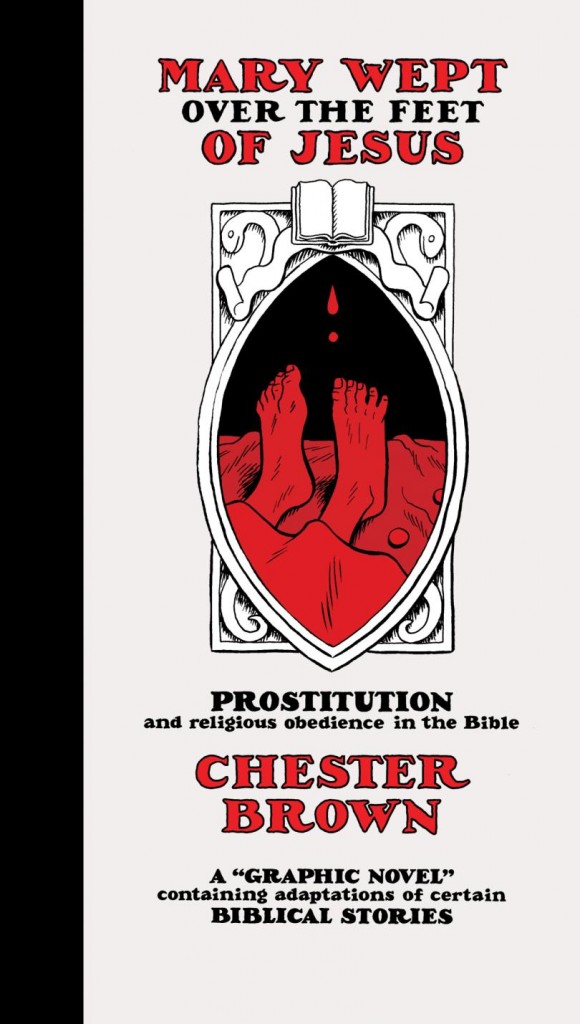

Bawdy Bible Stories: On Chester Brown’s Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus

In Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus (Drawn and Quarterly), Chester Brown seeks the roots of the Judeo-Christian view on sex work through his depiction and interpretation of the Biblical stories of Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, Bathsheba, Mary of Bethany and, finally, Jesus’s mother, Mary.

In the chapter entitled “Matthew,” Brown depicts Matthew sitting down to write his gospel decades after Jesus has been crucified. “What should I do?” Matthew asks himself. “All the evidence indicates that Jesus’s mother was a whore. Jesus himself said so. But many of my fellow Christians are against prostitution, and they don’t want to hear the truth.” Brown shows Matthew going for a walk. On his walk, he meets a girl named Tamar who offers him her services as a sex worker; Matthew declines, but he’s had a breakthrough: he’ll invent a genealogy for Jesus, focusing on his matrilineage, that includes “whores” and “whorish” women. His goal, according to Brown, is to intimate sex work while escaping the censors.

Mary Wept also tells the stories of Cain and Abel, the Talents, and the Prodigal Son, which all study religious obedience—in fact, he argues that the stories show that God respects people who disobey his instructions—and once again almost always includes the topic of prostitution in some way. Brown’s use of often-explicit illustrations and blunt, humorous dialogue presents these familiar stories in a modern light. In the story of Tamar, a man named Judah negotiates with a sex worker—Tamar in disguise—to hire her for the night. “I’d like to lie with you,” says Judah, and he and Tamar begin to haggle. “What will you give me?” she asks; when he suggests a sheep, she says she’d prefer a goat. While this kind of bartering may have been normal many moons ago, it seems comical today. This interaction allows us to understand that sex was just another commodity then, which is drastically different from the perception many have of prostitution today.

Brown argues that while many of the writers of the Hebrew Bible frowned upon—but tolerated—prostitution. He makes the claim that the New Testament writer Paul disapproved so strongly that Christianity struck a solid position on the matter: prostitution is sinful. “Some of you may feel that the apparent approval of prostitution contradicts Jesus’s teachings,” Brown writes, “but Jesus never said that it’s wrong to sell sex or pay for it. It was Paul.”

With the spread of the religion, writes Brown, came the spread of “whorephobia,” and laws against prostitution across the globe. Non-Christians who believe that their disapproval of sex work is undergirded by rational, secular reasons are “fooling themselves.”

Brown has a personal connection with prostitution; he says that he has slept exclusively with one sex worker for the past eleven years. In the afterword to Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus, Brown asserts that he doesn’t see anything morally wrong with the fact that she has sex with him for money, or that he pays her for sex.

Mary Wept grapples with the origins of modern laws and taboos against sex work; in many respects, it’s almost an extension of his last graphic novel, Paying for It, in which he described his experiences with sex workers, and called for the decriminalization and social normalization of the profession. In Paying for It, Brown depicts how he’s navigated being a John with sex workers and with friends, not all of whom accept or embrace his choices. The taboos that Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus seeks to dismantle are the very same that have made Brown’s life difficult for some of his loved ones to understand.