Architecture in Translation

People often speak of translation when it comes to language. Words are lost and gained in interactions with other places and cultures; they undergo physical transformations when making the journey over place and time. At the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), the concept of translation has also been tied together with architecture in the exhibit Found in Translation, Palladio—Jefferson. The project, a series of photographs by Filippo Romano, examines the relationship between Andrea Palladio and Thomas Jefferson: one considered the most important architect in the Western world, the other one of the most famous presidents of the United States.

The exhibit is a collaboration between Romano and architectural historian (and director of the Palladio Museum) Guido Beltramini. It has been a work in progress since 2012, when Romano began photographing original Palladio buildings in Venice before coming over stateside to focus on Jefferson’s interpretations of Palladio—buildings that include the Virginia State Capitol and part of the University of Virginia’s campus.

The CCA exhibit’s photographs surround the observer, creating an environment that projects one immediately into the world of Palladian architecture. The images themselves focus in on the relationship between the original Andrea Palladio buildings and the new-world Jeffersonian creations, aiming to highlight the “enthusiasm and misunderstanding” that the curators describe as hallmarks to Jefferson’s translation of Palladio’s originals.

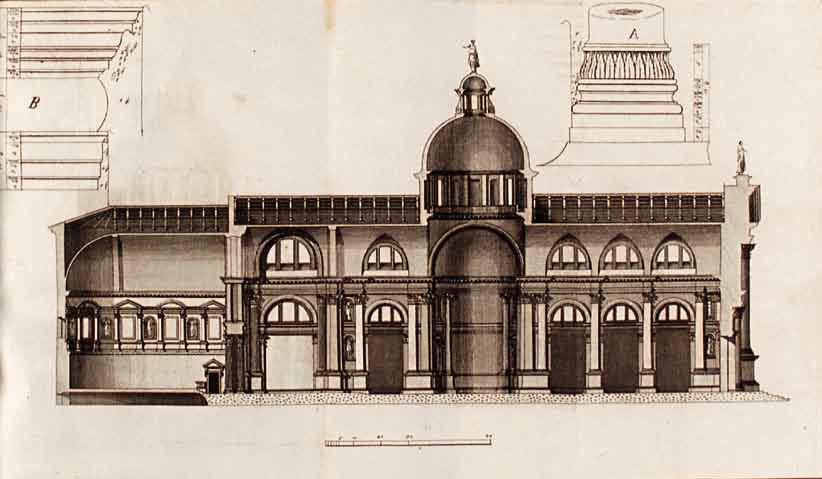

During Jefferson’s time as the US ambassador to France, he became enamoured with Palladio-style buildings and decided on bringing them back home. But as the curators explain, what Jefferson based his buildings on was a copy of the wrong Bible; instead of consulting the original Palladio treatise, Jefferson was examining The Architecture of A. Palladio, an English language translation by an Italian author. The book was translated to English in 1721—almost two hundred years after the original—and offers a great deal of adjustments to the original architecture in order to fit the Baroque style of the day.

The exhibit also points out that despite Jefferson’s deep fascination with Palladio architecture, he never actually visited Palladio buildings while in Europe, instead only relying on his translation of the A. Palladio book. The resulting Jefferson buildings that stand in the US are therefore the final product of interpretations that began in Venice, travelled to England for translation, was found by Jefferson in Paris, before finally settling on the eastern shores of the United States.

Palladio’s original treatise, the Four Books of Architecture (1570), can be found at the CCA exhibit, along with a copy of its first English translation. The exhibit itself is projections of photographs taken by Romano, of both original Palladio buildings and the more recent Jeffersonian copies, across both the US and in Venice. According to the curators, the photographs aim to keep the mystery of whether each building is an original or a copy, leaving the observer in the dark.

One of the more interesting ideas presented by the curators was the importance of capturing the occupants in addition to the buildings. As collaborator Guido Beltramini explains, the owners “belong to the houses,” and are just as important to interpreting the translations of the buildings as the structures themselves.

This also raises interesting conversations within the exhibit about the interplay of architecture and class relations. The original Palladio buildings belonged to owners of Venetian villas. When Jefferson went about recreating the buildings, he was seeking a way to create rural escapes for wealthy landowners. Jefferson saw this architecture as a way of building the new ideal American architectural landscape—something that automatically means a society where the “ideal” is inaccessible for most that reside within it.

This point also allows the exhibit to highlight the way the Jeffersonian buildings played a role in one of the darkest parts of American history: many Palladio-inspired buildings in the US found use as plantations. The curators highlight examples of this Palladio-inspired Jeffersonian architecture in Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained. This observation brings us beyond the mere physicality of the buildings, forcing the observer to consider how architecture relates to power relations and how oppression can be created or sustained by architecture.

Found in Translation presents an interesting way of telling the story of how architecture can be translated and misinterpreted over time. These misinterpretations, it seems, can often yield important results. Perhaps it doesn’t really matter that Jefferson’s reproduction of Palladio was not exact architecturally; if the spirit of the original is transferred over, the loss of some details will not decide whether it is a success of a failure.

Found in Translation: Palladio—Jefferson runs until February 15, 2015, at the Canadian Centre for Architecture.

Follow Jordan Venton-Rublee on Twitter @JVentonRublee.