Putting Montreal on the Map

Layout by Conor Prendergast.

Montreal is a city that has suffered many persistent divisions, whether culturally, linguistically and physically. But it is the physical divides of subjective geography that form the main basis of Tracé/Mapped, a multimedia exhibit that was on display as part of Pop Montreal.

Catherine Gingras, along with collaborators Sandra Breux, Conor Prendergast and Mitz Takahashi, used maps, photography, interviews and video to explore how Montreal’s independent music scene interacts with the city on a spatial level.

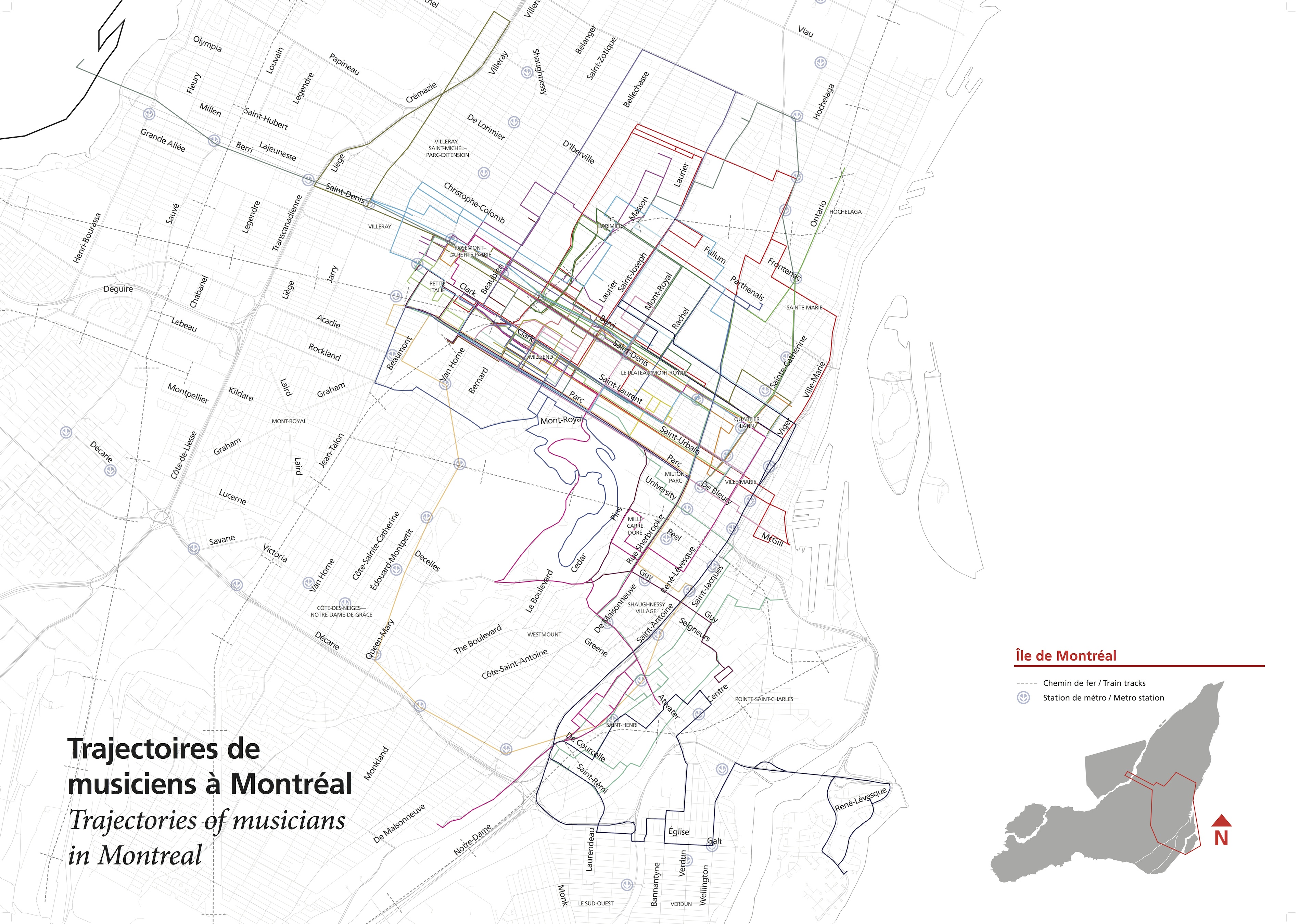

Twenty-five local musicians, including Katie Moore, Marie-Ève Roy of Vulgaires Machins and Matthew Woodley of Plants and Animals, each spent a day with a GPS device that recorded their movements. Their trails were then plotted onto a massive map of Montreal, with each artist’s trajectory in a different colour. The results are striking: colours intersect wildly, tangled up in a vibrant mass between Parc and St. Denis, with lesser strands reaching out to the rest of the city.

The large map is accompanied by two smaller ones denoting performance and recording spaces in the city. These provide a visual contrast, allowing viewers to contextualize the space. While the areas covered are predictably concentrated in the Plateau and the Mile End, other neighbourhoods such as Charlevoix, Villeray and Hochelaga are also well represented.

Gingras says that meeting with the musicians to go over their findings was revealing; many hadn’t considered how short their trajectories were. “It was surprising for most of them to see themselves on a map, to see the size of their own Montreal universe in relation to the whole island,” she says.

In fact, Gingras says that the visual depiction led many participants to want to expound on their relationship with the city. “Some people got very analytical at that stage, offering an interpretation of their experience, and relating it to broader social and identity issues in Montreal,” she says.

The participating musicians also spent the day with a camera, shooting anything they felt was representative of their lives. The resulting photos range from performance shots to intimate home scenes. Several are bare and unembellished pictures of recording studio, sound equipment or CD packaging. Others are more personal: a cat curled up next to a guitar that’s been propped up on a bed; unfinished lyrics scrawled on a piece of paper, words crossed out and replaced.

Many of the photographs are of bridges and underpasses, spatial indicators of division and connection. Gingras has a theory about the persistence of this symbol: many participants exist on the borders between Mile End and Little Italy or Parc-Extension. Many are starting to move away from Mile End—an area she describes as “saturated” with markers of the music scene—in search of cheaper rents north of Van Horne. However, the areas of Little Italy and Parc-Ex don’t have the same cachet of Mile End in terms of the collective identity. Despite the growing number of musicians moving north, she says this change is still “not very readable” in the cultural conception of these neighbourhoods.

The idea for the Tracé/Mapped project began in 2008, when Gingras arrived in Montreal and started going to local shows. As an urban planning student, she was familiar with Montreal both academically and as a consumer of popular media (she cites David Carr’s 2005 New York Times article about Montreal’s music scene as a key element in shaping the way many people think about the city). But at different venues across town, Gingras began to pick up on a “diversity of experiences, in terms of sounds, crowds, and spaces.”

She later expanded on these ideas as a PhD student at the Montreal branch of l’Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique. Her research then moved “outside of the university walls,” with the help of musicians Conor Prendergast and Mitz Takahasi, who contributed to planning the exhibit.

She explains that the participating musicians had a variety of routines: some got in front of the camera, asking friends to film them as they were rehearsing or playing shows; others were strict documentarians. “We sometimes hear that artists are particularly sensitives explorers and observers of our world,” Gingras says. “And in the case of this project it proved to be true.”

The idea of duality is a recurring theme throughout the exhibit, disparate elements that somehow manage to coexist. In addition to the repeating images of bridges and underpasses, many of the musicians interviewed brought up examples of specific cultural and linguistic interactions. Andy White of Tonstartssbandht related the reality of having a Hasidic school across the street from Mile End concert venue La Brique: members of both groups had trouble knowing quite how to act around the other.

Gingras considers Montreal’s linguistic split to be the strongest division in the city, and many of the interviews echo that sentiment. However, Frannie Holder of Random Recipes did observe that there’s now more overlap between the two scenes than previously existed. The exhibit itself is largely bilingual, and it features both anglophone and francophone musicians.

While these questions about the hybrid nature of Montreal were not deliberately introduced during the planning stages of Tracé/Mapped, Gingras says that their emergence is telling about the reality of life in the city.

Follow Maija Kappler on Twitter @Maijakappler.