the sea. And then he told it the other way: the sea shrinking away, the whole peninsula growing as the beaches receded. The valley drying, the wet rocks slowly undrowning, all the water sucking out and the grasses sprouting tall, living and dying and turning soil, and then the flowers rising all at once, lupins and lilies and hyacinths. He did not know how much of it the boy understood, but he could feel that the boy was more comfortable when he spoke.

The man’s wife was still at the hospital. He showed the boy the guest bedroom, then the bathroom. He boiled water for instant soup. When he came back into the living room the boy was gone. The man searched the basement and the yard and the guest room, found him sleeping in the main bedroom in his Harvard sweater. Clutching the sheets, the cat kneading the covers around the pillow.

The man heard his wife’s car whir up and park. Sitting at the table, he shifted the bowls around, nervously pulled the spoon from the soup.

She leaned on the counter, eyed the two bowls on the table. What’s this?

I don’t know what to say.

What do you mean?

I can’t explain it.

Explain what? What are you saying?

He didn’t speak.

Who?

He hasn’t said anything.

Who?

The man took her to the bedroom door, showed her the boy asleep in their bed. He watched her close, monitored her, thinking of all the things he could lose, all at once.

Found him on the yard. Tied to a tractor. I asked about his family but he didn’t seem to have any, not here or whatever. Or he didn’t understand. I didn’t know what to do. I don’t. Somehow it seemed—. I mean, we’re trustworthy people?

No family?

None.

Is there, like, a policy?

I don’t know. Not that I know of. We tell the checkers I guess.

But you didn’t—

Tell? No. I thought—I don’t know.

We should call someone, tell someone.

Yeah. No. Of course. We will. Like now?

Yes, now. I don’t know.

Light frothed into the window. The man stared into the nautical chart on the wall, all the coves connected by the swinging line, the coast itself the shape of a wave.

But where would he go?

The right place? To be processed?

Processed. Yeah, of course. It’s just—

It’s fine, she said, slumping onto the edge of the bed.

She lay there with him, near him, and the man felt her energy change, a new rhythm come into her breathing. Or maybe an old rhythm? A rhythm he’d almost forgotten. The man waited for her to say something, tried to think what else he might say.

He made her a peppermint tea and brought it in, set it on the nightstand and continued sitting, not touching anything. Outside, trucks rumbled down their street and the jackhammers started to pound and the boy slept through it all.

The man went into the living room and lay on the couch thinking of boxes, of boys, of tractors. Then the ocean, waves coming in, accumulating, slowly drowning a tired valley of green.

It went well the next day. Surprisingly well. The man declined his orders. His wife called in sick, went to the store for a booster seat and colouring supplies, picture books and several boxes of LEGOs. The boy ate and drank and played all day with the new toys. She turned on Raffi and the boy bobbed his head to “Baby Beluga.” That evening, she bathed the boy. The man sat outside the door, his phone face-down in the other room. He flipped through a magazine. And then he heard it. He was shocked at first, and he feared for her. This was how long it had been since he’d heard the sounds of her laughter. He wondered. He imagined her face. He thought about opening the door, but decided to continue preserving the boy’s privacy.

When they came out together, the boy was wrapped in a towel. The woman was holding his hand, and they were both smiling timidly. They read stories and then all three of them slept with their clothes on in the perfect, purring dark.

In the morning there were messages on the man’s phone. He ignored them. They built more LEGOs. The boy made an enormous tower of red blocks, almost as high as his head. There was a white speedboat, on which he built a kind of Stonehenge. The man remembered how he had loved blocks as a child, and wondered if this was not universal. Was there something about rectangles? Something about containers?

Then came the knock on the door. The boy had been sitting at the window, flipping through the LEGO instruction booklet. Smiling, calm as he could manage, the man stood and closed the curtains. He put his finger over his mouth, as in quiet. He locked eyes with the boy, who seemed to be afraid. In this moment, he felt certain that the boy would commence just then to speak, perhaps to shout, or scream. Which made the whole thing seem suddenly more severe than he’d realized.

He pulled the curtains back and saw his colleague, Dale, standing there. He looked at his phone. U okay?

He showed his wife the message. She looked at him like, It would be dumb not to write back.

Fine, he wrote. Just hopped out of the shower.

Work said something about leave? An emergency?

Nothing too serious. We’ve had a rough go.

Course. Anything I can do?

They watched, cautiously, as Dale climbed into his truck and rolled slowly away, thumbing through his phone and peering in the rearview.

We should go, said the wife.

Okay. Where?

They settled on a place nearby. Glow Gardens. The wife had seen her cousin’s pictures. Neither of them had been there before, so they were surprised by the crowds, and the arcade. They walked through the enormous warehouse past lobsterish spray-tanned men in blazers and V-neck T-shirts paying ludicrous fees for coat check. There were lanes of string lights arranged into hearts, fairy lights in the shape of enormous rectangular picture frames, would-be models posing grinningly within. There were pulsing tunnels of red-and-white lights, children scampering through; Christmas trees and white LED snowmen, six-foot phosphorescent candy canes; stacks of ribboned presents, pulsing ethereal. At each display there was a platform for photographs, beside which a sign read AS A COURTESY TO OTHER GUESTS, PLEASE BE MINDFUL OF YOUR TIME WHEN TAKING PHOTOS.

The boy roamed about happily, a gentle smile on his face. The man felt unsafe and unwell, looking about at the men with trimmed beards, the filled and contoured women holding light rings like battleaxes, children sword-fighting with selfie sticks, the sallow Ozempic-drained faces of the forever young.

And then he was gone. What had happened? The man’s heart gone paralytic thunder.

Where is he?

I don’t know?

You lost him?

Me?

I was in the bathroom. I said.

Oh fuck. Oh shit. The man scanned the children. Do we move or do we stay? They had no plan. He remembered that his father’d had a special whistle for just such moments. Whee-whe-whe-whoo. A safety measure. Uselessly, he tried this whistle. He looked for the boy’s Harvard sweater, which he had laundered yesterday. He looked for the white running shoes. He ran into a forest of icicles, beside which an Elsa impersonator, whose brown sideburns showed beneath her blond wig, belted a frail and tremulous version of “Let it Go.”

He was lost in this children’s world, this tortured paradise.

And then he saw Dale. Dale locking eyes. The wife saying, Shit, fuck, it’s Dale, what the fuck? The man glimpsing the authorities, some in uniform, some in plain clothes. No boy though. The boy, presumably, already taken.

There was some shouting. In the man’s view, too much. It was not needed. Words like “deranged” and “psycho” and “a god-damn child.” The word “fugitive” might have been used. The man did not resist. He did not think it so terrible, what he had done. Not so very terrible.

As they were escorted away from that pit of light, might he look over at his wife, perfect and beaten and still so hale and lithe and strong? Might he mention his feeling that they would likely not see each other again for some time? The lights on her face perhaps blue and white, the cavern of Glow Gardens behind her, perhaps she would say that it was okay, it was alright, the boy would be alright, was always going to be alright. Somehow she was sure of it. And maybe as she said it, the man would know it was true. Maybe he would remember how the sound of his speaking voice had seemed to ease the boy. And he would think how he would have liked to take the boy up with him into the crane, to show him how it looked different, the sunrise, from way up there. When the first tease of sun comes over the Eastern Shore, the trees on the hills gone golden, a thousand pine trees limned in light, a fleet of speechless angels. ⁂

David Huebert is the author of Oil People (McClelland & Stewart, 2024), shortlisted for the Amazon Canada First Novel Award and the Thomas Raddall Atlantic Fiction Award.