Liquor Run: the Slow but Steady Rise of Moonshine in Canada

One of my students, grinning at me, pulled out a big plastic bottle full of something clear from her bag. It was early Wednesday morning and we'd been talking, a few Wednesdays back, about her aging father's hobby: distillation. There are thousands of moonshiners in Hungary, and the fruits of their labour fuel the heavy drinking that is part of nearly every function. What I'd received was a litre of handcrafted pear liquor of unknown strength. Teaching English abroad has its perks.

If our roles had been reversed, and she had been teaching me Hungarian in Montreal, I'd have had a much harder time returning the favour. In Canada, the artisan's craft of distillation has become something sinister.

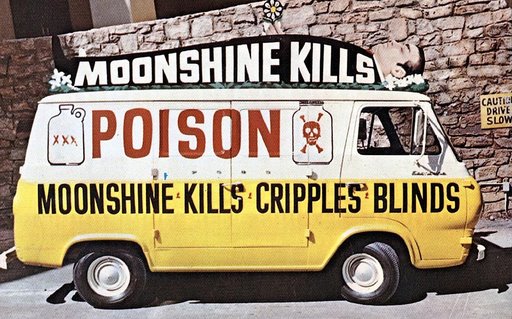

The word moonshine conjures up fears of blindness, explosions and jail time, but the logic behind these fears is suspect. As with most things homemade, if moonshine differs from commercial alcohol, it is simply less adulterated, more flavourful, and tweaked to satisfy individual tastes instead of national averages. We often think of moonshine as some sort of extreme drug unrelated to other spirits, cooked up by backwoods criminals escaping the law. How did we get so mixed up?

Moonshine can be anything from the purest of vodkas to the tastiest scotch, so long as it's produced under the radar of the law. There is often reference to the potency of homemade spirits, but all spirits, commercial or not, are distilled to high concentrations and then watered down—it's just that some moonshiners skip the last part.

The Canadian conception of moonshine is steeped in prohibition-era bootlegging and the influence of one wealthy Montreal family. During the 1920s, Samuel Bronfman, then owner of Seagram's, had partnered with Al Capone to keep America's thirst quenched with Canadian rye. Together, Bronfman and Capone moved incredible volumes of whisky southward, and the Bronfman family became one of the richest in Canadian history.

Today, Samuel Bronfman's son, Charles, is worth $2.4 billion, and is the eighteenth-most wealthy person in Canada. The Bronfmans, three of whom have gone on to become Companions of the Order of Canada, weren't selling moonshine—they were directly competing, and winning, against American moonshiners for their share of Capone's business.

Meanwhile, small-time distillers in the hills of Tennessee were loading xxx-marked jugs by moonlight into the trunks of souped-up cars–ready to outrun police. The xxx meant triple distilled–a product of highest purity. Both stock car racing and the term "moonshine" were born in those hot southern nights, and both took a long time to become popular in Canada.

Contemporary liquor, like music and art, has been divided into genres and sub-genres. But there are very few liquor stores that feature an "experimental" section; there is no place for bathtub gin, no home for a 160-proof brandy made from old raisins. Ultimately, the question, "What is moonshine?" is silly. Instead, try asking a moonshiner, "What is this and how did you make it?" and you might get into a discussion that sounds familiar if you're used to discussing post-punk, no-wave, or whatever.

It's hard to meet moonshiners in Canada, but if you try hard enough, all roads lead to Ian Smiley. Smiley is North America's moonshine mogul. From his suburban Ottawa basement, he operates several high quality copper stills to produce his own supply. He also runs a mail-order business, where sells all the equipment and ingredients anyone might need to become a moonshiner in their own right through Smiley's Home Distilling, his very successful website.

Smiley is a home distilling legend. Last winter I was in his basement with a Montreal distiller friend of mine, on a pilgrimage of sorts. He told me it is nearly impossible to become a distiller in Canada without doing it illegally for a while. If you want to go commercial in Canada, you first have to build a distillery, and then ask for permission to operate it. "The way the routine goes, the government makes you have all the equipment first, before they'll sign the license. You have to have the still and everything," he said.

Stills aren't cheap. Even my Montreal friend, whose still consists of an old beer keg attached to a series of copper pipes and coils, has managed to invest hundreds of dollars into his illegal kitchen distillery. The cost of commercial stills starts around fifty thousand dollars, not to mention the cost of the building and renovations, all of which need to be done before ever getting government permission to make liquor.

Craft distilleries are beginning to pop up in Canada, but there is a good chance all of the small distillers in the country started by doing it illegally, and under Smiley's indirect tutelage. Smiley's book, Making Pure Corn Whiskey, is a moonshiner's classic. Its 186 pages cover all the technical knowledge needed to turn crude household items like hot water tanks, copper pipe, thermometers, and hot plates into weird but functional devices to hide in your basement or shed.

Craft distilleries are still few and far between—there are only about ten legal small distillers in Canada. By contrast, in 2009, a 47 percent share of the global premium spirits market was owned by just two companies. Whether you're sipping Hennessy, Lagavulin or Crown Royal, you're probably buying a lot of your liquor from a company called Diageo. They own 13 single malt scotch distilleries, as well as Smirnoff. Diageo and the second largest liquor manufacturer in the world, Pernod Ricard own the bulk of what used to be Seagram's (read: Bronfman) assets. If Diageo or Pernod Ricard have any interest in small, local distilleries, it is in acquiring them.

Back in Hungary, Diageo has had much less success. Instead, the Zwack family, Hungary's own liquor barons, have the lion's share of the market. And even though every Hungarian knows someone who makes their own pálinka, the Zwacks' business is booming. Their many varieties of pálinka are often bought at airports and train stations, along with big salamis bearing the Hungarian flag, as ways to remember a trip. But remembering Hungary through Zwack pálinka is like remembering Canada by drinking Canadian Club.

Describing "real" pálinka can be difficult. According to European law, it is subject to just three regulations: it must be made of Hungarian fruit or herbs, it must be made in Hungary, and it must contain between 37.5 and 86 percent alcohol.

These rules reflect the culture of distilling in Hungary. It is one that is accustomed to variation, and is influenced by a huge number of individual distillers and individual tastes. And though home distilling was illegal for years—as it still is in many countries—Hungary legalized the practice in 2010, since it was so widespread anyway.

Perhaps we are on our way to such a culture in North America. "Home distillation is de facto legal in Canada," says Smiley, who has repeatedly asked the Canada Revenue Agency whether his business steps on any toes or is likely to land him jail time. According to him, there is no enforcement of Canada's ban on home distillation, and most people in the government don't even know it exists. "As long as you're not selling it, nobody cares," he says.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—We'll Never Be That Drunk Again

—Places to Drink Outside in Halifax

—Ghosts, Fire and Forgetting

Subscribe — Follow Maisy on Twitter — Like Maisy on Facebook