Can a Canadian Cleric Overthrow the Pakistani Political Establishment?

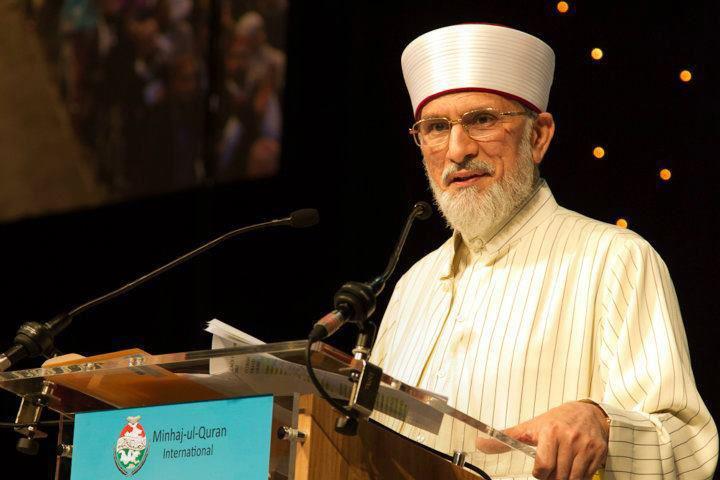

Dr. Tahir ul-Qadri speaks at a conference in 2011. Photograph by Servingislam.

In late December 2012, an obscure religious scholar and humanitarian took the stage in Lahore, pledging to overthrow the political order of his native Pakistan—such as it exists in a country where the sitting, elected government is about to complete its five-year term and possibly initiate a democratic transfer of power for the first time in the nation’s history.

Dr. Tahir ul-Qadri is a dual Canadian-Pakistani citizen and former politician who left the country after resigning from Pakistan’s national assembly in 2004 and taking up residence in the Greater Toronto Area. Upon his return, he marched with tens of thousands of people from his charity's headquarters to the capital of Islamabad, calling for the establishment of a caretaker government in advance of May elections. Estimates of his number of followers at the march vary; whatever the truth, it is surely less than the million Qadri promised, in what he styled as a Pakistani version of the Arab Spring uprisings.

The long-march masses now have their own Wikipedia entry. They settled on the capital’s main thoroughfare and listened to Qadri rail against the mukka mukka politics of money and corruption as he stood in the window of a bomb-proof shelter that Qadri referred to on Twitter as his “container.” A Pakistani news report from late January claimed that ul-Qadri’s multinational charity Minaj ul-Quran, which has branches in Toronto and dozens of other cities, purchased in November an SUV from a Dubai dealer for the journey from Lahore to Islamabad. This revelation came mmid a significant TV and billboard advertising spend, and ongoing questions about where else his money comes from, if not just supporters of Qadri's moderate brand of Sufi Islam.

He was a continent removed from his adopted home. The stock exchange reportedly moved upon his arrival in Islamabad, and entrances to the square were reportedly blocked by security to ward off suicide attackers. Qadri was acknowledged at the highest level, including by another prominent politician from the opposition, the popular former cricketer Imran Khan, who did not join Qadri's gathering. But an information minister mocked and dismissed Qadri. “You should provide your manifesto, register your party, renounce your Canadian citizenship, become eligible to run for elections, summon votes, get a 2/3rd majority, come to the assembly and then bring a change through the Constitution," he said.

Qadri did make the cover of the Pakistani edition of Newsweek: “No one actually believes that the so-called Islamabad Long March Declaration, agreed between him and the ruling coalition on Jan. 17 that helped conclude his ‘Islamic democratic revolution,’ is constitutionally enforceable. [But] Qadri’s unprecedented campout in the capital proved his organizational genius....” The New York Times nevertheless said the attention was mostly about allowing Qadri to save face and convincing his followers to disperse after four days outside. The Guardian agreed.

No word on how the view in the capital compared to that which he called, in a 2011 interview with me, his favourite view of all: Lake Ontario from the vantage point of somewhere between Mississauga and Toronto, the seat of suburban Islam in Canada.

The Islamic world is rife with populist preachers. Itinerancy in that trade is a fact of history. Consider the Turkish figure of Fethullah Gulen, who lives in self-imposed exile in Pennsylvania while commanding a multi-billion dollar educational empire that includes close links to Turkish police and the conservative ruling Justice and Development Party.

Speaking to the BBC after his occupation of Islamabad ended, Qadri denied the controversial claim that he's a puppet of the security services, which often assume the right to intervene in Pakistani democracy. The security services have ruled the scene for thirty years of Pakistani history, and might find common cause with Qadri in overthrowing the current government before its term is complete.

For whom was Qadri's revolt intended? Does the cleric give up credibility merely by joining the political fray, never mind the attention it brings his name and cause? As he first addressed the people of Lahore on December 23, southwestern Pakistan was reeling from suicide attacks. On January 10 more than a hundred people were killed in the city of Quetta, a stronghold of the Pakistani Taliban and home to many of Pakistan's minority Hazara. A banned Sunni militant group is taking credit for this latest wave. “After every killing, there are no arrests,” Muzaffar Ali Changezi, a retired Hazara engineer, told the New York Times in December. “So if the government is not supporting these killers, it must be at least protecting them. That’s the only way to explain how they operate so openly.”

When we spoke, Qadri had recently published a six-hundred-page fatwa against such attacks in general, and against the use of Islamic writings to justify them. He promised “hellfire” for those who use “jihad” to justify assaults on civilians. The families of the Quetta attack refused to bury their relatives until the government took notice, a cause that Qadri took up on Twitter—he has nearly thirty thousand followers—despite also proclaiming that the armed services were one of only two institutions in Pakistan that "perform their duties justly" (the other being the judiciary).

In mid-February, another attack hit Quetta's Shiite district, killing seventy-nine, after which locals threw stones and barricaded the streets out of grief and frustration. Human Rights Watchnotes that a culture of impunity among the armed forces and security services leaves ethnic minorities like the Hazara vulnerable to such violent campaigns, to say nothing of electoral politics in this fragile state.

The occupation of Islamabad was not Qadri’s first political intervention. Nor does this one appear finished, no matter what else happens in Pakistan before the May elections. Pakistan has bigger problems than Qadri and his backers alone can solve.