Titus Andronicus and the Trouble with Onstage Rape

Did William Shakespeare really pen Titus Andronicus? Does it matter? The play's unremitting violence is what's often brandished by the con side of the debate, but I don't think morality should be used to relegate authorship from one camp to anon's.

Anyway, I'm just a girl who likes to go to plays—I'm no scholar. But Shakespeare's got my vote on Titus Andronicus; I'm all for thinking it's Will's first. Titus has that fresh-out-of-school first-art-show look-how-well-educated-I-am show-offy pastiche mixed with the highbrow ideology of youth, and I think of Titus as Shakespeare's video-game period, his latent adolescent prodigiousness. Something that could have been thought up by one of those young-man philosophy students I'd see tooling around the Cégep du Vieux Montréal circa the 1995 Referendum, all curly-haired and hand-rolled cigs and arguing over who was Marxist and who was colonized.

Titus Andronicus is just as earnest, but the tragedy is on a grand scale, in the epic Greek variety, with its sloughing off of body parts and human sacrifice. It's a tragedy that pits filial love against nationalism. I see the play as a philosophical argument played out to extremes, played out so flamboyantly that it becomes an absurd, Quentin Tarrantino-style bloodbath. Its violence is disturbing, of course, but the violence itself may be seen as commentary: Titus Andronicus shows that violence can be teased into ritual of any kind, a maniac's ritual, a country's ritual, a ritual for the gods, but what becomes clear is that in this play, death is meaningless, regardless of how it is provoked, or for what end. We are slain and maimed and we maim ourselves for naught. It's a show of agonizing agnosticism. It's a play that depicts the artifice of wanting to live for those we love. And our devastation when we are consumed by those people, and ideas, we love.

So I was keen to see the Montreal Shakespeare Theatre Company's recent staging of the show. I asked a boy to come along. I warned him about the rape and the cannibalism and gave him my spiel on nationalism and we sat in our prime spots right in the middle of everything.

I went to this high school in Montreal West called Royal West Academy (yes, of course we wore uniforms), which had an O-Captain-My-Captain kind of English teacher (Mr. Floen!) who, year after year, staged some pretty spectacular Shakespeare productions. It gave us all a real love of theatre and of Shakespeare in particular, and I'm glad we have something called the Montreal Shakespeare Theatre Company in town, and I'm glad that there are people still excited enough about Shakespeare—and in particular of this play—to put it on. I've seen Titus in French, when the Théâtre Omnibus staged a fantastic version of it a few years ago in the East End. But, apart from Julie Taymor's film version, I'd never seen the play produced in English.

I wasn't expecting to have fun, exactly. But I wasn't expecting to suffer from artistic PTSD either.

So we were sitting there and it was cool. I was fine with the awkward humping onstage for a while—though it was sort of a clue that Lavinia's rape was going to be acted graphically.

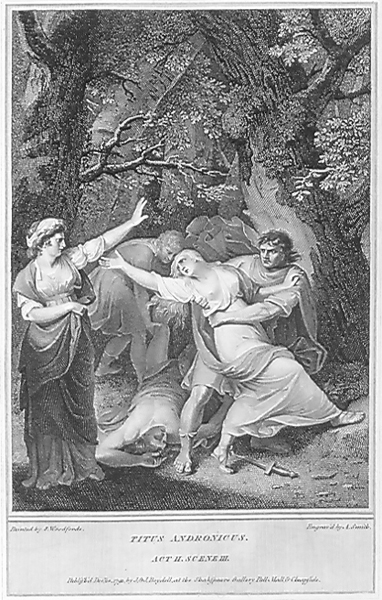

The silences are typically spots where directors will inject new interpretations into Shakespeare—omission's conjectures. And that's the part where we were subjected to a graphic, gory rape. I was at first relieved when the fucked-up Goth brothers carted the poor girl offstage. But from behind the scenes, while Lavinia screamed, the men groaned and panted. Someone clapped their hands to sound like bodies slapping. It lasted a long time. And then, bis, it was repeated. And then they brought her out on stage. Poor Lavinia, played by a sensitive young waif, wailed wretchedly, repeatedly, loudly, writhing naked in pools of fake blood, Carrie-gone-wrong style. I didn't time it. If I say something like ten minutes, I could be wrong. It felt like about ten or twelve theatre minutes, which is probably about five dog years, give or take.

"L'affaire est ketchup," as lequatrieme.com's Yves Rousseau referred to the play's aesthetic. The older I get, the more I think aesthetics are everything. And the problem with the rape scene was that it was going for realistic in an unrealistic framework. Titus isn't reality TV. It's epic; it's absurd. And while both Titus and Aaron were particularly well-played, the company couldn't bear the weight of the story. (Watch Patrick Stewart show us how.) In short: they were trying too hard.

Post-Lavinia's interminable rape scene, my theatre partner and I decided we'd had enough, and we left. Like when you watch a kid freak out with a temper tantrum—how it's best not to egg them on by being too concerned—I didn't want to be witness to this production.

I'm not someone who'd say that you have to think about the moral repercussions of your art—I tend to judge such comments as small-minded. But I do think you have to size up your audience. This felt like performance art on the subject of rape, and Shakespeare was just the fancy backdrop. Why subject an audience to this type of showdown? Didn't the director, Aaron George, ask himself how it would it resonate with the audience? With the women in the audience? I am not opposed to violence in a story, or on a stage. I have, in fact, a soft spot for raunch. But I think the power of that violence was exploited without restraint, without enough thought to a cohesive aesthetic in this production. I don't think it was done intelligently.

Here's why. Rape is a gong already. It's big. It takes up a lot of space. Were I to stage this play myself, I can't imagine not considering that a great portion of my audience is going to be very sensitive to that. Domestic violence kills more women worldwide than cancer or heart disease. The United Nations says: "In the United States, a woman is beaten every 18 minutes. Indeed, domestic violence is the leading cause of injury among women of reproductive age in the United States. Between 22 and 35 per cent of women who visit emergency rooms are there for that reason." There are a million stats like that, really, and this is neither better nor worse than any other. We live with the facts of this violence, all of us.

I don't think Mr. George asked himself how the rape scene could, like CSI: Miami, feed into sexualized notions of violence against women. I don't think he wondered how women in the audience were going to feel when they couldn't escape the onslaught of that traumatic scene.

What if Titus Andronicus were not treated simply as a gory melodrama? You've got to consider that an audience is intelligent enough for Shakespeare's words to reach us without amped-up theatrics. That is foremost why we have bought our tickets. The way a poem needs space on a page, you must leave room for imagination in the audience.

Because while that scene was as abhorrent artistically as it was emotionally, the truth is that in my imagination, I pictured worse. Those nutted-out Goth bros wouldn't have taken their turns so nicely with Lavinia. Omission, suggestion, mystery, beautifully staged trauma could have suggested worse. I wanted this to be good. I want exceptional English-language Shakespeare produced on a regular basis in Montreal. I want people to take risks. But I want those risks to pay off.

Shakespeare, like Chekov, never gets old, is always appropriate to modern audiences and to modern interpretations. It's tricky to adapt ourselves to, say, The Taming of the Shrew or parts of The Tempest. But like Huckleberry Finn, like Heart of Darkness, we can read these pieces, laden as they are with their prejudices, and still be moved because they are rare, good art on their own, just for language or story's sake, and only more so for their insights into how we behave with one another.

But for now, I'm sticking to Montreal's classic go-to Théâtre du Nouveau Monde when I want to get my Shakespeare. The francos in our town know their bard.

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—Hardwater

—Meet Me at the Met

—To Be, or Not To Be

Follow Maisonneuve on Twitter — Like Maisonneuve on Facebook