Hosers and War

From Rhombus Media.

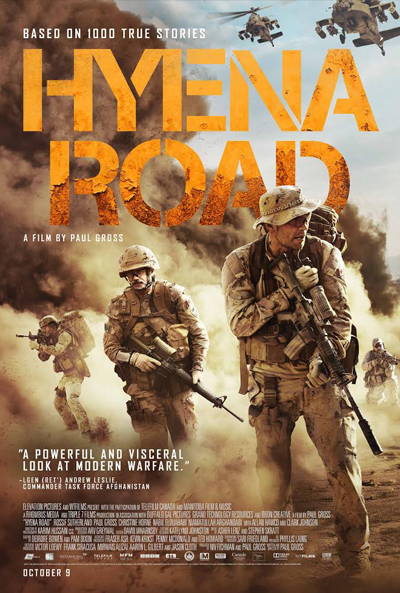

"From Paul Gross, the director of Passchendaele” brags the trailer for Hyena Road, an Afghanistan-set film about Canadian forces during the War on Terror that also happens to be the latest attempt from Canada’s grossly incompetent and largely state-funded culture industry to produce a commercially viable movie.

It may seem understandable that the marketing team behind the film wants to remind viewers of Passchendaele, Gross’ ambitious, patriotic World War I film from 2008, given that most Canadian productions can only dream of reaching its $4.5 million domestic box office gross. But Passchendaele isn’t most Canadian films; it is the most expensive Canadian film ever produced, at a budget of almost $20 million. It was also given a nation-wide release alongside an extensive marketing campaign, which almost never happens for homegrown products.

It is true that the Canadian film market is small, but given that Hotel Transylvania 2 recently earned a little under $5 million at the Canadian box office in just one week, it’s doubtful that Passchendaele can be regarded as any kind of populist Canadian success. Middling box office results could be justified if the film received a warm welcome from critics, but Gross’ awkward combination of old Hollywood melodrama and grisly Saving Private Ryan-style trench warfare earned mostly tepid reviews.

Nevertheless, the powers-that-be (which include Telefilm, a federal government agency that funds Canadian productions, and Cineplex, the omnipresent theatre chain that controls 80 percent of Canada’s movie screens) have decided that Gross shall be the shining beacon of Canadian cinema, and have granted him the opportunity to write, direct and star in Hyena Road.

Hyena Road has that combination of good-natured camaraderie and high-minded seriousness that can make war movies so appealing to teenage boys—the couching of juvenile male bonding within a movie about such vaguely important things as honour, sacrifice and death—but it feels forced, like an assertion that Canada can do this too, even as the network TV-like production aesthetics (possibly due to the fact that some scenes were shot on a soundstage in Winnipeg) suggest otherwise.

As with his previous films, Gross casts himself in a charismatic leadership role. This time, he’s Pete Mitchell, a cynical-but-charming intelligence officer whose goal is to work two local leaders—one a usurious landowner and the other a former mujahideen fighter ominously named “The Ghost” (Niamatullah Arghandabi)—against each other. To this end, he recruits the aid of a sniper unit lead by Ryan Sanders (Rossif Sutherland, son of Donald Sutherland), who was granted shelter by The Ghost during a Taliban ambush. The machinations of the plot are convoluted and they only make sense with a great deal of Gross’ cocky voiceover narration, but the goal of the Canadian forces is to clear a path through Kandahar (the titular “Hyena Road”) through which equipment and food can be transported.

When it comes to the war itself, the film’s attempts at imitating high-powered Hollywood action scenes tends to reveal its own gratuitous nature. When one character has his legs blown off during a firefight, the shots of him crawling toward shelter with two bloody prosthetic stumps is too fake to be realistic and instead feels exploitative. The same goes for a hackneyed romantic subplot involving an unsanctioned romance between the ranks and an unplanned pregnancy on base camp. It is the kind of narrative trick that TV writers pull when an actor is expecting, but in this film it is a transparent attempt at injecting much-needed emotion into an otherwise flat narrative.

If Hyena Road is the Canadian answer to American Sniper, then it feels just like that: a mediocre copy of a well-produced (if morally questionable) original. For the past week or so, the Canadian media has been giving the film a polite response, thoughtfully lowering expectations for audiences by bringing up the film’s relatively small budget. The Globe and Mail will tell you that the film’s $12.5 million budget is “tiny by the standards of any Hollywood war movie.” In reality, Hyena Road cost about as much to make as the $15 million The Hurt Locker, Kathryn Bigelow’s excellent Oscar-winning film about an American bomb disposal unit in Iraq. It’s not a lack of funds or institution support that prevents Gross from making good movies; he’s just not good at making movies.

Just why this big budget war film opportunity was afforded to Gross is a question that also bothers filmmaker Guy Maddin in his bizarro Hyena Road “making-of” documentary, Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton (directed by Maddin, Evan Johnson and Galen Johnson). Maddin, the critical darling behind weird, low-budget gems such as My Winnipeg and the recent The Forbidden Room, premiered the film on a flat-screen television at the front of the TIFF Bell Lightbox during last month’s Toronto International Film Festival—the day after Hyena Road premiered at a swanky gala at Roy Thomson Hall.

Maddin’s pseudo-documentary is framed by scenes of the eccentric filmmaker wandering around the Hyena Road set in Jordan, gawking at the decadent food options available from craft services via a not-at-all reliable voiceover (“Where I’ve always relied on Lobster Garden coupons scrounged from garbage cans, Paul’s catering features rack of lamb and fresh Nova Scotia oysters.”). As he laments his own financial situation (“flat broke”), Maddin admits that he is only making this doc because he wants some of that Paul Gross money for himself.

Later on in the film, Maddin ponders whether or not war films can invoke the imagery of war without inadvertently glorifying it as well: “all the pomp and ceremony of real war, but without real death.” As if to emphasize his point, Maddin closes his film by recutting Hyena Road’s climactic stand-off—involving two feuding Afghani leaders and a dismembered head—as if it were a Sergio Leone Western, replete with a janky, whistling score and the sounds of neighing horses and creaking saloon doors.

The implication is that for all its contemplation about the moral complexities of war, Hyena Road is about as serious a work of art as your average Hollywood Western and that Gross is more concerned with breaking through in the Canadian market than he is in contemplating the War on Terror. Gross is, after all, that most Canadian kind of phenomena: a populist artist without any popularity. And so he seems to be eternally searching for that key to the hearts and minds of Canadian consumers.

More than any other filmmaker within these borders, Gross has taken it upon himself to define Canadian identity through film. In his first film, Men With Brooms, he tackled Canadiana by taking on curling, a sport so parochial and inoffensive that only a Canadian would try to claim it as part of his national identity. With Passchendaele, he gave an epic sweep to a battle that social studies teachers have bragged about to their students for decades. In each film, he seems to find the essence of “Canadianness” within the fraternal bonds between his characters, whether they’re a bunch of hosers playing ice sports or a close-knit sniper unit fighting in Afghanistan.

Perhaps this is Gross’ fate, doomed forever to define Canada after being cast as a good-natured Mountie in the cheesy 1990s TV series Due South. As the ever-polite Constable Benton Fraser, Gross donned the iconic RCMP uniform while solving crimes out of the Canadian consulate in Chicago, accompanied by his loyal dog, Diefenbaker. Despite his charms, Fraser is a rather unfortunate symbol of Canadian identity: a man who prides himself on being slightly better than Americans but still craves their approval.

In the book Imagined Communities, political scientist and historian Benedict Anderson defines a nation as an “imagined political community,” stemming from a “deep horizontal comradeship” which justifies any given nation’s political sovereignty. This imagined community is the “fraternité" in the French national motto “Liberté, égalité, fraternité.” It is the part of the saying that doesn’t just reference political ideals, but defines the exclusive club that gets to enjoy those ideals. The idea of a national community can bring people together on the basis of a shared language, culture or ethnicity, but it can also be used to divide people and ostracize those that don’t qualify for membership.

Judging by Gross’ film, Canada seems to be a collection of simple-minded hoser-bros who bond over sports and war, but also stand up for what’s right. Women are sidelined, while First Nations and people of colour are included when they share in that distinctly Canadian camaraderie that Gross builds between his characters, but there’s no big-city multiculturalism in sight.

The idea of the nation as a political entity, contrary to the beliefs of patriots everywhere, is quite recent. According to Anderson, it originates from the spread of print publications in the American colonies, which allowed American-born “creoles”—first in the thirteen colonies and later in Spanish South America—to conceive of themselves as distinct political entities and eventually wage revolutionary wars to free themselves from their colonial yokes. The nation is thus built on those shared histories of oppression and subsequent liberation.

Despite locating the origins of nationalism in the Americas, Anderson barely mentions Canada, except to mention the United States failure to “absorb” us. The way he tosses off the words “English-speaking Canada” almost makes sound like the British Virgin Islands or one of those other tiny colonies that got left behind while the rest of the New World was stockpiling arms and preparing to liberate itself.

Whatever our qualities as a country or a state, Canada is a pretty shitty nation. Quebec, with its rowdy talk show circuit, profitable film industry and its shared love of Robert Charlebois, has more of the cultural qualities of a nation than Canada has ever had, which might explain why many there would rather form their own country than participate in ours.

The rest of us are spread so far apart that any idea of a community is limited to the idea of free healthcare and strong gun control. Even the beer-swilling hoser stereotypes of the Bob and Doug McKenzie days are increasingly out of touch in this age of globalization and multiculturalism. We have no founding myth upon which our nation was built; no war of independence nor a glorious empire to look back on. Instead, Canada just kind of stayed a colony until that wasn’t popular anymore. Now we are a nation by default.

A shared popular culture is common among nations, but demonstrably more English-speaking Canadians feel at home watching NCIS than Murdoch Mysteries. That’s not to say that successful Canadian pop culture doesn’t exist, but instances are few and far between and usually referred to as the Trailer Park Boys. Yet this is the Canada to which Paul Gross makes his appeal with Hyena Road: a Canada that mildly prefers hockey over other sports, a Canada that’s brought together in outrage over the foreign ownership of Tim Hortons, a Canada that bonds over superficial similarities rather than deep ones.

Both hockey and Tim Hortons make an appearance in Hyena Road, despite the warm climate of its Afghani setting. They both exist on the Canadian military base in Kandahar, where troops and contractors can patronize the local Tim’s (which is based on a real location) and play pickup hockey games on a concrete rink. It’s a kind of Canada-outside-of-Canada, a sanctuary from the cruelty of war-torn Afghanistan. Gross’ voiceover description of the base within the film, or of the Canadian military presence in Afghanistan in general, borders on the superlative. The inclusion of Tim Hortons and hockey is important within those voiceovers, because otherwise there’s nothing distinctly Canadian about their presence.

When Gross’ deep, commanding voice combines with some suitably fast-paced music and a montage of military-themed footage, Hyena Road sometimes resembles those stylish Canadian Armed Forces advertisements that play before movies. The film itself would be propagandistic if Pete Mitchell, the cynical intelligence officer played by Gross himself, didn’t directly challenge the Canadian role in that country, describing it as “unwinnable” and bluntly explaining the knotty moral and logistical complications in the way of a Western victory in the area.

Perhaps we should be glad that Gross isn’t making wholesale propaganda on the public dime, but that may be the most frustrating thing about the movie. It’s a broadly patriotic, jingoistic film about the Canadian war effort, yet the guy who made it is too self-conscious to follow through on that premise. Instead, Hyena Road is an intellectually and aesthetically confused mess, which wants to celebrate the sacrifice of Canadian soldiers but remain ambivalent about the reasons for those sacrifices.

Hyena Road is too thoughtful to be good propaganda, but it’s too dumb to just be a good film. In the end, we’re left with no reason to celebrate these soldiers, other than that they are Canadian. And we are left with not much reason to watch this film, other than that it is Canadian. And as Gross’ previous, clumsy attempts at untangling Canadian identity have already shown, that may not be much of a reason at all.