A Disillusioned Defence of Obama

In 1967, the Partisan Review published a symposium by sixteen public intellectuals called "What is Happening in America?" The editors began by stating, “There is a good deal of anxiety about the direction of American life. In fact, there is real reason to fear that America may be entering a moral and political crisis,” and proceeded to ask the participants seven questions, beginning with this one: “Does it matter who is in the White House? Or is there something in our system which would force any President to act as [then-president Lyndon B.] Johnson is acting?”

The response was virtually unanimous: “Our whole history as a nation shows that it matters tremendously who is in the White House”; “Yes, nothing could matter more than who is in the White House”; “Of course it matters who is President”; “Does it matter who is in the White House? Of course it does.”

Like Johnson, Barack Obama has been perpetually badgered by his first and most enthusiastic fans. We have whined about the half-baked results of his basic promises—the partial withdrawal of troops from Iraq, for instance, or the half-trillion dollar subsidy to health insurance corporations mandated by Obamacare—and jeered and wailed with each concession to the GOP, each whistleblown revelation and unanticipated military action. “Judas!” we cry.

And not without reason. His administration immediately ramped up the war in Afghanistan. It has increased foreign drone attacks sixfold. Year over year, it has deported nearly twice as many undocumented immigrants as its predecessor. It has condoned extra-judicial executions of U.S. citizens. It has expanded the domestic security networks that have nullified core civil liberties. Why is this happening? Well, says leftwing journalist Chris Hedges, “Obama is seduced by power and prestige and is more interested in courting the corporate rich than in saving the disenfranchised.”

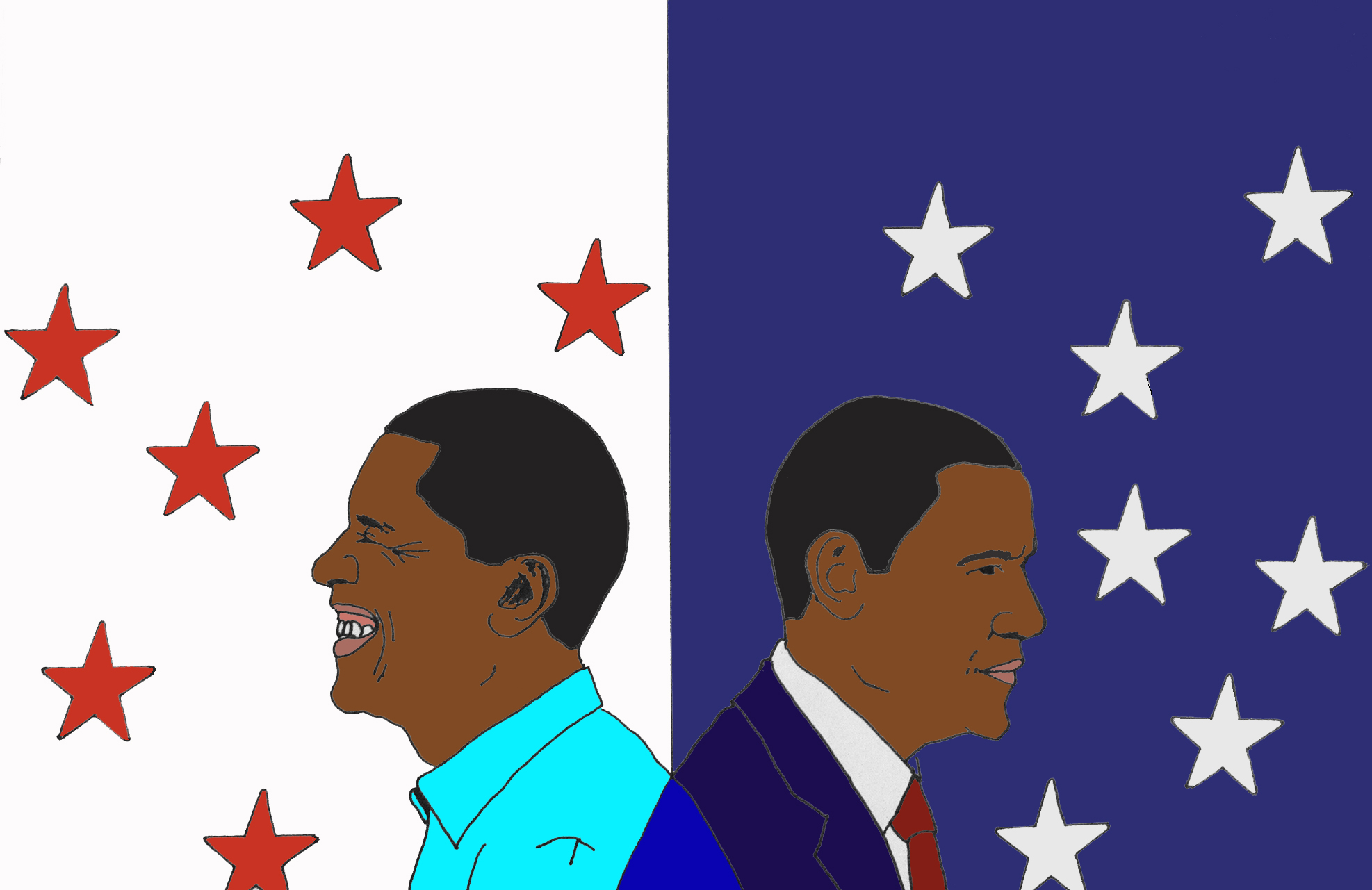

Attempts to divine the content of Obama’s soul by examining his policy moves have become a kind of sport for the liberal blogosphere. But what these suppositions overlook is the sincere commitment to radical reform that is conveyed in Obama’s own writing. There is a schizophrenic disconnect between Hedges’ caricature on the one hand, and on the other, the figure that emerges from Obama’s 1995 memoir, Dreams From My Father. A sensitive and thoughtful examination of what it means to be black in America, the book discusses concepts of “class solidarity” and “white capitalist imperialism” without discomfort or derision, explains why Malcolm X has been a central role model for him and describes Obama's three years as a low-paid community organizer in some of Chicago’s poorest neighbourhoods, guided by the sincere belief that “change won’t come from the top...[but] from a mobilized grass roots.”

Likewise overlooked is Obama’s more recent children’s book, Of Thee I Sing: A Letter to My Daughters, which profiles thirteen American figures including Cesar Chavez, Sitting Bull, Jane Addams, Martin Luther King Jr. and Georgia O’Keefe. What comes through in Obama’s writing is the same set of ideals found almost exclusively among self-identified radicals.

Few outside the milieu of white supremacists and New-World-Order paranoiacs have argued that Obama is truly evil at heart. Rather, the most compelling explanation, certainly the most popular one, for the chronic crises of his presidency is that he is constantly showing up to the gunfight with an olive branch, that he is “not cut out for politics”—that he does not have what it takes to lead the country in the promised direction of hope and change. Wrote Thomas Frank after Obama’s second inauguration: “The president is a man whose every instinct is conciliatory. He is not merely a casual seeker of bipartisan consensus; he is an intellectually committed believer in it. He simply cannot imagine a dispute in which one antagonist is right and the other is wrong.”

Time and again, we have demanded that the president demonstrate some self-respect and draw a line in the sand against the knuckle-dragging barbarians in the GOP. Well, that is precisely what he did last month, and the result was a government shutdown that may ultimately play into the now-longstanding conservative tactic of making Washington so dysfunctional as to demoralize public faith. In The Audacity of Hope Obama responds directly to the growing calls among liberals to replicate Republican tactics of winning elections by cheaply vilifying opponents and exploiting hot-button issues, and I think he is probably correct when he writes “it is such doctrinaire thinking and stark partisanship that have turned Americans off of politics.” The chaos wrought by the shutdown and other such misadventures, he adds, “is not a problem for the right; a polarized electorate—or one that dismisses both parties because of the nasty, dishonest tone of the debate—works perfectly well for those who seek to chip away at the very idea of government.”

The line-in-the-sand camp also fails to acknowledge that Obama never would have had a shot at the presidency were it not for his consensus-building rhetoric. It is precisely that which has distinguished him from every best attempt by the Republicans to take him down; it’s hard for a crowd to cheer at the message of some Randian nerd like Bobby Jindal or Paul Ryan or Marco Rubio telling the country that it should be more divided rather than more united, or Sarah Palin’s vague assertions that government cannot be an agent of positive change. For many in 2008, it was Obama’s apparent faith in the system that inspired them.

The question remains, however: has the Beltway turned this patriotic idealist into a sociopathic political automaton? Several have suggested that this is so by pointing to his foreign policy—a portfolio in which the President’s power is, legally speaking, second to none. That Obama has overseen escalations of military activity in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia and Libya proves, they say, that he is, alas, “a hawk.” It’s difficult to reconcile the community organizer and children’s book author with the man who regularly sits down with the CIA and personally orders them to bomb this or that target, resulting in deaths that now number well into the thousands. It is not hard to argue that he has blood on his hands.

But we cannot pretend that such behaviour is unique or unprecedented. Of the sixteen essays in the Partisan Review symposium, by far the most compelling is by Susan Sontag, who focused on the president’s acts of war: “I do not think that Johnson is forced by ‘our system’ to act as he is acting: for instance, in Vietnam, where each evening he personally chooses the bombing targets for the next day’s missions.” Nearly half a century after that essay was written, it is perhaps time we stopped wondering why every seemingly kind-hearted, fatherly fellow elected to the Oval Office has turned out to be a bloodthirsty maniac. Though it was already incipient in Sontag’s time, it is clear today that the U.S. has risen to the unique role of financial and military guarantor of global capitalism, and that seems to mean that beyond free trade agreements, its foreign policy can only consist of bombing a little or bombing a lot.

Likewise, in the domestic sphere, it is clear that there are systemic reasons for the failure of idealists in American government. As though attempting to excuse his future disappointments, Obama chose to dedicate a full chapter in Audacity to this problem. Government has been associated with dirty hands for as long as it has existed, but, he asks, “What happened to make these men and women appear as the grim, uncompromising, insincere and occasionally mean characters that populate our nightly news?” Tellingly, his response has to do with his first-hand experience of asking for major donations to finance political campaigns:

"Increasingly I found myself spending time with people of means—law firm partners and investment bankers, hedge fund managers and venture capitalists. As a rule, they were smart, interesting people, knowledgeable about public policy, liberal in their politics, expecting nothing more than a hearing of their opinions in exchange for their checks. But they reflected, almost uniformly, the perspectives of their class: the top 1 percent or so of the income scale that can afford to write a $2,000 check to a political candidate. They believed in the free market and an educational meritocracy; they found it hard to imagine that there might be any social ill that could not be cured by a high SAT score. They had no patience with protectionism, found unions troublesome, and were not particularly sympathetic to those whose lives were upended by the movements of global capital. …I know that as a consequence of my fund-raising I became more like the wealthy donors I met, in the very particular sense that I spent more and more of my time above the fray, outside the world of immediate hunger, disappointment, fear, irrationality, and frequent hardship of the other 99 percent of the population—that is, the people I’d entered public life to serve. And in one fashion or another, I suspect this is true for every senator."

Equally indicative of Washington’s structural brokenness is the fact that voting districts have been so aggressively gerrymandered that the Democrats enter every election cycle with an automatic statistical disadvantage. Few have even complained about the fact that in last November’s federal election, the Democrats won 48.3 percent of the popular vote for the House of Representatives, over the GOP’s 46.9 percent, and yet the latter walked away with 54 percent of the seats. (“It’s not a stretch to say that most voters no longer choose their representatives; instead, representatives choose their voters,” wrote Obama in Audacity.)

Fixing these sorts of issues would be a modest start. Still other, more insidious forms of bribery infect Washington; since the time of Reagan, corporate lobbies have exploded. (See “The Mystery of the Free Lunch,” Michael Kinsley’s 1981 New Republic masterpiece, in which he avers that the Reagan administration made it acceptable to drink champagne in limousines again.)

Most on the left are aware of all this. Writing in the twilight of the Bush era, Thomas Frank himself argued out that for the previous eight years, right-wing think tanks and corporations, working hand in glove with the Republicans, had fundamentally restructured the capital. “They have made a cult of outsourcing and privatizing,” he wrote, “they have wrecked established federal operations because they disagree with them, and they have deliberately piled up an Everest of debt in order to force the government into crisis. The ruination they have wrought has been thorough; it has been a professional job. Repairing it will require years of political action.”

Bush certainly opened the floodgates of corporate interests in Washington, and at times Obama has appeared to successfully stanch that flow, if only by a fraction. (His administration’s new restrictions on lobbying, for instance, have led to a sharp 28 percent drop in total cash being spent by lobbies.) At other times, however, it seems he has merely been swimming against an overwhelming current—and the Supreme Court’s 2010 ruling in the Citizens United case is a case in point.

So it is not totally insignificant who occupies the Oval Office. But these problems are structural, and the vast majority of the criticisms directed at Obama from the left have rested on the naïve and discredited assumption that democracy still exists in America. That so many dimensions of American government and social structure have gotten palpably worse under the tenure of the most intelligent and compassionate president America may ever see ought to tell the American left, looking ahead, that it needs to think big—at least as big as Occupy thought, but better organized and more patient. Part of the reason we have continuned to focused so much attention on Obama is that it is sometimes difficult to imagine a movement of that scope. But an equally big part of the reason that we have been screaming so loudly at him is that he is the only one who may actually listen to us. There is a certain logic to that—in the short run, it may even mean that we should scream as loud as possible—but in the long run that will only go so far.