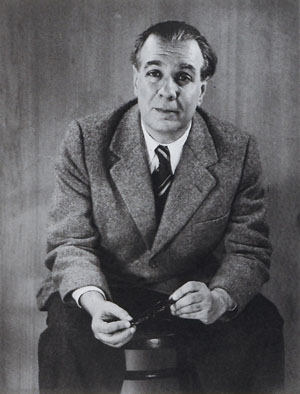

Borges & I Watching the World Cup

Jorge Luis Borges, arguably Argentina’s most famous writer, hated soccer. Like many intellectuals, he feared the blind emotional fervour that fuels nationalism and is co-opted by political leaders. As Shaj Matthew writes in the New Republic, Borges witnessed fascism, anti-Semitism and Peronism take hold of the popular imagination in Argentina. So, understandably, he was suspicious of the Latin American religion of the masses: soccer.

Like Borges, I’ve always distrusted sports fan culture. I get nervous when crowds start yelling in unison, chanting or singing slogans. Whether in a stadium or at a political rally, I get a little claustrophobic. Is this because I’m Jewish? Did my childhood exposure to Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will ruin me for the delights of mass spectacles? Or is it because, as a left-wing intellectual, I view nationalism as an empty form of fictional identity that usually supports the war-mongering elite?

Whatever the reason, I’ve always counter-identified with sports. Chess? Yes. Avant-garde jazz? Yes. High-fiving over sports? Not likely. As the hooligans yelled and screamed over meaningless goals, I was sitting in the corner reading Borges’ essays on Jewish mysticism.

Borges hated football, but let’s not forget that he also hated being Jorge Luis Borges, Argentina’s most famous writer. Borges gave a lecture in Buenos Aires at the exact moment that Argentina played its first game in the 1978 World Cup. Argentina, hosting the tournament, had recently suffered a military coup and begun the infamous Dirty War that would “disappear” tens of thousands of its own civilians.

Borges took this moment—where the spectacle of soccer served to distract the world from the crimes of Argentina’s military dictatorship—to present a lecture on immortality. Faced with the idea of immortality, and in the last decade of his life, he said:

“It would be frightening to know that I am going to continue, frightening to think that I am going to go on being Borges. I am tired of myself, of my name, and of my fame, and I want to free myself from all that.”

Rather than using the opportunity to expose the myth of nationalism, Borges lectured on one of his longest lasting themes: the fiction of personal identity. “I propose to prove that personality is a mirage maintained by conceit and custom,” he writes in the 1922 essay “The Nothingness of Personality.” In “Everything and Nothing,” Borges says of Shakespeare: “there was no one inside him; behind his face and his worlds there was no more than a slight chill, a dream someone had failed to dream.” In “Borges and I,” the writer speaks of how his life has slowly been appropriated by “Borges” the famous author. The piece concludes: “I am not sure which of us it is that’s writing this page.” Borges suggests that our very identities are merely stories that we tell ourselves, costumes we wear. And he doesn’t want to wear the same costume forever.

Borges’ 1978 lecture continues:

“We could say that immortality is necessary—not the personal, but this other immortality. For example, each time that someone loves an enemy, the immortality of Christ appears. In that moment he is Christ.”

This is the mystical form of immortality that Borges advocates in 1978: a complete dissolution of identity, up to the point of loving one’s enemy. Not an easy task for either a soccer fan or a left-wing intellectual.

But here is where Borges and I part ways: I find something about the joy of watching soccer that confirms this mystical dissolution of identity. Beneath the nationalist and political identifications that divide teams into good versus evil, there is o jogo bonito: the beautiful game.

As Borges knew too well, once you’ve lived a life, you start to get tired of yourself. Don’t get me wrong, it is lovely to be a person. It’s nice to have habits, routines, likes and dislikes. But for how long can you listen to the same music? For how long can you have the same favourite colour? And for how long can you dislike something that you’ve never really experienced? So I started watching the World Cup. As an anthropological experiment, I watched other fans, I borrowed their excitement. I emulated their gestures, picked up their expressions. I was undercover—in sports drag.

But over time pretense becomes reality and our costumes turn into our identities. Four World Cups later, I have to admit to myself that I’ve become a fan.

At a party a few nights ago, I sought out the other soccer fans and found myself gesticulating wildly over the horizontal flash of Mexican keeper Guillermo Ochoa’s glorious save against Brazil. When Chile beat Spain and kicked the ex-imperial power out of Latin America, I leapt to my feet in excitement. In that immediate physical reaction, I realized that the passion for soccer has entered my unconscious. Have I become a sports hooligan?

Being immune to nationalism, I found another avenue: historical injustice and the promise of retribution. So I become joyous when Latin American teams send home the European colonial powers. I prayed for Algeria to beat Germany—not just because of the Holocaust (I’m kind of over that), but so that Algeria would, finally, meet France in the post-colonial match up of the century!

As a “left-wing intellectual,” I identify one team as representative of the good, the true, the just—while viewing the other side as imperialist, colonizer, scum-bag. And I derive emotional reward from identifying with—guess who—the righteous. I was furious, in 2010, when the Uruguayan Luis Suarez stole victory from Ghana with a handball. But I loved Uruguay for sending England home in 2014. As a Jew, I will always root against Germany (I was just kidding earlier; I’m not over it). I’ve thrown myself into the passion, joy and fury of it all. I’ve become a sports fan, which, as it turns out, is not the opposite of a political intellectual. Everybody loves identifying the enemy.

I realized that I had become a soccer fan when I leapt to my feet, propelled not by morality or politics, but swept up in the sheer joy of witnessing the body in glorious motion. This aesthetic pleasure—watching a body dance through time and space—is raw reality upon which nationalism builds its fictional house of cards; this physical joy is also the basis of the economies built upon international sport. But as much as it may be abused by politicians and profiteers, the passion of the sports fan is born of the ecstatic joy of material existence. And in this ecstasy, we forget who we are—and we can forget our enemies, too.

This Sunday, Argentina plays Germany in the World Cup final. And with all due respect to Borges, I’ll have to cheer for Argentina. As a Jew, I have no choice but to root against Germany. But if the match is good enough, then who knows. Perhaps the illusion of “Joseph” himself will dissolve into the ecstatic joy of the beautiful game.

Follow Joseph on Twitter @thejosephrosen.