Edinburgh's Commonwealth Games of Art

Going to a commonwealth art show is a dignified affair—it lacks the chaos of getting on a Venetian water boat while balancing a cappuccino, a map and a wifi-starved smartphone. It just isn’t the same as having sand stuck in your shoes on Miami beach, where everyone is snapping selfies and celebrity spotting through hashtags. It lacks the New York snootiness where the blogerazzi arrives in all black, and it lacks the philosophical loopiness we’d see in conceptual Germany (props to their efficiency, though).

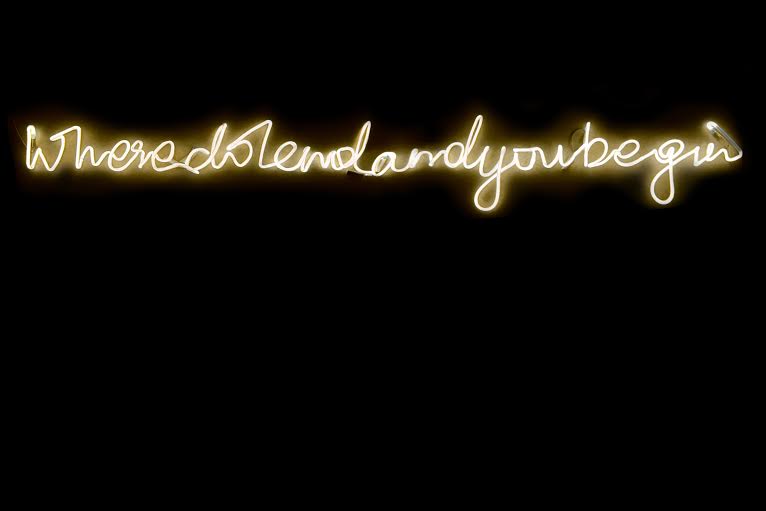

If the Venice Biennale is the art world Olympics, the Edinburgh Art Festival is the Commonwealth Games. Sure, we all know Scotland hosted the Games in Glasgow this year—where they won gold for lawn bowling—but Edinburgh wanted to celebrate by hosting this commonwealth-themed art show. The show wasn’t nationalistic or even straightforward. Where do I end and you begin brings together twenty artists, many born in the 1980s, all from countries that print money with the queen.

A commonwealth art show is filled with rain, inter-exhibition emails from staff, curators and PR people, unnecessary guest lists, roundabout doorways, more flyers than you can count, prim and proper attire (even when the cobblestone hills warn against it), an endless stream of umbrellas, frizzy hair, ocean mist and pleasant chatter. Cooperatively pleasant. This is the story of commonwealth pleasantry. While an Israeli theatre show was cancelled due to pro-Palestine demonstrators over at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, this art scene was taking cabs out to millionaire estates in the countryside for VIP dinner receptions. Without a shred of grit, there were polished pieces of art, glasses of Prosecco, haggis balls drenched in beer batter and press previews. But most importantly, there was art aside from the obvious, even if no one outwardly criticized Queen Elizabeth.

Lost? It seems like the commonwealth history is almost forgotten, or unknown to those who didn’t study it. There are fifty-three commonwealth nations that have been bound with the British Empire since 1931, including South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, India, Jamaica, Kenya and most recently Rwanda, which joined in 2009. But how do you make a commonwealth-based art show that reveals a critical edge? It isn’t full of national presentations like sports, but rather reflections on commonwealth, new perspectives to soak up local knowledge around the complex and mixed emotions surrounding British imperialism, many from the female perspective.

The first thing you see is a self-portrait photo by Johannesburg artist Mary Sibande, who has channelled a fictional character named Sophie, her alter ego. Sibande’s mother and grandmother were both domestic workers, and Sophie is a character based on their past who escapes the drab reality of working hard—she dreams up a fantasy universe where she lives like a queen in her blue-and-white garb. From climbing onto unruly horses to holding up the Superman logo, Sibande’s work has been called a triumph over prejudice, as well as a battle against injustice and ignorance.

What struck me even more were the cartoonish, painted works by New Zealand artist Kushana Bush, which are very Marcel Dzama if you replace the waify hipster aesthetic with some meatier activism. See a topless protest made from green and blue zombie people colliding into one another in a Picasso Blue Period-style, as if parading against a fallen, corroded empire. The voice of the people is always felt in Bush’s work, as if she has created a community newspaper visualized through weird, lurking characters. Except, the voices are fighting on the streets, hollering over one another, bashing into each other, defending one another like a family, a school of thought or a neighbourhood. Although drawn with crisp precision and elegantly-crafted shapes, it’s an argument still becoming, much like the commonwealth theme of the show itself: An argument where not everyone is going to agree.

For those of us who need Wikipedia to connect the dots with commonwealth history, look no further. Emma Rushton and Derek Tyman have built a fabric tent where we can sit inside to watch a documentary. They not only provide the groundwork (constantly citing the history writer Andy Wightman), but the duo invite writers, musicians and other artists to participate through a series of talks around labour, welfare and work.

Not all of it is so entrenched in history—there’s new work around, too. One funny series by New Zealand artist Yvonne Todd shows Ethical Minorities (Vegans), where the photographer has built a community of vegans shot in classic portraits framed with eclectic lighting. Commonwealth vegans, that is.

What about the Canadians in the show? Brian Jungen and Duane Linklater show Modest Livelihood, a silent film touring rural Canada with guns. The star dudes in plaid overcoats and trucker hats venture out on a moose hunt, revealing land rights and common ownership from different cultural perspectives. But the real kicker is in Derek Sullivan’s paste-up piece, a sculpture where he puts posters up on a kiosk to question who is building the Guggenheim in Abu Dhabi. Since being reported that migrant workers from South Asia are building the heavily-boycotted Frank Gehry museum, Sullivan directs us to the Gulf labour website, which is devoted to exposing the harsh working conditions, and in turn, provides an unlikely entranceway to spreading the news the old-school way—through billboard.

What does all this actually say about commonwealth art? They’re looking elsewhere for inspiration and are brought together by their passports and locations. It might have well been an international art show, but it seems as though the curators were searching for cultural trends, burgeoning movements and new voices, even if still becoming.