The Hijab is Not a Political Tool

My mother is the reason I began to wear the hijab. She is the strongest woman I know; intelligent, she stressed the importance of education, and most of all, faith in God. She prepped me for school speeches never accepting shyness as an excuse, insisting that her daughters speak for themselves and stand on their own. My mother wears the hijab as a fundamental part of her faith; for her it is way to carry out the Quran’s requirement of modesty and to live in accordance with the prophetic example. I too began wearing it with the sincere belief that the hijab was an act of worship; a spiritual commitment, a way of dignifying myself, and a daily reminder of my faith.

But it didn’t stay that way long. Growing up in the years following September 11th, the sudden demonization of the faith I cherish changed everything. As the war on terror unfolded before me—accompanied by the vandalism of mosques, Quran- burnings and hijab bans—I became political. The only veiled girl in many contexts, I found myself required to answer for my faith, to answer for my people (whoever that includes), and to answer for my choice to wear the hijab. I positioned myself on defense and the hijab was my banner. I excelled in school, researched my religion—finding a rich tradition of gender equality contrary to the practices of many Muslim countries and what Western commentators wished me to believe—and trained myself to speak out as a Muslim.

I politicized the hijab and that is why ten years after I first began wearing it, I decided to stop. The hijab is not my tool; it is not a banner to be flown in the face of Islamophobia, racism and xenophobia. I used the hijab as an object; a loudspeaker to say here I am, a strong Muslim woman in your midst. But though I changed people’s minds, I began to feel hollow wearing it. I was living only for other people’s eyes while totally neglecting the hijab as an element of my faith. More importantly, I felt insincere. How could I, who lost all understanding of the hijab as an act of worship fundamental to many womens’ belief, seek to represent Islam on their behalf?

Just as the hijab is not my tool, it is also not a tool for the use of the Saudi, Afghani, or Iranian orthodoxy looking to gain legitimacy by washing their States with the display of Islam. Learning of women being forced to wear the hijab or burqa disturbs me. My mother’s example and that of other hijab-wearing women I know established the hijab for me as a matter of individual choice and sincere personal conviction. Its imposition denies women essential choice in a matter of individual faith, using them as the standard bearers of a fictitious community morality. The hijab is not a dress code; it cannot be used as a pass in the litmus test of state religiosity or to shore up political support.

But just as mandating the hijab is wrong, so is banning it. The Quran requires modest dress from both men and women; it does not discriminate. But yes, centuries of patriarchy, as well as colonial rule—which created a disproportionate emphasis on personal status law and the policing of women’s dress and behaviour—have unfairly left the exigencies of modesty on the shoulders of women. The hijab as a particular form of modesty also resurged in the context of anti-colonial resistance by societies seeking to reassert an indigenous identity. While there is debate over what modest dress requires, doctrine and history have certainly made the headscarf one way of practicing that has great significance for many Muslim women.

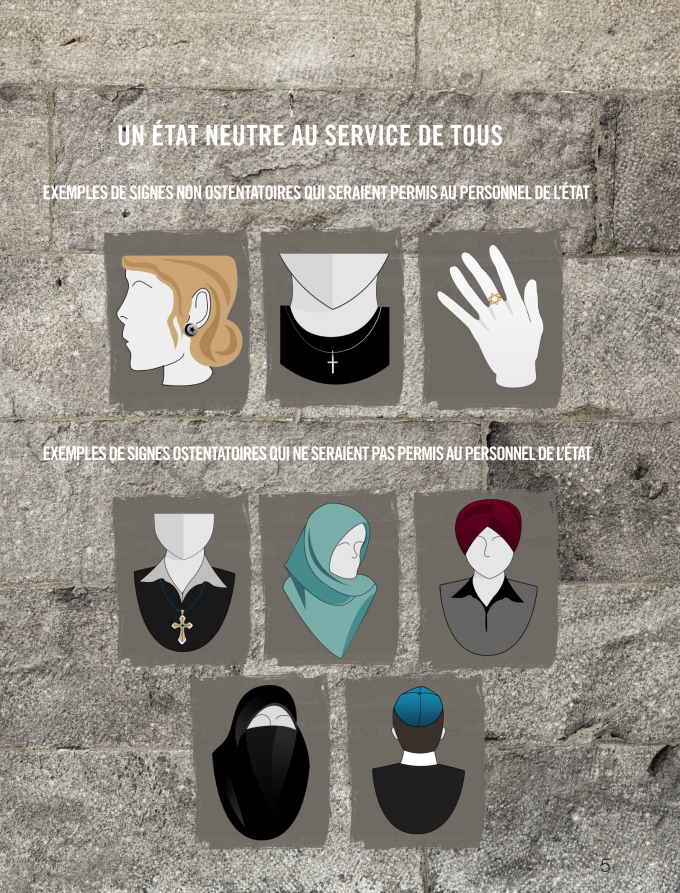

And yet, as Quebecers now grapple with the Charter of Values, the hijab is front and center, a tool used by the Parti Québécois to shore up political support. Those who would argue that the proposed Charter is not a populist measure to rally up a primarily homogenous base must account for the fact that this Charter is not rooted in any incident. No public servant has been reported for unprofessional behavior, no child indoctrinated by a schoolteacher. The Charter instead plays off an undercurrent of Islamophobia and xenophobia, prohibiting religious symbols in the public sphere, ostensibly to defend a secularism that was never endangered. A fictional problem, an unnecessary solution—but it is popular.

And just as some Muslim-majority regimes seek to build their credentials by washing the state in religion, the PQ is indeed attempting something very similar. The Charter represents an effort to wash society in secularism, a different kind of official doctrine, but no less heavy-handed. (Of course, it’s a funny kind of secularism: the crosses on Mont Royal and above the National Assembly speaker’s chair are left intact as patrimoine historique commun). Though the PQ has not proposed a total ban, the message is clear: the hijab, along with other religious symbols, is an object to be outlawed, stigmatized, removed from sight. Those who wear the hijab challenge yet another fictitious community morality: Quebec as a place without religion.

The hijab has also become a tool in the hands of one-track feminists who, ignoring the intersection of gender, race, and religion, have turned its prohibition into a cause célèbre for gender equity. Equality is an excellent ideal to strive for but politicizing the hijab in this way does not create a more equal society, just a more equal-looking one in the eyes of Charter supporters. Making men and women equal on the surface does nothing to address actual differences in power. Those seeking to truly empower women should do everything possible to open the doors to education and employment rather than create new barriers to social and economic independence.

Louise Beaudoin and other outspoken "feminist" supporters of the Charter argue that it poses no barrier to Muslim women’s employment; they will simply take the hijab off on their way to work and carry on. But to turn the hijab into an object comparable to a hat or scarf that can be left at the door in the morning with no impact on its wearer denies the fundamental, non-political, reality of what the hijab is: an act of worship that has great meaning in people’s lives. Ask someone who has taken it off: it is not easy. I went back and forth for two years before I came to my decision, all the while fearing I was losing something essential to who I am. Have no doubt: the Charter’s requirement to unveil is no small demand.

I found myself the day of the Charter’s announcement wishing I still wore the hijab. I wanted my fellow law students, hovering over their laptops following the news, to see that I—a Muslim woman and the subject of their conversation—am here, and not going anywhere. While returning to the hijab is a tempting reaction, it’s the wrong one. If I go back it will be because I have found firm spiritual grounding for my decision; not the momentary need to fight back against political attack. The hijab, along with kirpan and turban, is not an object of political expediency; I don’t get to use it that way and neither should anyone else.