Archaeology of the Digital: Media and Machines

At first glance, it’s difficult to understand the disparate pieces of the Canadian Centre for Architecture’s new exhibit, Archaeology of the Digital: Media and Machines. The assortment of artifacts, films, whirring machinery and 3D imaging seems anything but a cohesive whole.

The second installment of an ongoing series, Media and Machines brings together architectural experiments in computation from the mid-1990s to the early twenty-first century. Each project is given its own room, and though an overarching theme isn’t immediately apparent, the work is treated with respect and lovingly showcased.

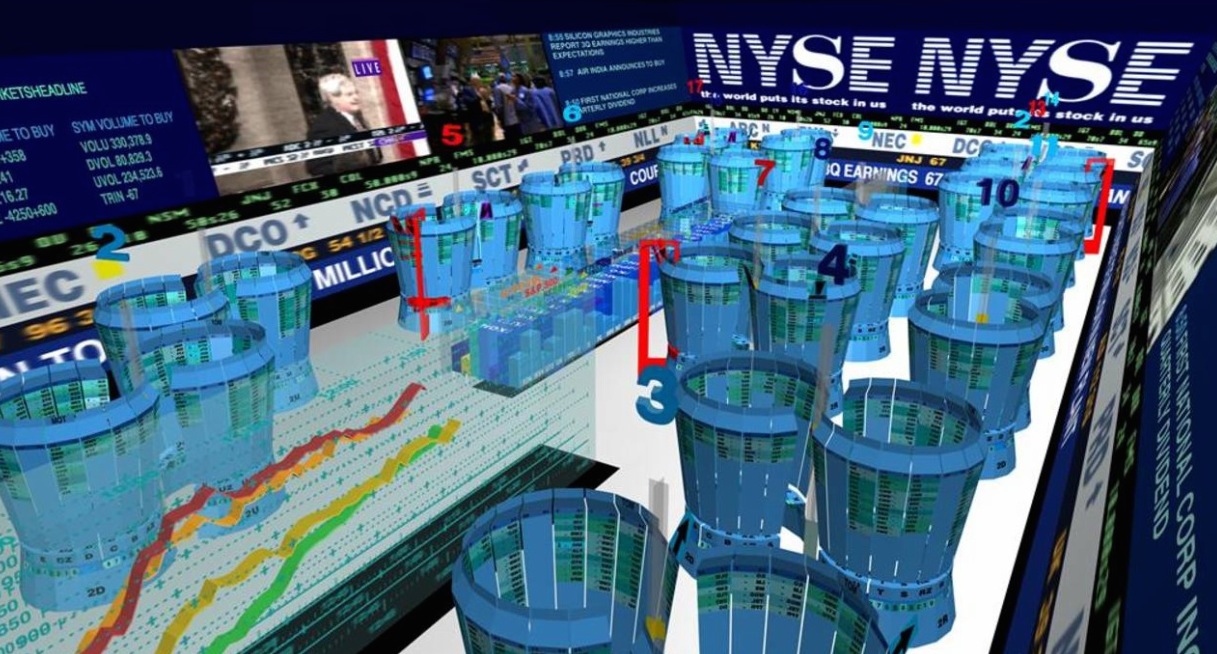

The first gallery, the one welcoming visitors, houses the New York Stock Exchange Virtual Trading Floor, a work commissioned by the NYSE from Asymptote Architecture’s Lise Anne Couture and Hani Rashid. Designed between 1997 and 1999, the project sought to digitize the NYSE, building on the existing physical structure of its trading floor to create a real-time infographical tool for tracking stock prices, detecting suspicious activity, and predicting future crashes. The Virtual Trading Floor, inspired by the stock exchange’s dynamic, “maniacal” feel, augments its physical counterpart, and was, according to its creators, instrumental in allowing the stock exchange to reopen a mere four days after the September 11 crashes.

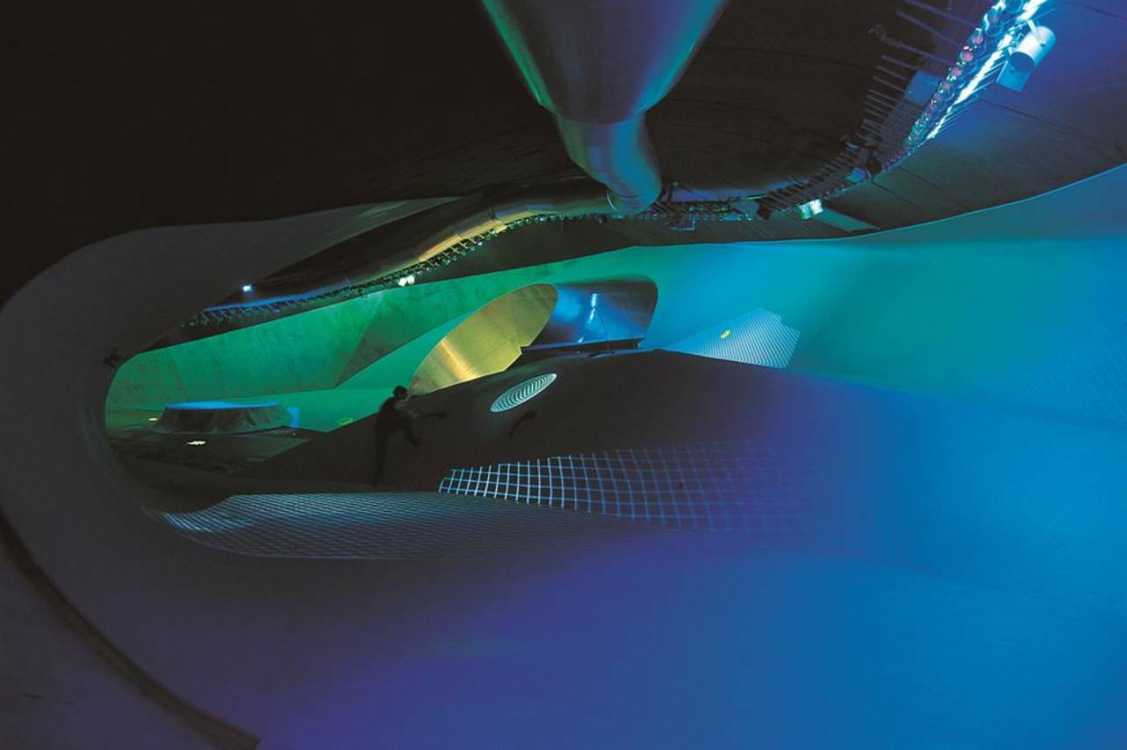

A radical change in tone occurs in the next room, where Lars Spuybroek’s H2Oexpo is presented. A visitors’ pavilion in southwestern Holland, for much of the 1990s H2Oexpo shepherded hundreds of thousands of visitors through an immersive, surreal experience like something grown from Gaudi’s DNA. The building used interactive sound, lighting, and sloping planes as an abstract representation of fresh water.

Throwing away traditional concepts of space and movement, Spuybroek designed not for repetition—the way one would attempt to make daily kitchen tasks as painless as possible, for example—but for the experience. In this respect, the rest of the exhibit certainly delivers. From Karl Chu’s ominously titled Catastrophe Machine (an automated drafting table used to represent mathematical principles) to the footage of the NSA Muscle, a pneumatic room that, able to constantly change its shape, was built in 2003 for the Centre Pompidou, the physicality of these computer-generated projects is on display.

HypoSurface, designed by Mark Goulthorpe of dECOi Architects, has perhaps the most obvious presence, if one goes simply by the amount of noise generated. The project, a “skin” made up of pixel-like metallic facets that takes up an entire wall to itself, is operated by a series of pistons, allowing the facets to create patterns, spell words, or move in time with musical performances. Modified for exhibition at the CCA, HypoSurface manages to draw its audience in, a task in which other projects, unable to be fully recreated, unfortunately fall short.

But if the exhibit poses a challenge for the viewer, the curatorial team was also pushed out of its comfort zone, with CCA director Mirko Zardini calling the entire process “a learning experience.” In an effort to present the materials native to when they were designed, out of date technology was used. In fact, the projects in this installment were chosen, according to curator Greg Lynn, specifically for being the most difficult to represent.

Despite the numerous tablets set up throughout the exhibit, Media and Machines seems frozen in the past, a veritable time capsule. One project, Panneaux Objectile, though beautiful, seems unremarkable. But Bernard Cache’s custom, digitally designed wall panels are only unexceptional by today’s standards. Though now a staple of hotel lobbies and public buildings, it was Cache’s original textured work that set the tone, showing an impressive prescience for design trends and their marketability. Cache had, long before such things were common, a website allowing visitors to create and purchase their own panels, a touch of modern-day DIY in a decidedly MySpace age. “If you consider the square meters produced by all the copies of panels that have been made,” says a highlighted quote, “I think we probably are the digital architects who built the biggest amount of square meters, thanks to all the companies that copied us.” The historical importance of Media and Machines is ever-present.

The exhibit’s primary function, then, is decidedly archival. Catastrophe Machine had to be rebuilt specifically for the exhibit, the originals having been lost. Calling it a resurrection, a fitting description that points to the difficulties of safeguarding this work, all that remains of Chu’s original tables is a series of small photographs. Zardini, for his part, writes that “this ensemble of projects forced the CCA to address both technical and critical issues regarding archival and exhibition practices.” The collection challenged the centre’s ability to accommodate new forms of media, and the inclusion of details like digital file names on the works’ title cards stresses the importance of the source material; the “.mov” is clearly of interest, if only to those involved in preserving these pieces for posterity.

The centre—celebrating its twenty-fifth anniversary this year—seems bent on meeting this task head on. The exhibit is advertised as an attempt to “critically investigate the development and use of digital design tools,” and Lynn’s attempt to show the expanding definition of architecture seems evident. The exhibit creates a compelling window into a period of time when digital media radically changed the face of architecture.

Archaeology of the Digital: Media and Machines runs until October 5, 2014.