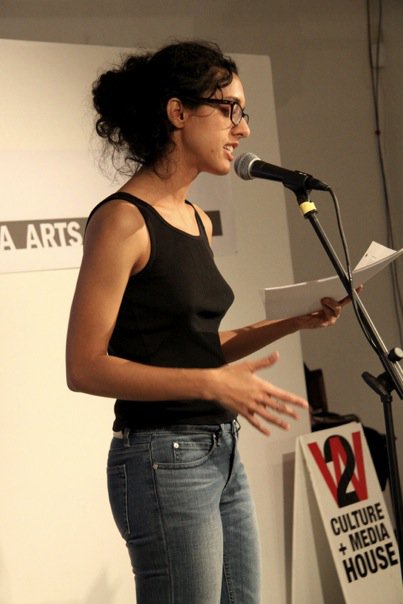

On Reviewing: Interview With Sonnet L'Abbé

Sonnet L’Abbé is the author of two collections of poetry, A Strange Relief and Killarnoe, both published by McClelland and Stewart. She won the Bronwen Wallace Memorial Award for most promising writer under 35, and the Malahat Review Long Poem Prize, and her work appears in the Best Canadian Poetry in English 2009 and 2010. L’Abbé has taught writing at the University of Toronto’s School of Continuing Studies. She reviews poetry for the Globe and Mail, Canadian Literature and other publications, and is currently working on her PhD in English Literature at the University of British Columbia.

Lemon Hound: What do you think the purpose of a review is? If you also write about books on a blog, why? What does blogging let you do differently?

Sonnet L'Abbé: Ideally, a review condenses one knowledgeable and generous reader’s full experience of a book. By knowledgeable I mean having a sense of what constitutes quality across a range of genres, and by generous I mean starting from a position of hoping to love the book. A reviewer should give an opinion: signal overall impressions, give some specific moments of admiration, and say what aspects of the work, if any, prevents her from being unequivocally enthusiastic about it. This seems like common sense, but so many reviews avoid talking about shortcomings. A review should take a position, give context to the degree possible and necessary, and should help people decide if they want to buy the book. The kind of information and level of detail a reviewer might pass on in a review depends on the intended audience, i.e. academic or popular.

LH: If you write reviews, how would you describe your approach, or method? Do you offer or engage in exegesis, theoretical, academic, reader response, close, contextual or evaluative readings? If you don’t write but read reviews, what aspects of reviewing do you notice?

SL: My method: read the whole book through once taking notes with page numbers, close the book and write overall impressions, go back to the book via my notes to try to articulate what I think the aesthetic aims of the work are, then decide if I think those aims are worth having spent a book’s worth of work on and whether or not the book achieves what I think it set out to do. Close reading helps me get a sense of the author’s level of technical control and clarity. I often like to familiarize myself with an author’s previous work, as deadline permits, to be able to speak to the author’s preoccupations and new choices.

LH: What do you think makes for a successful review? Is there an aspect, a stylistic choice, or perspective that necessarily produces a more significant document?

SL: A successful review accurately reflects the book’s achievements both as a work one might read randomly – for a broad audience of readers - and as one read in the context of similar work, for more specialized audiences. A particularly successful review reads a book in its long, literary, historical and commercial contexts and can place it accurately in terms of its significance in its field. If the reviewer really digs the book, her review should risk a persuasive stance toward making people want to buy the book and read it.

LH: When you review, do you focus on a particular text (poem, story), the book at hand, the author’s body of work? Do you think this choice of focus influences criticism, or your own criticism, and if so, how?

SL: I always want to engage with the whole book. (I'm always amazed at how many people ask me if I read the whole book when I review one, and who of those are surprised when I say yes, I often read them more than once!) If a particular poem or story in a book seems exemplary, either because it helps me to describe the merits of the larger work or is the only piece worth spending time on, I’ll let the review take shape accordingly. I like to have a sense of where the book is coming from, that is, I like to understand it as one step in a writer’s career and be able to comment on that particular writer’s favorite concerns or evolution of style. I can’t always read an author’s whole backlist, though, so if I don’t know an author’s earlier books I’ll try to get them from the library and at least flip through them.

LH: If you also write non-critical work, how different is the way you approach reviewing or critical writing to the way you approach your own “creative” writing?

SL: Critical writing feels much more straightforward – easier, in a way. The text is already there, waiting to be commented upon. The steps to reviewing - i.e. reading the book and choosing a response to it, working to a deadline and a specific wordcount - all provide pretty clear expectations about the way a piece of critical writing will succeed, or at least be functional. (At least, it feels that way to me, but obviously the dialogue you’ve initiated, Sina, and the responses of other reviewers show how diverse our understandings are of the goals and nature of reviewing.) My creative writing doesn’t always let me know up front what its goals are. I don’t know how a creative piece I’m working on will succeed until it has succeeded, and sometimes I don’t recognize or come to a final decision on a piece’s success or failure until a long time after it is written.

LH: Have you been in a position where you have had to write about a book that you don’t care for, or a book that is coming out of a tradition that you are perhaps opposed to, or resistant to on some level? How do you handle such events? Or how have you noticed others handle these events?

SL: Totally, yes, I have been in both situations. Writing for the Globe and Mail, I’m often in the position of only having so much space to speak about books and have some latitude to choose what I will talk about, so the desire to give space to work that deserves a wide audience often makes it easy to not write about books I don’t like. Sometimes, though, I’ll be assigned a book that will already have some readership because of the profile of the author, or ask for a book by someone I’m really interested in, then think that it sucks. So far, I’ve always handled this by writing through it. It can feel like one small step in a slow career suicide to say I didn’t like so and so’s book. Maybe one day enough of those steps will add up to a fatal fall, but so far, not. So far, writing through my dislike of a book, with a commitment to fairness and awareness of my own tastes, has almost always moved me from my first self-audits to a full and backed-up realization of why a book didn’t work for me.

LH: What is the last piece of writing that convinced you to a/ reconsider an author or book you thought you had figured out, or had a final opinion on or b/ made you want to buy the book under review immediately?

SL: I wish I had reviewed M. Nourbese Philips’ Zong! for the Globe and Mail when I had the chance. I’ve written about “Discourse on the Logic of Language” for the Books section, and respect Philips’ work a lot. Zong!’s mission is important, and its conceptual presentation made sense to me, but on first read it felt drawn out, as if what would have made a tight long poem had been stretched to book length. I’m always torn when work that speaks to my individual likes around political voice doesn’t satisfy me formally/technically (pace the illusory separateness of form and content here). Kate Eichhorn’s interview with Nourbese Philip in Prismatic Publics made me wish I had still given the space to Zong! to say what I had to say and bring more people to the work. I asked Martin Levin if we could still do it, but it was about one season too late – so, dear readers who haven’t already done so, go check out Zong!

LH: Is there a quality you are looking for in a review that you haven’t found?

SL: There are a couple qualities that I wish I would see more often, one of which is a sense of responsibility to articulate the larger project of a book, rather than simply synopsize its plot – I suspect this comes out of my academic training and seeing my job there as helping students, the readers I’m training, to look for the ethical, social, conceptual or representational question that the book is asking. It can be hard to locate the heart of a book, but I despair of reviews that don’t even try to demonstrate that one might look for the large questions a book can pose.

LH: Critical work is increasingly unpaid work; will you continue to do this work despite the trend? Do you see this trend reversing, or changing course?

SL: For the past few years I’ve tended to only say yes to reviewing for pay. Now that I’m working on a PhD, I’ve begun reviewing in my field for scholarly journals that don’t remunerate - academic capital is a kind of pay, though. I don’t know when I’ll next be in the position to do critical work for free, but I can imagine a number of scenarios where I would. I can’t say many hopeful comments about the trend. The print publishing and online publishing games, scholarly and popular, are seeing such huge challenges to their business models that all kinds of writing, not only critical writing, are increasingly threatened by a dearth of paying outlets. I do think that it’s important that as professionals, writers expect to be paid and that we keep looking for ways to hold the big machine accountable to our labour.

LH: What do you hope to achieve by writing about writing? Do you believe that reviews can actually bring new readers to texts?

SL: See above. I definitely believe reviews bring readers to texts; I’ve had readers of my reviews, and writers whom I’ve reviewed, enthusiastically tell me as much. Reviews are such an important part of the conversation and community that we create by writing books. They are the vehicles by which a book is publicly heard and reflected. I imagine writing a book that is never reviewed is a like sending your most heartfelt email out to your list of friends and never hearing back. Writing about writing, and reading writing about writing, sustains me. It’s shop talk, and – particularly because I so rarely poke my head out of my shop – I love the camaraderie and shared grumblings of fellow shop talk.

(From Lemon Hound.)

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—Revivifying CanLit Criticism

—In Defense of Blogging

—Interview With Alexander MacLeod

Subscribe — Follow Maisy on Twitter — Like Maisy on Facebook