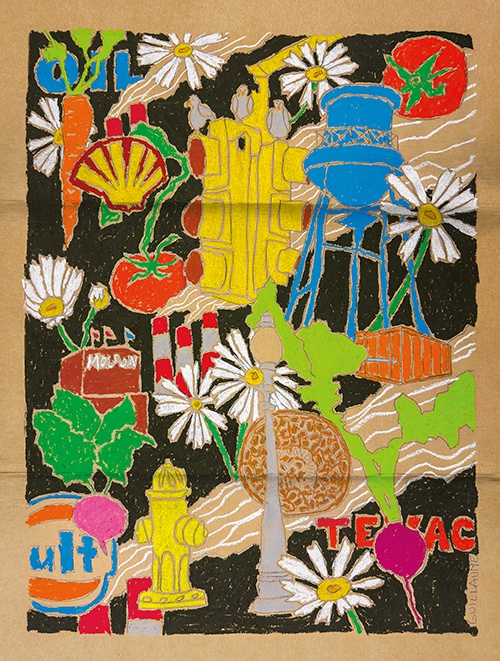

Art by Guillaume Brière.

Art by Guillaume Brière.

Making Montréal-Est

The history of this small city is intertwined with heavy industry, as are the plans for its revitalization.

A sulfur processing plant. An oil refinery. A chemical warehouse. Corrals of shipping containers. A depot for petroleum coke, a by-product of oil refining. Oil tank cars lined up along the street in a long row. Manufacturing centres, factories and the carcass of a building still bearing the marks of an old fire. The site of a soon-to-be-constructed airport fuel storage terminal along the northern bank of the Saint-Laurent River. These are the landscapes of Montréal-Est, a city on the eastern end of the Island of Montreal. The lines of division between it and Montreal are as olfactory as they are carved by CN rails: base and acrid, the dense warmth of gasoline and the cold musk of cement, dust and exhaust.

Stretching between the Montreal boroughs of Anjou in the west and Pointe-aux-Trembles in the east, and home to fewer than five thousand residents, this is a city unlike any other. It was built almost entirely on the back of the oil industry, with residents considered an afterthought for decades. The city is now attempting to reinvent itself under the banner of urban revitalization. Its newest development plan refers to it as a “laboratory-city,” meant to harmonize residential, commercial and industrial interests and improve local quality of life. The plan transplants the mirage of Montreal’s sustainable urban planning onto industrial wasteland, promising mixed-use spaces, increased densification and industrial clean-up. But Montréal-Est, despite its closeness to Montreal, stands apart: far enough on the periphery to keep one from looking too closely at the significant ways it diverges from those visions.

Montréal-Est speaks in contrasts. As of 2016, the industrial sector made up almost ninety percent of its territory, while existing and in-development housing took up a modest ten percent, the remainder consisting of a few shops, playgrounds and a waterfront that tilts into the Saint-Laurent.

Life here is still modest. The 2021 census showed that the median total income for the city’s residents was around $39,000 per year. Avenue Broadway, the main artery running through the residential core, is a discordant mix of humble duplexes and small single-family homes, vacant and dishevelled commercial buildings, and warehouses turning their backs obstinately on residents. There are also scattered new builds of sleek triplexes and massive riverside condominium complexes, hinting at a redevelopment of Montréal-Est targeted at a financially comfortable demographic. The scarcity of people out on the street punctuates the self-contained isolation of this pocket of Quebec.

Montréal-Est can be considered “un quartier défavorisé,”—a disadvantaged neighbourhood— explains Peter Batos, director of Action Secours Vie d’Espoir, the only food bank in Montréal-Est. Founded in 1999, it is housed in a church on Avenue Marien, where the industrial and residential sectors bleed together. In that area, decrepit depots and numbered businesses behind high barbed wire lie below the chimneys of the nearby Suncor sulfur plant. Demand at the food bank, which covers both Montréal-Est and Pointe-aux-Trembles, has grown over the past two years, and the numbers tell a story of troubling changes all across the island. “I went from [giving out] 150 food baskets a week to 250 a week,” Batos says on a rainy day in March. Before 2023, there were usually around thirty weekly requests for emergency assistance, meaning those who hadn’t used the food bank previously or who were coming in last-minute due to something like an injury or a job loss. Now, the food bank has been seeing about seventy emergency requests per week.

The crisis of food insecurity emerging in Montréal-Est offers a glimpse of the deepening precarity looming over the region, despite the lofty revitalization plans that promise a harmonious future. “If I would open the valves and let it go, I would hit a thousand [baskets per week]. The demand is continuous,” Batos says. “I must have said no to over two thousand people over the last two years.” Every week, around fifty new requests can be refused due to lack of resources. Those refused either get a spot in rotation, waiting for the next available food basket, or don’t get anything at all. If they’re desperate, they might have to go to a food bank in Pointe-aux-Trembles.

To meet this increased demand, the food bank is currently increasing its capacity for food storage and preparation. Batos is also floating the possibility of lobbying for another food bank in the area. “Right now, one is not enough for this whole population,” he says. “You’d have a second food bank as big as ours open at the other end of Pointe-aux-Trembles, and it would be jam-packed every day also.”

The alarming need for food banks is reflective of problems throughout Greater Montreal, a region that includes Montréal-Est. According to charity Moisson Montréal, which delivers food donations across the island, in 2023 there was a 47 percent increase in the number of people receiving food assistance in Montreal. “There are those who come to our centres who are working, who have salaries, but don’t have enough money to meet their needs,” says Thierry Bachelier, director of the Réseau Alimentaire de l’Est de Montréal (RAEM), a non-profit focusing on food security in the region. The RAEM reports that one in three food banks across all of Greater Montreal has to refuse services to people in need. CityNews reported in January that requests for food aid across the province could rise by 10 percent over the next three years.

“In the east [of the island], it’s difficult to move around if you don’t have a vehicle. There are many inaccessible zones,” Bachelier adds. “This is why we call the east a food desert.” Besides gas stations, a small grocery store on Broadway is the only place to buy food in Montréal-Est. A big commercial chain is farther east in Pointe-aux-Trembles. For elderly residents, children and others who are unable to travel, a dépanneur might be their only option.

Outside a residence for people living with multiple sclerosis in the south of the city on Rue Notre-Dame, two men share a smoke. I ask them what they think about the future of Montréal-Est: have they seen any meaningful changes? They’re shy, but want to share. “We were born here,” one of them says in French. “The area used to be much nicer before, because where they’re building those blocks [of condos], it used to be nice little houses.” A sleek hockey arena across the street was renovated, but according to the two men, Montréal-Est youth who want to play hockey must typically travel to Pointe-aux-Trembles. For such a small community, every change is felt. “There’s nothing left in Montréal-Est,” his companion chimes in.

“It’s a city that could be rich,” Bachelier says, referring to the revenue that should be coming into Montréal-Est due to the presence of industry. Bachelier explains that many organizations, including the RAEM, receive government funding for specific projects, rather than regular payments to support their overarching missions, leaving them dependent on funding from corporations. “If we had a regular subsidy from the state, we wouldn’t need Valero,” he says, referring to the Texas-based energy corporation whose terminal and port infrastructure cross nearly the entirety of Montréal-Est. “It’s a necessary engagement because the state is not present.”

“Financially, the [food bank] is dependent on these big companies, right?” Batos says, explaining that with such a small population, it’s difficult to find money for local services. The majority of funding for Montréal-Est’s food bank comes from oil companies in the city, like Valero and Suncor, as well as other local corporate donors like the Glencore copper refinery. No oil money, no social services.

The busy throughway of Rue Sherbrooke Est demarcates the industrial sprawl of northern Montréal-Est from the south. It is as much an auditory divide as it is a territorial boundary. North of the street, a CN train pulls up under the shadow of the Suncor sulfur plant and rumbles to a stop, oddly silent in proximity to the droning traffic and transport trucks. The zone north of Sherbrooke is the heart of the city’s heavy industry—and the site of its most ambitious redevelopment plans. Reworking Montréal-Est’s relationship to industry isn’t going to be easy. Profound imprints have been made on this city by the oil industry, and the scars aren’t just skin-deep.

Montréal-Est was first founded by businessman Joseph Versailles in 1910; what was initially a small residential outpost saw the oil and gas industry bloom over the following years. Ever since Imperial Oil established the first refinery on the island in 1916, the story of Montréal-Est has been one shaped by the currents of global supply and demand. In the years to follow, two of the city’s mayors entered into politics through the oil sector, working for Imperial Oil and Shell. Texaco arrived in 1917. By 1939, the British American Oil Company, later Gulf Oil Canada, was also operating a refinery in Montréal-Est.

Dimitri Tsingakis, general director of the Association industrielle de l’Est de Montréal, an association of industrial companies in the region, says that Montréal-Est used to be “one of the most prominent industrial sectors in eastern Canada, and maybe in the whole of Canada.” This proud history, however, speaks more to the city’s past than it does to its current state, a shell of what it used to be.

Toward the end of the century, Quebec’s fossil fuel industry began to grind to a halt, the echoes of which are still being heard today. In 1982, unionized workers became outraged at Quebec’s importing of refined oil from Ontario through Texaco. They demanded the government nationalize a company as “Petro-Québec” to retain control over the local industry. The idea was never actualized. BP, Gulf, Imperial Oil and Texaco all shuttered their local plants during the eighties. The backbone of Montréal-Est was fractured. There are now two oil refineries left in all of Quebec: the Suncor refinery in Pointe-aux-Trembles, which has been operating since 1955, and the Valero plant in Lévis, across the river from Quebec City.

The industrial sector of Montréal-Est is in some ways a story of absence. Shell ceased local refining operations in 2010, converting the refinery into a storage terminal. The 2000s saw the closure of major heavy industry factories in the city, including Tuyaux Wolverine, a copper product manufacturer, in 2007, and Dow Chemical Canada’s Petromont polyethylene factory in 2009. La Presse reports that American shareholders weren’t happy with the Canadian dollar or with rising metal prices cutting into profit margins, and that hundreds of workers at the city’s plants, many of whom had worked in the sector for decades, lost their jobs. By 2010, approximately one in five households in Montréal-Est was surviving on less than $20,000 per year (just over $28,000 today). Last September, Montréal-Est’s Indorama, the only factory in Canada producing purified terephthalic acid, a chemical used in the production of polyester, closed its doors. The closure has left Canada wholly dependent on international sourcing.

Over the decades, the deep connection between the city’s residents and local industry diminished. Still, geographically, the industrial and residential areas of Montréal-Est are close together, and this proximity brings risks. “When you combine industrial activity and residential areas, you have to make sure there’s also land-use planning that comes into consideration,” Tsingakis says. “Anytime you put residential areas close to industrial sectors, you’re going to run into cohabitation issues.” In theory, there should be buffer zones, so that if there aren’t forests or fields, there are at least commercial blocks between heavy industry and homes. But on Avenue de Montréal-Est, just south of Sherbrooke, new builds are a stone’s throw away from a pipeline operated by Valero and the oil tank cars basking in golden-hour sunlight on the CN rails.

With proper maintenance and emergency response plans, Tsingakis doesn’t see the pipeline as hazardous. Plenty of people live near pipelines and gas lines. “We do like to think that we are good neighbours,” he says. “There haven’t been any industrial accidents that have caused [casualties] outside the industrial area.”

Public health research in the late nineties and early 2000s noted elevated cases of respiratory disease in Montréal-Est and neighbouring Pointe-aux-Trembles, identifying industrial activity as a potential factor in the phenomenon. More recently, the government of Greater Montreal reported that pipelines crossing the island and passing through Montréal-Est continue to pose a serious risk to drinking water for a significant part of the population.

Efforts to limit pollution have been contentious. According to La Presse, last May, American Iron & Metal, a metal recycling company in Montréal-Est, sought the annulment of a 2022 amendment of pollution regulations, claiming that the rules were unreasonable and useless. Last fall, the political party Québec Solidaire demanded accountability from the fossil fuel industry’s pollution in the province, citing companies’ downplaying of harm, negligence and environmental destruction. The party called on the government to sue oil company giants for their role in climate change.

In Montréal-Est, life right next door to polluting industry becomes banal. Yellow signs reading “Danger: crude oil underground pipelines” and warnings about the dangers of excavation mark unassuming driveways on Broadway. Local residents may have learned to live alongside heavy industry, but with more people in the city, there will be a risk of larger impacts from any potential accidents. More people is exactly what Montréal-Est has in mind, with the city’s Vision 2050 redevelopment strategy envisioning densification. An urban planning document from 2016 estimates residential areas being densified to roughly thirty-five to eighty-five residences per hectare of land.

Spring this year arrives in a tumult. Trump has launched a tariff war with Canada, impacting the cost of raw materials for industries from manufacturing to construction. The United States has withdrawn from the Paris Agreement and rescinded domestic environmental and industry regulations. These tensions form the backdrop for emerging development plans in the East Island, which includes Montréal-Est and the eastern boroughs of Montreal.

Hosted by the Chambre de Commerce de l’Est de Montréal, the Sommet de l’Est convention opened at the Olympic Stadium on April 7, bringing together politicians, corporations and community organizations to highlight initiatives in the East Island. The roll call of sponsors gives a portrait of the biggest stakeholders in the region’s development plans: CN Rail, the industrial waste management company Matrec and Suncor are just a few.

The convention presented a picture of urban development captured by big, flashy corporate funding. The 2025 event was the second edition of the convention, and saw announcements of over $1 billion in public and private investments. Small amounts of this funding were marked for the construction of a public park and a community centre, the redevelopment of a Franciscan convent, and organizations working with those experiencing homelessness; the largest investments, for private housing and industrial development, as well as the redevelopment of the Montreal Botanical Garden.

Quebec Minister of Tourism Caroline Proulx, in her speech at the convention, illustrated the dissonance between the development plans and people’s lived realities. She hailed the Olympic Stadium for its ability to host concerts, while the building was still plastered in stickers from a strike by roughly two hundred stadium workers demanding higher wages and protesting job insecurity; she invoked the importance of cultural tourism to the island by quoting Leonard Cohen in English, as the governing Coalition Avenir Québec party continues slashing minority-language services.

The issue of food security was relegated to the margins of the convention: upstairs, away from the policy-makers and the public. Presenters spoke on behalf of food banks from Rosemont and Saint-Michel in eastern Montreal, among others. In their talks, the emphasis on mutualisation—a tactic where collectives choose to share space and resources—pointed to a desperate flailing for survival amid deepening austerity.

The food banks were engaged in a game of realpolitik, prioritizing urgent practical concerns over moral convictions. During the conference, the term “corporate charity” was replaced with the more euphemistic “synergy.” Community organizations, aware of their deepening reliance on the private sector, tried to appeal to oil companies like Valero—notably present at the talk—in a bid to keep food in starving people’s fridges. The speakers didn’t talk about policies, or budgetary demands from the provincial or municipal governments. Desperate measures undertaken out of necessity became examples of ingenuity. The circular economy of waste reduction was celebrated: food that gets thrown out by grocery stores can end up with food banks.

Community gardens were lauded by presenters as a sign of sustainable development and democratization. By the CN rails in Montréal-Est near the border with Pointe-aux-Trembles, one such garden awaits the start of a new season. Last year, almost ninety percent of the over three tonnes of produce grown at the Valero-sponsored garden was given to food banks like Action Secours Vie d’Espoir for baskets. While such community infrastructure has concrete benefits, its dependence on corporate charity betrays a bandaging of social wounds. Down at the shoreline, the remnants of another community garden, abandoned since the pandemic, crumble out of the margins of Valero’s parking lot, crude oil coursing underground.

This spring, the federal government announced its own investment in the East Island, with $9.6 million in funding for projects contributing to “the economic transformation” of several eastern Montreal boroughs and Montréal-Est. The majority of this public funding is going to private companies—including cleaning product and metal companies, and the Chambre de commerce de l’Est de Montréal, a private-sector lobbying organization—with twenty-one non-profit organizations dividing up $1 million of additional funds.

Montréal-Est mayor Anne St-Laurent introduced the city’s Vision 2050 development plan this January, described in French as a “rare opportunity to radically rethink the development of a central city.” The plan has the redevelopment of brownfields—abandoned former industrial land—at its core. The vacant brownfields, vestiges of the city’s fossil fuel and chemical industries waiting for decontamination and construction, present “a veritable blank page,” according to Nicolas Dziasko, director of regional planning and economic development of Montréal-Est.

Redeveloping the formerly industrial land on either end of Montréal-Est will require cleaning up decades of pollution. Twenty-nine million square feet are set to be redeveloped, following the decontamination and purchase of the land. Two formerly industrial zones make up almost half of the land in Montréal-Est meant to be redeveloped, known as the A-40 Site and the Notre-Dame Site.

The A-40 Site, previously occupied by Dow Chemical Canada’s Petromont, is envisioned as a carbon-neutral industrial park known as 40NetZero. Billed as the largest sustainable industrial park in North America, the site will include between eight and twelve buildings. Construction materials that limit greenhouse gas emissions, light-reflecting white-painted roofs, solar-panel carports and parking lots made of recycled concrete back the site’s claim of carbon-neutrality. McKesson, a pharmaceutical giant, was announced this April as one of the first slated occupants. The majority of buildings are expected to be completed by 2027.

The second major brownfield redevelopment is the Notre-Dame Site, just south of the Glencore copper refinery and closer to Montréal-Est’s residential side. Sometimes, the provincial or municipal government buys back land while footing the remediation costs; other times, the government decides to subsidize clean-ups, like for the Notre-Dame Site. In 2023, Montréal-Est received a $20 million subsidy from the governments of Quebec and Montreal to support a five-year decontamination process. The cleaned site is slated to contain commercial buildings and a public park.

Near this abandoned plot, overlooking the Saint-Laurent River, a terminal that will store fuel for airplanes in Montreal, Ottawa and Toronto is under construction, the riverside already sprawling with fuel storage tanks. The Montreal-Trudeau airport has its fuel supplied by an underground pipeline from the Valero terminal; the new fuel terminal, built over two brownfield sites, is expected to have its own pipeline. Developed by the Montreal International Fuel Facilities Corporation, a consortium of airline companies, the terminal was green-lit in 2019.

For a decade, community members, including the mayor of Montréal-Est herself, have raised concerns about the terminal’s potential hazards. People have been concerned about increased pollution for nearby residents, as well as about the potential of accidents more catastrophic than the Lac-Mégantic tragedy, when a train carrying crude oil through the Estrie region in eastern Quebec derailed in 2013, killing dozens and destroying more than half of Lac-Mégantic’s downtown core. Some have also been worried about the environmental impacts of increased maritime traffic on the Saint-Laurent. Though these concerns were raised at public consultations and in a parliamentary petition, the project is going ahead anyway, with construction estimated to be complete next year.

At the same time, an expansion of public transit to the island’s underserved areas is being planned by provincial and municipal transportation agencies. The optimistic but ill-fated REM de l’Est, a light rail that was supposed to serve the East Island, was cancelled three years ago. This March, its replacement, the Tramway de l’Est, was announced. Sweeping from Montreal all the way out to the off-island suburb of Repentigny, the line will bring public transit to Montréal-Est.

Driven by Trump’s tariff war, Canada has doubled down on a rhetoric of self-sufficiency and the necessity of domestic industry. Fossil fuel transportation projects that had been shot down years ago, like the GNL Québec and the Energy East pipeline, have been brought up once more. Mere days after Carney’s election, a coalition of Canadian oil and gas moguls issued a demand for simplified regulations and increasing domestic production. At the provincial level, some Quebec politicians have been open to new pipelines through Quebec, while Bloc Québécois leader Yves-François Blanchet opposed turning the province into a “highway for dirty oil,” stressing that the dangers outweigh the benefits.

An example of the dangers of the proximity to industry unfolded last fall, when toxic fumes blanketed the neighbourhood of Mercier–Hochelaga–Maisonneuve, just west of Montréal-Est, as a shipping container with fifteen thousand kilograms of lithium batteries incinerated at a port. “As much as money can shut people up—to what point?” Batos says back at the food bank. “Are we going to develop more than just industry in Montréal-Est, to financially support the city?”

For over a century, the channels of the fossil fuel sector, maritime shipping and global capital have written the story of this tiny city with an idiosyncratic history. Even as Montréal-Est seeks to shake off the legacy of crude oil, its future continues to be shaped by the forces of industry. The plans for its new chapter are seeded among the rubble of citizens’ concerns and unanswered questions. The back-and-forth between residential, industrial and environmental interests takes on a rhythm as regular as the docking of ships at the port through the seasons. ⁂

Lital Khaikin is a journalist and author writing about the broad dimensions of conflict, including human rights, social movements and environmental issues.