Things That Make Us Muslim

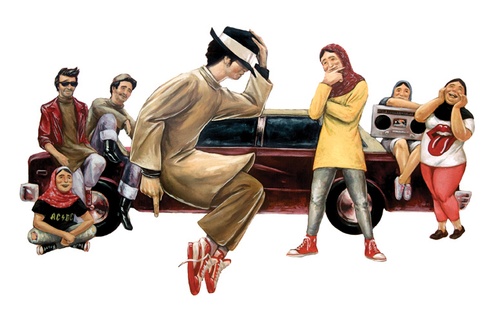

At the height of Michaelmania, everyone moonwalked—even Muslim kids in Hamilton, Ontario.

Illustration by John Perlock

At the corner of Lottridge and Barton, on a winter morning in 1977, a big girl stands next to me, waiting for the light to change. She must be on her way to Scott Park, the high school. Her arms are stiff at her sides, her hand curled around a cigarette. Why doesn’t she zip up her jacket? Right then I see the skeleton on her black t-shirt, grinning horribly and riding a motorcycle. But it has fine long finger bones and is bedecked with beautiful roses; despite my fright, I want to go on looking. A banner going across the shirt has fancy words on it:

Death to Disco.

I am floored. Who would think of making a whole shirt to talk about music you don’t like? And whose Mom on this planet would let you buy such a thing, let alone wear it?

At elementary school I frequently have bewildering moments like this. During silent reading time I occasionally look up, mystified to see the white boys in my class idly engrossed in writing LED ZEPPELIN on their jeans in blue ballpoint. I sing in the choir, I like music, but I do not understand why one band or song can possess some kids whole: defining friendships, dress codes, loyalties; sparking love, scorn, bitter arguments.

We’re squashed, four cousins, into the back seat of the family Buick, with the radio on.

Pick up the phone, I’m here alone…call me anytime…

“Oh man, this is AC/DC!” says my cousin.

“What’s AC/DC?” asks my brother.

“It means the devil,” I say, virtuously. I might have heard this at school, or else I’m just free-associating. Doesn’t the little streak of lightning—I have seen it reproduced often enough on notebook covers and denim jackets—have something to do with the devil?

“No it doesn’t, stupid! AC/DC means different types of electrical charges! You need electrical power to play guitar really loud. It’s a cool name.”

I am silenced by my older cousin’s superior knowledge. I concentrate on the words of the song, which seem to be telling a story I cannot make out. I know what TNT is, of course, from watching Road Runner. But where is the singer, and why is he there alone? What is enough to drive you nuts? I’ve heard other songs on the radio that make me intensely curious to know the full story, like the women who sing about a mama who cried on the phone, wanting her girl to come home (why won’t she?) or the man who sent someone named Mandy away, and he needs her today (then why did he send her away?). But there is no one to ask, and no more time: it’s a Saturday morning, and we’ve arrived at Islamic school. The radio is turned off. We pile out of the car, head into the building and up to the second floor.

In 1975 a polyglot assortment of Muslim families decide to pool their efforts to teach their children the basics of Islam, its history, and to read and recite the Quran in its classical Arabic. The Hamilton Board of Education helps out, giving the group permission to use space in various schools around the city from year to year.

Our early religious education consists of stories of the prophets, memorizing the Quran, and lots of singing; the adults agree that reciting the Quran in Arabic is of primary importance. But everything else, everything to do with being Muslim, we are taught in English. We sing “The Lord Told Noah” with great vigour, acting out memorable lines like elephants and kangaroozies roozies. On bus trips to anywhere we love the call-and-response cheers “We Are The Muslimeen” and “Shout Like Thunder (Allahu Akbar).”

Did the snow that our parents encountered when they arrived in Canada bury their personal memories under its great blank drifts? Where were the singers and street snacks and great cinematic moments of the cities they came from? Instead, they reached for the corresponding blankness of the Arabian desert; for an imagined, pristine, seventh-century Islam. Or was it the forms of Christianness visible here that provoked their reply of collective Muslimness? The orderly grey city blocks, the church bells that rang out on the hour, the recitation of Our Father in school every morning—could these things have prompted our parents to insist on their children’s nightly recitations of Sura Fatiha; on taping straight lines across the white sheets spread on the floors of rented gyms, for Eid prayers?

North America gives us our Muslimness, bright and new and light as air. Young as we are, unencumbered by history or politics, we have only vague notions of Islam as a grand, centuries-old civilization, and no anxieties about cultural authenticity. Not knowing that we lack our parents’ lived histories gives us a brash kind of freedom, if it doesn’t quite make us brash. Hastily torn notepaper and markers are all we need to turn a space “Islamic,” pointing men in one direction and women in the other. We craft stickers and posters, mottos on t-shirts painted with glitter, bumper stickers and buttons. We work long finger-cramping hours assembling poems and cartoon drawings into newsletters or zines, photocopying, stapling and mass-mailing them to other teens. We make it up as we go along.

On a hot summer day in my teens I spot my younger brother and his friends in the parking lot of the Hamilton mosque, practicing the moonwalk. Behind the cars no one can see them—an older sister doesn’t count—so they shrug and flow with expertise, the rasp of their sneakers on the gravel raising puffs of dust around their ankles.

I’m impressed with my younger brother’s skills; maybe a little envious. I have not waded happily into being a teen. Partly I’m at a disadvantage in being younger than my classmates, with their incomprehensible enthusiasm for slow dances and first kisses. Partly, too, I’m inhibited by the adults in my life; their continual warnings make adolescence seem disreputable, fraught with potential danger. “Teenagers” have zero interest in your religious holiday or the language your grandmother speaks. “Teenagers” fall into all kinds of temptations and disasters; they can even die, like Anonymous in Go Ask Alice, of a tragic drug overdose.

These dangers loom especially large at any mention of rock music after Yusuf Islam speaks to a Muslim audience in Ontario in the early eighties. He sings a children’s song called “A is for Allah,” then chides us, “We don’t…clap…for Muslims.”

Here is a stern new religious authority who enthrallingly, inexplicably, used to be a rock star. Soon after his lecture, my mother brings home some secondhand Cat Stevens records. We pore over the album covers and lyrics as if they might contain some clue to link the music to being Muslim, or reveal why he decided to reject his music career. We find nothing, other than the song “Peace Train,” which is now an unofficial anthem for the Islamic conversion experience.

Oh peace train, take this country, come take me home again.

Our parents, as newly arrived outsiders with young children, crave conversion stories. Converts draw large, fascinated audiences at the Islamic conferences. No one dreams of challenging their religious opinions; their stories matter too much in a secular culture where Muslimness remains almost completely invisible.

Fortunately, Thriller is released in 1983. It makes music as a cultural phenomenon suddenly intelligible not only to Muslim kids but also, crucially, to our parents, who stop whatever they’re doing to watch the “Billie Jean” video with us every time it comes on. Somehow, when we watch Michael dance, everything about pop that had seemed previously inaccessible becomes ours. To see him at the same time as millions of other people, to react with the same pleasure and awe, is at once to become part of the same culture, and to begin to feel a certain confidence in our own tastes, our own creative potential.

This confidence has to do with the fact that Michael Jackson is an African-American. As religious teachers and imams, black American men were unquestioned authorities in our eyes: they were the funniest, the coolest, the most engaging role models we had. We liked their easy, friendly style of talk, so different from our parents. They were highly sought after as public speakers; their sermons and lectures eagerly attended, often tape-recorded and passed around among teenagers. Kids who were reluctant to talk to their own parents could talk to the imams.

The imams start mentioning Michael Jackson in their sermons as a prime example of The Challenges Facing Muslim Youth in the West. They smile as if they’ve found us out, teasing us for being in thrall to frivolous secular culture. There is no question in their sermons of anything so harsh as the prohibition of music. The truth is that Michael Jackson gives the imams a toehold on popular culture, too. They say his name, and their talk has a sharper edge. Pop, that dazzling strobe light, emitting all our anxious fever-dreams of what the future might contain, has overtaken us. It can no longer be completely kept out, even from the sheltered places where we pray, where we try to express the things that make us Muslim.

Ramadan is a familiar event now, widely appreciated in a way it wasn’t when I was a girl. People are avid for its traditional stories and lavish, painstakingly prepared meals. They want its romance: moonlight over desert dunes; ‘oud and camel bells, the call of the muezzin from the minaret. They want the sweet garlicky fragrance of the roasted lamb and the wisp of the saffron releasing its perfume into the venerable grandmother’s cup.

But in this industrial city, when I was in my teens, Ramadan arrived in the summertime, in view of smokestacks, within earshot of church bells and the amplified voice of the sports commentator at Ivor Wynne Stadium. The days of fasting were intensely sunny, long and hot. I had no responsibilities and no idea when or how my life would begin. What are the things I craved when I fasted? The products of the fairground, the dime store, the truck stop with the sun beating down on the hood of the family Buick. Popsicles. My cousins liked the Astro Pops that came in red, white and blue stripes, in the shape of a rocket on a wooden stick; I liked grape. And orange. And fudge. Fudge popsicles, slushy drinks, ice cream sundaes with chocolate sauce and chopped nuts. I longed for hamburgers with relish and mustard, or fried chicken, for fries doused in ketchup and vinegar from a shack near the beach on Lakeshore Drive, popcorn in red-and-white-striped bags, sour candies puckering my mouth with the taste of grapes or green apples.

The sublime quality of these cravings derived from their being impossible to satisfy. Sunset was so late in the evening that the dime store and the fast food shack on the beach were out of reach; we usually opened our fast at the mosque. By the time we had eaten our dates and drunk water out of Styrofoam cups and performed maghrib (sunset) prayers, what appealed to me were not the platters of rice pilaf and baked chicken that vied for space on the communal dining tables with the stacks of naan wrapped in tinfoil and pots full of ground beef curry studded with peas and potatoes. Not samosas or salad or the dozen doughnuts someone unfailingly brought to every single Muslim gathering. I wanted only watermelon, sliced into cool pink triangles. And then sleep.

Maha and Maliha, friends of mine in Brampton, know an Urdu nasheed which I beg them to sing repeatedly at Muslim Youth of North America gatherings, because I have never heard anything quite like that minor-key, haunting harmony. (It is when we girls are by ourselves that we sing aloud; generally, only the boys perform in mixed audiences).

The nasheed evokes some feeling that I ought to have heard it before—some hint of a whole world of music as familiar to me as Urdu itself, one I’ve narrowly missed. That feeling comes back to me a few years later at university, when a group of us Muslim women go out to watch The Last Temptation of Christ. During the scene of the Last Supper, excited whispering breaks out in the row of scarfheads near the back of the cinema.

—Did you hear that? It sounds like the azaan!

—I heard ‘La illaha il Allah’!

—So did I!

It is the soaring voice of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, singing the Islamic call to prayer. After watching the film I promptly go out and buy the Passion soundtrack and the accompanying Passion—Sources collection, on cassettes. The world opens: Punjabi qawwali, Egyptian fallah and Moroccan gnawa—music I have never heard, despite the fact that my closest friends are of Pakistani, Egyptian and Moroccan origins. I can thank an Italian-American director’s exploration of his Christian beliefs for teaching me that Muslims have been making brilliant music for centuries.

On highways that take us from Toronto to Detroit, from Indianapolis to Chicago, we stop at gas stations and strip malls for prayers and packs of gum; in our jeans, scarves and bomber jackets our family backgrounds are invisible, irrelevant. The languages we speak are barely audible, except for the occasional Urdu or Arabic word, dropped into the flow of our conversations as an affectionate gesture, or an inside joke.

Road trips always start with recitations of the Quran, of course, to pray for a safe journey. Once the van or bus hits maximum speed on the highway we call for favourite songs to be sung: “Running to Stand Still” by U2; “Mercy Street” by Peter Gabriel. A devoted metal girl teaches us the chorus of a plaintive, wistful ballad by Mötley Crüe, changing the lyrics only a little to make romantic longing sound religious. Hibba and Fatima perform a rap they have written themselves, enchanting us with the swinging, effortless rhythm of their soft, savvy voices, one chiming in over the other.

Islam is joy

Islam is fun

Islam means peace for everyone!

One sleepy winter afternoon aboard another school bus, en route to an Islamic bookstore in Indianapolis, an unassuming girl from Boston delivers a judiciously throaty performance of Whitney Houston’s “The Greatest Love of All.”

“That’s called vibrato,” she explains patiently, over whistles and cheers (masha’Allah!) and the drone of the windshield wipers. “My voice is just naturally like that.”

See the rest of Issue 36 (Summer 2010).

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—Muslim Sex

—From Islamabad to the Swat Valley

—The Controversy Entrepreneurs

Subscribe to Maisonneuve — Follow Maisy on Twitter — Like Maisy on Facebook