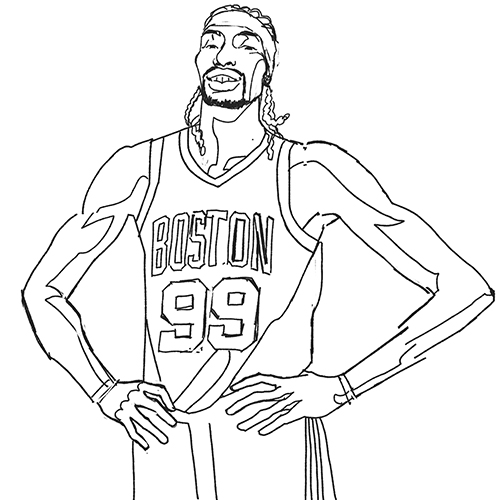

Photo by A. J. Schokora, Stocksy; Portrait illustrations by Franco Égalité

Photo by A. J. Schokora, Stocksy; Portrait illustrations by Franco Égalité

Home Court Heroes

Montreal has a record number of NBA players, but it’s been a long road to get here.

Sitting atop a dark grey Lamborghini convertible, Luguentz Dort sticks out from the crowd. People line the streets, craning for a view of the player who helped Montreal cement its new status as a basketball city. He’s returned to share glory with his community.

Dort is wearing black leather pants that stick to his legs in the mid-August heat, a black fitted cap and a sleeveless shirt declaring him an “NBA Champion” in screenprinted text. On the six-foot-four player’s lap sits the massive goldenNBA championship Larry O’Brien Trophy, which he occasionally raises above his head to get a rise from the fans who have come out today in Montreal-Nord, known to anglophones as Montreal North—a sight that Dort never thought he would witness. “At a young age, coming from here, I didn’t have a specific guy to look at, to be like, ‘I want to be like them,’ ” Dort tells the assembled media at the parade’s conclusion in Parc Saint-Laurent, where he started playing basketball as a kid. “It’s hard to make it to the NBA from this neighbourhood.”

Ever since the birth of the Montreal Canadiens in 1909—an original six NHL franchise that won twenty-four Stanley Cups behind mythical figures like Maurice “Rocket” Richard, Guy Lafleur and Ken Dryden—hockey has been ubiquitous in Quebec. The province’s identity is so tied up in hockey that many young kids dream about playing professionally when they are young, looking up to a litany of icons etched in Quebec history, their retired jerseys permanently hanging from Montreal’s Bell Centre rafters.

Dort is making history on a different path. Weeks after helping lead the Oklahoma City Thunder to the 2024-25 NBA Championship, he’s doing something exceedingly rare in professional sports but commonplace among his cohort of Montreal ballers: instead of spending his offseasons on vacation, Dort returns home to be among his people. In this case, he’s celebrating the completion of a milestone that a group of local basketball trailblazers have been hunting behind the scenes for more than fifty years—to bring a championship back home and give Montreal basketball the recognition it deserves.

More Quebecers are playing basketball than at any point in history. It’s the most popular school sport in the province, with more than forty thousand participants, along with a record 175 club teams competing in the Montreal Basketball League (MBL). Between 1983 and 2013, five Montreal-born players went to the NBA. Now, Montreal has five players in the NBA at once, two professional teams, a WNBA team—Toronto Tempo—coming to play two games in Montreal in 2026, and a host of young talent coming up next.

It took a long time to get here—perhaps longer than it needed to. Ever since the former McGill University teacher, James Naismith, invented basketball in 1891, there have been a myriad of forces holding Montreal basketball back.

In many ways, the genesis of Montreal basketball occurred far from the gated green hill of McGill University, in the historically-neglected neighbourhood of Little Burgundy, also known as Petite-Bourgogne. Southwest of downtown Montreal and bordering the Lachine Canal, Little Burgundy became the hub of the city’s English-speaking Black community after migrants came to work on the railway in the late nineteenth century. “If you were Black and in Montreal, and you were lucky enough to have a job, then you were working for the railway,” describes jazz pianist Oscar Peterson in the documentary, In the Key of Oscar. During the first half of the twentieth century, the “Harlem of the North,” as Little Burgundy came to be called, was a vibrant community made up of upwards of fourteen thousand people and 90 percent of Montreal’s Black residents, including a mix of Afro-descendents from the United States, the Caribbean, and the Maritimes who bonded over English in a predominantly French-speaking province.

The area fell on hard times following the Great Depression and World War II, when railway workers were being laid off en masse across the country. In the sixties, amidst burgeoning francophone political power, the city built the Ville-Marie Expressway through the historically Black anglophone neighbourhood, expropriating over a thousand households and displacing a significant portion of Little Burgundy’s Black community. The next hit came just months later, after the Lachine Canal closed for shipping purposes. Similar structural forces played out across the North American continent in that period, as infrastructure paved the way for thriving white suburbs and Black urban communities were dispossessed of resources. The Little Burgundy population dropped to less than seven thousand, with vacant land that once housed a mainly-minority community getting developed into housing for higher-income residents, 40 percent of whom arrived from outside of Montreal. “It was a place that was taboo,” Trevor Williams explains. “Everybody [said]: you stay away from Little Burgundy.” It became known as an area defined by poverty, drug use and street gangs.

Growing up in Little Burgundy, Williams looked towards athletics as a salve. “Sports was basically everything for me,” he says. “Kept me focused, kept me out of trouble.” After migrating from Saint Vincent and the Grenadines in the early 1970s, Williams and his nine siblings played everything from hockey to baseball, bonding with neighbours over their shared love of sport. “It was something that a part of our friendship was grounded on,” says Wayne Yearwood, whose parents immigrated from Barbados to Little Burgundy, where he met Williams. But unlike most kids in Montreal at the time, they gravitated towards basketball. “Basketball was definitely a place where I could sort of let my hair down,” Yearwood says, noting that it was the most affordable and accessible sport—still the case today. Plus, as a visible minority who was struggling to fit in alongside his predominantly white teammates in hockey, “basketball was an easier social environment to be involved in,” he adds. “There were more Black players that I could be close to that were more like me, that were from the same area as me and grew up the same way that I did.”

Eventually, an enterprising man named Bob White took notice. Born in Little Burgundy in 1935 to Jamaican immigrants Benjamin and Florence White, he was a highly skilled swimmer and one of the few Black members of the local YMCA’s swim and water polo teams. In the 1950s, he moved to New York City to serve as the aquatic director of the Harlem YMCA, where he was exposed to the civil rights movement. White returned to Montreal in the early 1970s and saw the lack of opportunity for his Little Burgundy neighbours, where about 64 percent of residents were below the poverty line, and police consistently harassed Black youths.He realized that sports could help the next generation of Black kids access scholarships to American universities that would provide free education along with room and board. Plus, White knew from his own time overseas that there were more opportunities to form connections and gain knowledge in big American cities than in Montreal, especially for English-speakers. So, he started the Westend Sports Association (WSA) in 1974 with a handful of basketball protégés, including Williams and Yearwood. “We were kids, man, eleven, twelve, years old,” Williams says. “And this guy is just walking down the hood, and he’s bringing records for us […] he was inspiring.”

White directed the boys across the border to an elite basketball camp in Honesdale, Pennsylvania. “There were courts as far as the eye could see,” Yearwood recalls. They woke up to the sound of loudspeakers at six in the morning to eat a breakfast buffet on long picnic tables before competing against the best American players, in front of rows of NCAA coaches. Williams and Yearwood would go on to land NCAA scholarships and play for Team Canada. Yearwood would even play at the Olympics in 1988. “Through [White] I realized I could attend school for playing this game,” Yearwood told the Montreal Gazette in 2016, upon White’s death.

By moving to the US and taking advantage of its well-built, sophisticated basketball infrastructure, Williams and Yearwood were able to build the relationships and caché that made a career in basketball possible. Williams has been coaching the women’s team at Montreal’s Dawson College for over twenty years, while Yearwood has coached the men since 2003. “I’d probably be in a state of hopelessness,” added Williams, about White’s impact. “I have a pretty positive life right now. A lot of it is because of him.”

WSA should have marked the beginning of a period of sustained success for Montreal basketball, with more programs to support the increasing interest from migrants in the late twentieth century. Canada, though, was a hockey country. The contemporary version of that sport had been developed by wealthy, white men at McGill University in the 1870s, and it continues to be predominantly played by that segment of the population, with the NHL being the least racially-diverse professional sports league in North America. Hockey receives a seemingly endless allocation of resources from government and corporate actors attempting to bring people together by instilling “Canadian” and more implicitly, “white” ideals into young players such as team spirit, resilience, integrity, and a sense of national pride. The powers that be lacked the imagination to see how basketball—accessible and attractive to kids from marginalized or low-income communities—could bring Canadians together in a similar, perhaps even more wide-reaching way, turning their backs on players from marginalized backgrounds despite them being responsible for Montreal’s first basketball revolution.

The borough where Williams and Yearwood first played looks vastly different after a couple decades of gentrification. Today, it’s full of sleek condo buildings and people who might have no idea what their streets used to look like, or who used to play there.

Growing up in New Waterford, Nova Scotia, Richie Spears dreamed of playing for Team Canada. And after leading the Acadia Axemen to a second-place finish in the 1963 Canadian university championships, the six-foot-two shooting specialist got to represent his country, joining the team for the 1967 Pan American Games. A few years later, in 1972, he flew to Montreal to interview for the head coaching position of the men’s basketball team at Dawson College—the largest English-speaking Collège D’enseignement Général et Professionnel (CEGEP) in Quebec, and the same school where Yearwood and Williams coach today. The CEGEP system is a series of publicly funded colleges that give high school graduates an additional two-to-three years of preparation before university, enabling hundreds of Quebec’s best basketball players to get more experience, though they head to university at a later age.

Basketball was beginning to develop in the province: as White was founding WSA, Robert (Bob) Comeau began running the provincially funded organization Basketball Quebec as a way to regulate basketball in the province. In its early days, it consisted of a handful of volunteers going to school gyms to make sure that physical education teachers were “aware what basketball was,” says Carl Comeau, Bob’s son, who now runs it. “And that they have the facilities, the rooms and gyms to be able to teach it.”

But hockey was still the province’s main game, and the athletic director at Dawson College told Spears as much during his job interview. “I said, ‘We’ll change that.’ And I think we have,” says Spears. The Dawson Blues practiced seven days a week and built a culture in the Showmart gym, where hundreds of Montrealers would descend upon the aging facility across from the bus station to watch the best players in the province run roughshod over their competition. “Spears came in and he just took Montreal and said, ‘This is going to be a basketball city. And I’m going to make basketball really important,’ ” says Eddie Pomykala, who lost just one league game in his three years playing under Spears.

Spears didn’t only impact men’s basketball. Ahead of the 1976 Montreal Olympics, the province started injecting real money into each sports federation in an effort to place as many Quebec athletes as possible onto the Canadian delegation. At those Olympics, women’s basketball would be making its debut and Montreal would be positioning itself as a world-class city. Spears was hired as the head coach of Team Quebec, the all-ages team composed of the province’s best women competing in the annual Canada Games. He held tryouts in Montreal, running the athletes into the ground—sometimes literally.

At the time, women’s basketball was taking a new shape amidst the growing women’s liberation movement of the 1970s. Tennis star Billie Jean King used her platform to help pass Title IX in 1972, which prohibits sex discrimination in American federally funded school programs, including sports. Spears treated the women exactly the same as he would the Dawson men’s team, and the two would be trained under the same regimen. “I took it seriously and I worked them very, very hard,” Spears says. The Quebec women’s team won silver at the 1975 Canada Games before sending three women to represent Canada at the 1976 Montreal Olympics, including Sylvia Sweeney, who went on to captain the national team for seven years.

After the Olympics, another government initiative would dramatically reshape Montreal basketball: the passing of the Charter of the French Language (Bill 101) in 1977. Under the Parti Québécois government of René Lévesque language laws shifted and immigration from French-speaking countries like Haiti, St. Lucia, and the Republic of Congo was actively encouraged. At the same time, anglophones started leaving; about 300,000 would depart the province over the next forty years. “A lot of the English-speaking people left with their [basketball] knowledge,” says Joey McKitterick, who runs the West Island-based organization Brookwood Basketball and the MBL. Following Bill 101, Lévesque’s government had a mandate to place French-speaking players and coaches onto provincial teams, which moved to an age-group model in the 1980s. As Basketball Quebec established connections with more francophone programs in Laval, Quebec City and Gatineau, Montreal kids struggled to get attention. “I wouldn’t say they had a quota,” says Igor Rwigema, founder of QC United basketball club. “But most of the kids in Montreal felt like they didn’t really get a chance.”

Though the language policies may have led to Black francophone immigration, those communities were still under-resourced and marginalized compared to the white francophone majority, facing worse outcomes in everything from healthcare to immigration to education. The same provincial government that failed to ensure equal access to healthcare showed bias when it came to competitive sports. Some program directors felt that Basketball Quebec was more concerned with receiving the government funding that came as a result of winning the annual national championships, than fostering relationships with players and programs in urban Montreal.

“I felt like guys in my neighbourhood didn’t really take a liking to it,” says Ibrahim Appiah, who coached at QC United and now works for one of the city’s professional teams, the Montreal Alliance. “We felt like they [Basketball Quebec] didn’t necessarily understand us. They didn’t necessarily allow us to express ourselves freely when it came down to that aspect of it.” The administrators and coaches were traditionalists who had trouble connecting with Black players, promoting a style of play that sometimes failed to appreciate the speed, athleticism and competitive nature that kids from places like Little Burgundy—who learned the game outside—brought to it. (A similar dynamic played out at Team Canada in the eighties and nineties.) Plus, it cost hundreds of dollars a summer to play for Basketball Quebec’s province-wide Team Quebec—money many Montreal-based players didn’t have. Without the money to burn or the knowledge about where to get identified by American NCAA programs in order to turn pro, most of Montreal’s best young players were not playing with Team Quebec or in any organized league—they were playing at the parks.

Chris Boucher was a tall, lanky teenager who wanted to do nothing more than shoot threes. The only problem was that there was never anywhere to practice. “There was a lot of people interested in basketball,” Boucher says. “Just not enough places to play.”

That space issue reached a boiling point by the turn of the millennium, when the appetite for basketball in Montreal was growing due to the emergence of the Toronto Raptors in 1995 and the Canadian men’s team placing seventh at the 2000 Olympics. However, with roughly 7,000 publicly funded ice arenas and zero indoor basketball-specific facilities, accessible basketball courts have always been hard to come by in Canada, especially in communities that lack government investment and have a limited number of safe, public spaces for kids to practice their skills.

The lack of investment in certain neighbourhoods and sports predominantly played by Black people tells a story indirectly. To this day Hockey Canada receives more than what Canada Basketball gets from the federal government each year. In Quebec, public funding and corporate sponsorships for sports was poured into hockey facilities and programs—a conspicuous funding discrepancy in a province whose identity is built on white French Canadian experiences of grievance and nationalism.

When Boucher was growing up in the early 2000s, his options were limited: wait hours to join a game on one of the few functioning courts in the city, or—in the case of then named Parc Kent, near where he lived—shoot on a rim with no backboard. “That’s how I really learned how to play,” he says. He developed a high-arching jump shot, launching it into the net with a form that resembles a medieval trebuchet. “I think my motion is kind of ugly, but it still goes in,” he adds. “I’ve been shooting that way forever.”

Boucher was born in the island of Saint Lucia, where French is commonly spoken, in 1993. He arrived in Montreal at the age of five and by the time he was seven, he and his mother had moved to the densely populated neighbourhood of Montreal North, a low-income borough far from well-known tourist areas like the fabled cobblestone Old Port. With 80,000 residents, Montreal North was the fifth-largest city in Quebec before being placed under provincial trusteeship following the Great Depression, merging with the city of Montreal in 2002. The neighbourhood is a mix of panelled single-family houses, apartments, and classic Montreal triplexes and duplexes dotting the streets. Grassy parks are full of kids playing during the day and teenagers surreptitiously drinking beer at night—it looks like a lot of neighbourhoods outside of downtown.

“One day we were living in the mountains on an island,” Boucher told The Players’ Tribune. “And the next day we were in Canada, in a big city.” By the time he was seven, Boucher lived with his brother, younger sister and mom in a one-bedroom apartment, merging with a diverse community in Montreal North, including many fellow West Indian migrants who arrived in Montreal searching for more opportunity and a connection to francophone culture. They worked hard to make ends meet in a rapidly evolving province. “It was tough, I’m not gonna lie,” Boucher says of his childhood.

At sixteen, Boucher was left without a place to live after fallouts with his parents. He worked as a line cook at St. Hubert and rode the 380 Henri-Bourassa bus back and forth at night. The tall, thin Boucher would slump in the back corner of the bus with his oversized jacket and portable radio, listening to Bob Marley, Tupac, Lil Wayne, Biggie Smalls and 50 Cent. “That was just peace,” he says. “All I had to do was listen to music and walk around and wish for a better day.”

Like Trevor Williams before him, basketball had become a solace for Boucher—a place he could go for a moment of peace amidst volatile realities, like not knowing whether his family would take him back, or if he could come up with $2.75 to ride the overnight bus. Basketball was a confidence-builder; Boucher felt like he was on top of the world when he would soar above grown men defenders and hang on the rim after learning how to dunk at seventeen. In his personal life, he felt directionless. On the court, he was a superhero.

Boucher would play basketball at all hours of the day, going to the park at five in the afternoon and staying until midnight. After hitting a growth spurt that brought him close to six-foot-nine by the time he was nineteen, he started to gain some notoriety at Parc Kent and was often picked to play with the older players on the main court. He could shoot the lights out of the ball and deter shots at the rim, but nobody outside was taking notice. Aside from Basketball Quebec, which selected teensto play on boys and girls teams in the summer months, there were two major clubs in town: Brookwood Basketball and Sun Youth, recreational teams that have been around for decades teaching kids fundamentals. By the late 2000s, neither organization had enough resources to support the growing number of players that would show up to their tryouts. “I went to a Sun Youth tryout at the time and I think there were about probably 300 kids,” says Rwigema, noting that players would often be sent home if they missed a single layup. “We lacked the infrastructure to really support those kids and identify them,” McKitterick adds. Rwigema addressed the problem in part by founding Alma Academy in 2012, Quebec’s first traveling basketball prep school in the small town of Alma.

That same spring, Boucher was invited by some friends to play in the annual Hang Time tournament in Little Burgundy, which brought together Montreal’s best teams. Boucher—playing organized basketball for the first time in his life, with ten of his neighborhood friends and no coach—dropped forty-four points on the best club team in the city. Boucher went home happy with himself after dominating a team filled with similarly-aged kids who had offers from top NCAA schools, but he didn’t think anything of it. “I was like, man, nobody came to see me,” he says. The next day, however, Rwigema was at his father’s door, waking Boucher up and recruiting him to Alma Academy.

At Alma, Boucher had a couple of big performances against top American prep schools. Suddenly, there was a line of Division I coaches recruiting him. “Every school you can name was after him,” Appiah says. Boucher attended the University of Oregon in 2015, breaking out as one of the best big men in college basketball before joining the Toronto Raptors in 2018. He became the most accomplished bench player in the history of Canada’s lone NBA franchise—with an NBA championship in 2019 and more than $50 million in career earnings. “I could have had a bad day and never made it,” Boucher told Sportsnet.ca about the Hang Time tournament. “So I don’t really take it for granted when I tell my story.”

Boucher could have slipped through the cracks like many Montreal ballers did before him, racialized players who were failed by the province’s lack of investment into their communities. By the time he started to excel at basketball in 2012, however, things had changed: there were blacktops with competitive games around the city, showcase tournaments like Hang Time and Sun Youth Holiday Classic, schools like Dawson and Alma, and club teams like Brookwood and QC United that were identifying and developing players at the grassroots level. This infrastructure to support young talent was developed by those who were once in that position, and knew what was missing. “I got lucky that somebody saw me,” Boucher said. But luck is only ever part of the equation.

Feras Saaida decided to become a coach at fifteen. “I knew this is what I wanted to do, developing players and creating an environment where guys can reach their maximum potential,” he says. Having been on Vanier College’s D2 CEGEP basketball team from from 2009 to 2012, the former player turned coach understands the particularities of the sport in this city. “I think the reason why everybody is so supportive and passionate is an underdog mentality coming out of Montreal,” he says.

He credits the experience of being different as a driving force, noting that many of the twenty-first century players who went from Montreal basketball courts to the NBA are immigrants to Canada. “I coached in the same program where they grew up, and they were all immigrants that, at a young age, had to figure life out,” explains Saaida. “I think we have all the talent. There’s so much here. I just think there’s a lack of support.” Boucher describes a similar tenacity coming out of Montreal players: “We’re all fearless.”

Saaida has also coached Team Quebec, mentoring younger guys with dreams, including then Vanier player Karim Mané. “We had the only player ever that went from CEGEP straight to the NBA,” he says of Mané’s 2020 signing with the Orlando Magic. He describes Mané’s path as a turning point for professionalization of the sport in Montreal, as some American coaches and scouts may not have previously understood the unique CEGEP system in Quebec. “We had NBA teams flying to Montreal to watch him play. They would fly to games, fly to practices.”

Saaida thinks what separates those with the potential to soar above the pack is teachability and a consistent willingness to improve. In the last ten years, he says, the sport has seen progress: the implementation of full-time assistant basketball coach positions in Quebec universities. “They’re going in the right direction, but going there slowly,” he notes. “If we had institutional support in comparison to other places, I think it would be a monster of a basketball city. But that’s where we are right now. And the positive part is it did get better.”

Conditions can change because of people who care enough to take action. Nelson Osse was born in Haiti and grew up in the Parc Extension neighborhood of Montreal to a family of Haitian immigrants—one of the 140,000 Quebecers of Haitian descent living in the province, making it the largest racialized group in Quebec. After playing high school basketball, Osse failed four out of seven classes in his first CEGEP season, forcing him to stop playing basketball midway through the academic year. “This is exactly what pushed me to put together a program that would help young men not only succeed on the basketball court, but also in class,” he says. Osse started the Parc Ex Knights basketball program in 2005 to mentor the growing number of first-and-second generation Haitian Canadians who were falling in love with the sport. “I had a few people look out for me [growing up]” Osse says. “So when I got a chance to be in charge of my organization, it was always about giving back and making sure that I was doing the same thing.”

Parc Ex became known as one of the best programs in Montreal due in large part to its partnership with the city to access the William Hingston Centre near Parc metro station: a modern three-floor red-brick building with glass windows, a boxing gym, and some of the only indoor basketball courts in northern Montreal. Lu Dort was twelve years old when he first tried out for the Knights. His parents, Lufruentz Dort and Erline Mortel, emigrated from Saint-Marc, Haiti, to Montreal North in their early twenties, raising Dort and his five siblings there. Dort, inspired by his best friend, Shawn Barthelemy, started playing basketball after being a soccer goalie for most of his childhood, playing down the street from their houses at the easily accessible Parc Saint-Laurent. “It was the place where we were feeling safe and we knew that we could get better,” Barthelemy says. They challenged the older boys to games before eventually hearing about a program attracting fellow amateur players to Parc Ex.

The boys traveled an hour and a half each way by bus and metro to try out for the Knights. And while Dort struggled to make a layup in his first experience playing organized basketball, he made his presence felt on the defensive end. Dort was the final player selected because of his athleticism, energy and toughness, spending entire days in Parc Saint-Laurent or Parc Ex to hone his skills. “Basketball basically saved me,” Dort told the Montreal Gazette.

Dort joined Brookwood Elite at age thirteen, an initiative by McKitterick that had started bringing together the best players from across the city (after McKitterick had taken what he thought was a talented Brookwood team to a tournament in the US, where they were thoroughly dominated). He had connected with other local coaches and programs in the late aughts, such as Osse’s Parc Ex Knights, to form a team that would travel to America in the summers and showcase themselves to NCAA coaches. “Everybody was stronger, taller and probably faster too,” says Barthelemy, the point guard of those teams. “If we put our mind to it and played hard, we knew we had a chance to compete. So that was really our mindset. We were trying to outwork them.”

Unlike a lot of his teammates, Dort wasn’t afraid of the American competition. He set the tone by guarding the opposing team’s best scorer every game, embracing the challenge and using his unending pool of competitive energy to outwork them. He hit a growth spurt and started using his six-foot-four, 220-pound frame to overpower opponents, going on to play for three different prep schools in America and Ontario while learning English by watching reruns of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. After sorting through a host of Division I offers, he landed at Arizona State in 2018. He’s since blossomed as one of the best two-way players in the NBA, known for using a physical brand of defense to stop the opposition while knocking down a high percentage of three-point shots. The main characteristic that enabled Dort to go from struggling with layups to stardom is the same intensity and persistence Boucher and Saaida describe. “We’re dogs, man,” Dort once told NBA Social. “We go out there and we represent. We don’t back down from anything, and that’s just how we represent our neighbourhood.”

After Dort broke into the NBA in 2019, fellow Montreal-born players Bennedict Mathurin, Olivier-Maxence Prosper and Jahmyl Telfort followed a similar route there in the early 2020s, going from Brookwood Elite to the NBA. The rise of basketball in Montreal is a lesson in community-building; while government agencies have been focused elsewhere, people like Bob White, Richie Spears, Igor Rwigema, Ibrahim Appiah, Joey McKitterick and Nelson Osse have been building a framework from the ground up, often in spite of the powers that be.

That’s not to say that the rise has lifted all boats—women’s basketball continues to lag far behind the men’s game. As systems built on anti-Blackness shaped the lack of infrastructure for the sport in the city, institutional sexism too has led a generation of Montreal-born players like Sarah Te-Biasu and Cassandre Prosper to grow up without consistent access to gyms or reputable clubs to showcase them to American coaches. “On the men’s side, they have a lot of teams,” says Te-Biasu, who is entering her first year playing professionally in Sweden. “But on the girls side, it was really, really tough.” The best women’s players in Quebec today are left playing against the boys—like Sweeney did almost sixty years ago. “Let me be a role model for the next generation,” Prosper, a top-ranked prospect at Notre Dame, says. “I didn’t have a woman to look up to and be like, she’s made it this far. Even now, I’m in college, but I’m gonna make it to the W[NBA] to show every girl in Montreal that they can do it, too.”

You can feel the impact of the Montreal basketball boom—and the men who have become its stars—walking through the streets of Little Burgundy, Montreal North, or Parc Ex, where Montreal’s best players return every summer to give back to the communities that raised them. “Canada saved me. You want to be able to give back to the country that kinda saved your life,” Boucher says. As the first generation of Montrealers to have this much success, they give back in the form of basketball camps hosted by Mathurin and O-Max Prosper each summer; non-profits founded by Boucher and Dort that help kids with school and sports; and refurbished public spaces such as Dort’s childhood court of Parc Saint-Laurent, which now has a colourful mural and glass backboards that have become the pride of the Montreal North. “It’s still dangerous, but I do feel like they’re making changes,” Barthelemy says. “I can smell in the air that it’s getting better.”

And while there are still problems in the Quebec basketball infrastructure, with programs working in silos, a lack of indoor facilities, and some of the best players choosing to compete in Ontario’s premier high school leagues instead of CEGEP, the sport is growing rapidly. Even the government is getting in on the fun with the development of Sport-études: provincially-funded grade-school programs that prioritize sport specialization for the highest achieving segment of the francophone population. At the same time, Black players, especially anglophones, continue to face racism and barriers to success, with significantly fewer resources poured into English public schools than French ones.

After making the jump from Montreal to the NBA—fighting through educational and racial barriers—players like Boucher and Dort have become local icons, setting the province on a new direction. Soon, young kids will be able to go to a WNBA Toronto Tempo game. Or perhaps, they will even live long enough to watch an expansion NBA team in Montreal’s Bell Centre, and hanging above them—not so far from Lafleur or “Rocket” Richard—will be the jerseys of Montreal’s first basketball heroes. ⁂

Oren Weisfeld is the author of The Golden Generation: How Canada Became a Basketball Powerhouse. He covers basketball and the intersection of sports and politics for the Guardian, Toronto Star, VICE, SLAM, Complex, Sportsnet and more.