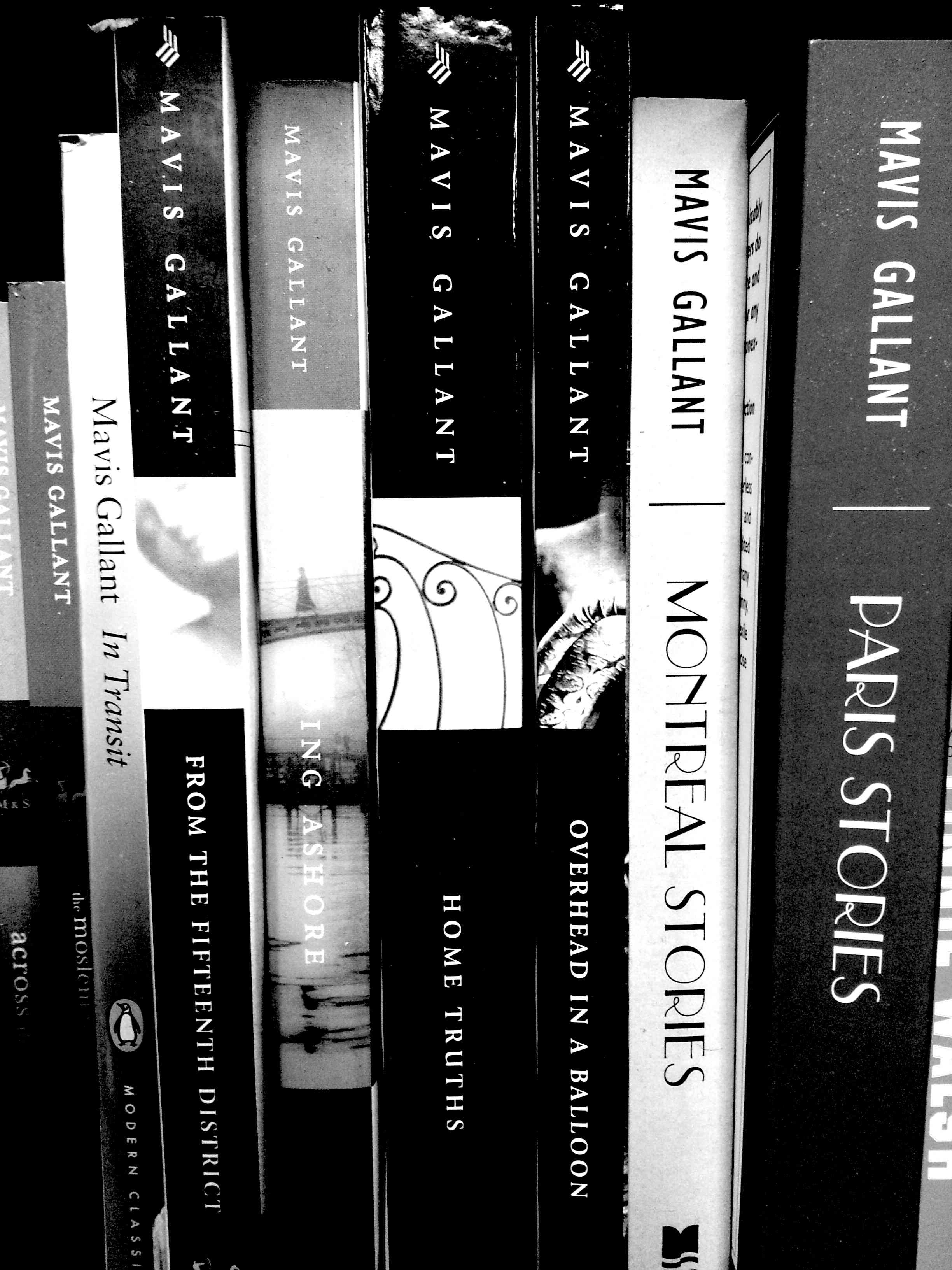

Mavis Gallant: A Love Letter

Dear Mavis Gallant,

I discovered you only two years ago, unusually late for a student of literature, as a teaching assistant to a professor who just happened to champion the Canadian short story above all other forms—a rare breed among academics, especially Canadian ones. This professor was special for other reasons. Miniature golden spectacles balanced precariously on his nose, seemingly without function. He lamented the fact that his students were no longer forced to learn God Save the Queen by heart. But to me he was unique most of all for this unabashed, nationalistic, literary pride. You see, I had somehow come out of my undergrad harbouring a distinct suspicion (and even disdain!) of Canadian fiction. The professors I most admired were Americanists, bespectacled by the more fashionable dark rims of serious, modern people everywhere. They told me the ex-pats to read were Hemingway, Stein, Joyce, Fitzgerald, and Pound. While I attempted to figure out what kind of literature I was going to make a career out of, no one ever whispered “Gallant!”

Now, I know you don’t particularly like academics and think that they treat stories with the same delicate touch as the extraction of crude ore from the earth. But hear me out.

On the occasion of reading your stories for the first time, I was experiencing my own micro-alienation as an Albertan living in Quebec. My heart swelled with recognition as you described Canadians, Americans, Austrians and Italians living in France or Spain, even though I had not yet visited those countries myself. There was something in your smallest details that seemed to capture the exact life my friends and I were living in Montreal—members of a tight, sometimes claustrophobic, community of Anglophones in a Francophone city that could care less if we lived or died amongst them. The daily insecurities of a life of chosen displacement were beginning to wear on me, and though I wasn’t technically an ex-pat, I latched onto your stories of other, more realistic ex-pats as if you had thrown me a life preserver in the middle of the ocean.

Maybe I’m being overdramatic. I was so taken with you that I made my students cookies for their tutorial on the day we were to discuss "The Moslem Wife." I told them that good literature should always be paired with good food and by that logic, if I kept reading your stories, I would soon be very fat. Instead of talking about "The Moslem Wife," we listened to you totally dominate Megan Williams in an interview on the CBC.

The professor with the golden spectacles said a lot of nice things about your work. He (and I, for that matter) love the way you describe sex as basically a union of genitals. He said that, like Munro, you also problematized the narrative of the “beloved” except that you did it better. I agree and so I know you wouldn’t be keen on the idea of a love letter in which you, of all people, are featured as the beloved. So let me make it easy for you. The romance between author and reader is always a troubled one, after all.

My love for you is probably born out of a selfish desire for some universal recognition of my own unique experience of exile. It was nice to think that, like the characters in your stories, exiles could be elegant and interesting—not perfect, no, but worthy of being immortalized in fiction. For a while, your stories gave me a strange sense of purpose, evidence that the life I had chosen for myself in Quebec might be worthy of its own story. So, I was besotted—with you, of course, but also with myself. After all, it was you who taught me that the business of love is ultimately egocentric. And I’ll probably never read all of your stories or think about you very often, after this. But it will continue to remain remarkable to me that a woman who lived most of her life outside of Canada is the same woman who so precisely described what it meant to be Canadian. For me, it was never the unnerving small-town lives of Munro, or the gothic forests of Atwood that sparked a sense of nationalist recognition. It was your displaced strangers forming communities in entirely non-Canadian settings, discovering and structuring their own identities through difference, that made me go, “Oh, [I get it!] Canada.”

For that, I am sincerely grateful.

R.I.P Mavis Gallant