Vive le Sandy, Or, How I Learned to Keep Worrying and Tolerate a Submerged New York

Here is what happened to me during Hurricane Sandy: I did not get the least bit wet, but I did get the most bit anxious. Nothing, you see, makes a New Yorker more anxious than the prospect of having nothing to do, nowhere to go, fewer than fifteen projects to work on at once and more than four hours of sleep. Yes, this includes New Yorkers (me!) who have only lived in New York for a few months. In fact, maybe this includes us most of all, as we are afraid of saying no to anything we are asked to participate in. Saying no in New York is a form of weakness. If you say no fifteen other people will say yes, and then suddenly you're on no one's list, nowhere, pal. See? See??!

And what of a city that says no to you? That cuts you off from the places you mean to make your mark? A drowned city doesn't speak, at least not yet.

As far as happenings go, a hurricane is a big one. I hunkered. I purchased water. I pondered buying a candle. In a massive grocery store lineup I pointed at a guy with a candle and said to the manfriend, "Maybe we should buy a candle, like that guy." That guy, in response, nodded yes, and made a grunt that approximated an "mmm-hmm." We did not buy a candle, but we did buy cheese.

Later in my apartment, on the sixth floor of a massive former Jewish hospital converted into profitable apportioned living space (sturdy and brick she is, this vessel, and with windows made for many a Brooklyn winter, aye), I roasted a supply of garbanzo beans meant to sustain the manfriend and I in the event of a power outage. Forty-five minutes later, said beans were safely stored our tummies. Ditto the three bottles of wine we'd bought to last us through the storm. We'd also watched enough Doctor Who episodes to turn everything I said into a British-accented plea for help. Turns out, I cannot ration: not food, not alcohol, not accents.

Texts came then, from my mother and sister, who expressed extreme worry for my safety and told me they were getting their storm news from Nancy Grace (a mistake, they agreed, but nonetheless). When I explained my relative location and safety they calmed, and my mother—my hippie, loose-parenting mother—guiltily requested hourly updates just in case. I complied. She asked if I was scared. I said no, kind of excited actually. "I suppose I always taught you to treat everything as an adventure" she wrote, and I could hear the motherly martyrdom in it, the way mothers can transfer blame like no one else, even pre-blame. Fore-blame, if you will. Should I die, she might be thinking, it was all her fault...for being so damned encouraging in the twenty-nine years of my pre-storm life.

And then: Waiting. Poring over the news like it was our job, watching and "Oh my God!"-ing as stories and photos from Manhattan and the edges of our home borough washed over us. The front of a house fell off on 14th Street, and the photos made it look like a dollhouse. (Someone who lived there loves those oversized French booze posters, mon dieu!) We learned from the Times that these residents paid $4,000 a month for the privilege of watching their fourth wall break off in front of an audience of millions. I wondered if they ever leaned on that wall and thought it loose. As hours went by we watched our favourite and familiar streets fill with water, inquired after friends and family on waterfronts nearby, marvelled at cars in varying states of smash and float. We did this the same way you did—via the internet machine.

And yet, save the occasional wind gust, we were safe and dry. As a power plant exploded in Midtown, blacking out half the island—including the office in which I spend my days and the theaters in which I spend my nights fashioning bits of comedy together like popcorn on strings—I saw the lights above me flicker ever-so-slightly. The water level dropped in the toilet for an hour or two. Across the way a neighbor's rooftop fence blew off its hinges and we watched them try to fix it, criticizing their every decision like Jimmy Stewart and Grace Kelly in some catty version of Rear Window.

"I really should write," I said at times, citing the various sketches needing polishing and the articles I could be pitching at this very moment. My anxiousness would subside, only to reach up and grab my throat suddenly at moments of Ferris Bueller-esque repose. I began to notice a pattern—the more relaxed I was, the more likely these panics became. At a nadir of mental self-flagellation I wrote a frenzied article pitch, and then felt a release of intellectual dopamine that tided me over for the next few hours. I tied the manfriend at Scrabble 274-274. We watched Groundhog Day and two more episodes of Doctor Who.

"I should write some more," I kept saying, out loud, then in my head. There was so much to do! So many pages to begin. The energy I normally used to run from one obligation to another was, unused, draining out of my right foot to the floor, down through six feet of floorboards, into Brooklyn's soil. Was the same thing happening to other writers in my borough, marooned as we were? Jonathan Lethem, what ho? "This is probably good for all of us, this rest from the usual craziness," I said aloud, and I could feel the pinchy nature of my voice, that I was trying to convince myself. The manfriend just shrugged in semi-agreement.

When there was nothing left to watch or fidget at we went to bed. The wind picked up overnight, waking me and bringing me to the window where I could see nothing but the grocery store van in the parking lot, the whipping trees, a hint of skyline. The glass in my windowpane convexed towards my cheek, coldly. I almost opened the window but didn't.

In the morning we surveyed the damage and expressed gratitude that we were away from the worst of it. The subways remain closed, will be until further notice. We are stuck here. "I might write a screenplay while this is happening," I said, a little later, to the manfriend, to myself, to David Tennant cheekily flitting across time and space. I just might.

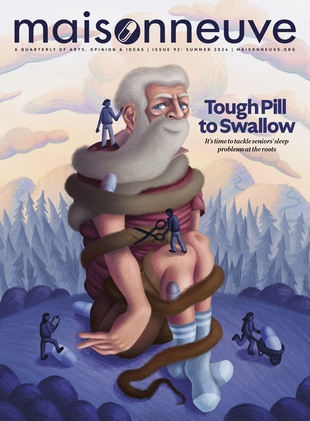

Pick up a copy of Maisonneuve's Fall 2012 issue to read Kaitlin Fontana's essay "A People's History of the Punch."

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org: